FEATURES

(The war years)

Excerpted from Chosen Ground: The Clara Motwani Saga by Goolbai Gunasekara

When war broke out in 1939 its reverberations were worldwide, of course. Not for nothing was it referred to as World War II. Yet the widening ripples of the dreadful conflict barely reached our shores in Sri Lanka. The British Empire had weathered World War I from 1914-18, and so there seemed to be no good reason as to why we should not expect it to do likewise in 1939. Our confidence in the invincibility of the British Empire was such that even the declaration of war. seemed a far away affair which the British would handle with their customary elan, ensuring that the colonies and dominions were protected at all times.

Wiser local brains saw through the facade of invincibility. They realized quite early in the day that if this island were to be the focus of an enemy attack there was no possible way Sri Lanka (then Ceylon) could be defended. The British knew it and local leaders of the political community knew it — but the population at large did not know it, and thus worry was at a minimum.

It was not OUR war after all. The British ruled us, and the people of Ceylon felt that our rulers were well served by having total access to all our resources — especially our rubber, at prices set in Britain. Had the owners of the island’s rubber estates been allowed to sell their produce in the open market at the time, Sri Lanka might not be in the economic doldrums of today. Similarly, all the island’s assets were regarded as Britain’s by right of conquest, and so Ceylonese felt they had done more than their bit as far as the war was concerned. They settled down to see it through.

The question of ‘evacuation’ trembled in the air. Until such time as schools could be transferred up to the hills, schoolchildren in the coastal areas were taught air raid drill. This provided an exciting little interlude in our daily life. It worked thus. A siren would sound that would be heard all over Colombo. At that signal, school kids dived under their desks, or lay flat in the corridors until the all-clear sounded. Sand bags were piled up on roadsides, and even in schools, giving us a thoroughly deceptive feeling of security. As far as school girls were concerned, it made for a welcome break in the monotony of school life.

Eventually, of course, the Principals of the big Colombo schools began making preparations for an exodus up-country. Schools were soon divided to form an ‘Up-country Branch’ and a ‘Colombo Branch’.

The Royal College buildings in Colombo were taken over by the British Government and so the school transferred to a new location at “Glendale” in Bandarawela. St.Thomas’ College, which already had a branch at Gurutalawa, also went to Getambe. Bishopians trotted off to Kandy, and sited themselves at “Fernhill”. Further up was Ladies’ College in “Uplands”, while the students of Bishop’s College and Ladies’ College who were left behind in Colombo, joined up as the “Lake School” – probably the only time these two rival schools have ever been so close.

Somewhere along the way however, our complacency received a little jolt. Singapore fell and the Japanese were too close for comfort. Schools that could afford a quicker evacuation began moving up to the hills. Visakha soon began this process itself. Under the Principals of these schools (mostly foreigners) work and studies went on without missing a beat. A holiday atmosphere may have been noticeable but it did not penetrate into the classroom agendas. My own mother, as Principal of Visakha, had to divide her time between the Colombo branch and the Bandarawela branch. I presume that all the Principals shuttled up and down in a similar manner. Certainly the train journeys up and down were comfortable beyond belief. Snowy white sheets and fluffy pillows were laid on berths in the First Class carriages, which made the journey totally delightful.

Mother eventually used a personal friendship with Mr. D.G.K. Jayakody who had a large home, “Chandragiri” in the hills of Bandarawela. It was rented by Visakha for the new branch school. Temporary classrooms were built while the main house was used for the boarding. One of Mr. Jayakodys granddaughters, Ramya, remains my close friend to this day and her granddaughter, Saveeta, is one of my pupils at the Asian International School at the moment. Another instance of the circle of life!

Classes began. Mrs. Susan George Pulimood (subsequently Principal of Visakha), and Mrs. Chandra Godakumbure, wife of the later Archaeological Commissioner, were among the numerous excellent teachers who went up to Bandarawela. Mother ran both schools in Colombo and Bandarawela on a shuttle system which seemed to work well enough. She had a great time, enjoying the slightly unorthodox atmosphere. Small classes gave her time to get to know every girl intimately — whether the girls enjoyed such close personal attention was another matter. Mother concerned herself with neat cupboards, clean clothes, hairstyles, diet, personal hygiene, exercise and everything else, not really a Principal’s usual business.

It would be correct to say that these mountain schools, so small in number and in size, functioned as happy families. There were compulsory religious activities, of course. The Bandarawela temples and churches never had so many adherents as they did during the war years.

For excitement and entertainment there were the movies. Whatever Britain was doing on the various war fronts, her colonies received regular inputs from the film studios. Two changes a week was the order of the day. Mother would graciously allow her Visakhians to walk into town to see the latest Greer Garson or Ingrid Bergman offerings (among others) on the silver screen. We thrilled to ‘Dangerous Moonlight’, `Mrs. Miniver’, and other movies of high romance. Films that starred Shirley Temple and Margaret O’Brien were considered suitable for us juniors. To this day I remember the hair of Dr.Thelma Gunawardena (now retired Director of National Museums), done in Shirley Temple ringlets.

In Diyatalawa, three or four miles from Bandarawela, there were two theatres which catered to the servicemen and the general public. If the teachers at Visakha felt particularly adventurous, they would walk the distance and back just to see a film that had been highly publicized. Older girls were allowed to accompany them, and there were some touching incidents.

One of the movies had taken an unusually long time to end, and it was dusk when the Visakha contingent finally emerged from the cinema to begin the long walk home. It was a time when violence was minimal. The whole island was safe, safe, safe. Whatever fear the group might have felt was mainly because of animals that may have unexpectedly run across the road. Buses did not run so late and in any case there was petrol rationing.

Cautiously, the Visakhians decided to set off. Sri Lankan voices are not necessarily soft, and a group of British officers soon caught on that this was a bunch of jittery natives. One of the senior officers approached the group. “I can have you escorted back to Bandarawela,” he said, and proceeded to send two cadets along with the nervous ladies . Naturally they got chatting on the way, and the two young soldiers told the Visakhian group that they were the first Ceylonese who had talked to them, apart from the servants they employed.

Seeing the Visakhians hiking up the Visakha hill with two young British soldiers as escorts almost gave Mother a heart attack. She had visions of angry, tradition-oriented parents getting to hear that their offspring had actually arranged to meet those dastardly British soldiers, whose intentions just had to be questionable, if not downright dangerous. She eventually recovered enough to send their C.O. a nice note of thanks, but it was a long, long time before Visakhians undertook that walk to Diyatalawa to see a film, however marvelous it might be.

Then there were the paper chases, otherwise known as the ‘Hares and Hounds’. These were dear to Mother’s heart. Not only were her girls learning the art of simple tracking, but they were also breathing in all that marvelous mountain air for which Bandarawela was justly famous. Writing about the ‘Bandarawela Experience’, author Manel Ratnatunga has this to say:

“But it was only the evacuation of the school to Bandarawela during the war years that brought me close to Mrs. Clara Motwani, our Principal. To all of us in those makeshift classrooms on the hills of Bandarawela, fragrant with eucalyptus and pine, she made us realize that a school could maintain high standards of learning and discipline even in makeshift buildings.

“In the dwindled school the communication gap between ‘the awesome American Principal’ and staff and students was bridged in a manner that would not have been possible in the large and impersonal Colombo buildings. With wisdom and good leadership, Mrs. Motwani altered her style to fit the countryside and keep her homesick brood well and happy.

“So there we were accompanying her on three-mile walks which had us running to keep up with her strong, long strides; visiting the rickety old cinema house atop some garage (she sometimes included the domestics, who looked askance each time there was a kiss on the screen); hitching train rides on excursions to neighbouring townships; trekking cross country over hill and dale. She was always with us, the least exhausted, and perhaps because of that day and age we never crossed the ‘Maginot line’ of respect for the Principal or our teachers. Memories of euphoria.

“For religious instruction, with no Narada Thero of Vajiraramaya Temple on call, Mrs. Motwani’s Visakhians turned to the Czechoslovakian monk, Rev. Nyanasatta, from a lonely hermitage, as he spoke English, rather than to the local monks who sometimes didn’t.”

But alas! My happy days of Dr. Ratnavale’s advised freedom were coming to an end. I was transferred to the Froebel School, also in Bandarawela, which catered mostly to foreign children. Many of the students in this school had fathers in the army and so regular bulletins were reaching us eight-year-olds from other authoritative eight-year-olds. The boys’ favourite game at Froebel was called “Bombers and Blackouts”. We girls were nurses and other unexciting helpers. My friend Suriya (Doreen Wickremasinghe’s daughter) went up to Froebel before I got there but her unusually high IQ placed her in a class or two above me.

Many wealthy Colombo citizens maintained lovely holiday homes in the hill country. The British began commandeering the best unoccupied ones on a year-round basis, for the use of their Army Officers. There was a large Army Cantonment in Diyatalawa, just three. miles from Bandarawela. Wishing to keep the British officers from taking over her upcountry bungalow, Mrs. C.V. Dias, who knew

Mother, asked if she would like to occupy “Suramya’, her beautifully appointed house, which stood on the hill the same as “Chandragiri”.

Mother was delighted and so were Su and I, for “Suramya” was delightfully luxurious. Just below “Suramya” was the holiday home of S.J.E Dias Bandaranaike and his wife Esther. They had three daughters, all of whom now entered Visakha for the duration of the war, as their old school, Bishop’s, was too far away.

Aunty Esther was an Indian, and was not only lovely to look at but also had a formidable brain … something all her three daughters inherited. The eldest, Gwen, became Principal of Bishop’s College. Sonia, who went to Cambridge for her medical degree, practices medicine in Suffolk, while Yasmine, the youngest, is Emeritus Professor of English Literature at Macquarie University in New South Wales, and has been awarded the Order of Australia for services to literature and education.

Aunty Esther had known Mother earlier, but that Bandarawela neighbourliness cemented a strong friendship. Her youngest daughter, Yasmine, became my friend and still is. Yasmine, her sisters, and I would all play Monopoly on the huge Bandaranaike antique beds which served as divans, or comfortably read books together during my holidays from Froebel. These are the memories I have of Bandarawela. These and many others.

The ‘in’ shop at Bandarawela during the war (in fact the only well-stocked one) was a branch of Colombo’s `Millers’. It pretty much catered to everyone’s needs. Our hair was cut by an elderly barber at the Bandarawela Hotel, whose clientele ranged from age three to 83. Hair styles were unheard of. We read of rationing in England, but in Ceylon no one was actually losing weight because of any constraints. In short, food was available. A locally made chocolate, ‘Barbers’, was substituted for Cadbury’s and Nestle’s – but we managed.

On one never-to-be-forgotten day, a bomb (or bombs) fell in Colombo. The girls at Visakha were in a tizzy. No work was done at all. Visakhians tried frantically to call their homes but as each call was a trunk call (which took about two hours to connect) there was little communication between them and their parents. As I remember it, I don’t think anyone was actually killed by those few bombs … but I am open to correction. Certainly, Ceylon had it good during the war.

Colombo, meanwhile, was rapidly becoming a ghost town. On the gates of half the residences of the city there were signs reading “To Let”. A house could be leased for Rs. 100/- a month, and even that was considered a luxury rental.

Back in India my father, nervous about the vulnerability of the island, soon carted his family back to the Nilgiri Hills. The story of how this came about is related later. My sister and I finished the War as pupils at the convent in Ootacamund in India, where we managed, again, to ignore the European conflict as both Father and the Indian newspapers were far more concerned with the doings of Mahatma Gandhi, Nehru and the Indian Congress.

The unorthodox schooling arranged for the Bandarawela Viskhians during the war years has resulted in many tales being told. Dr. Geeta Jayalath remembers Mother tucking her into bed. She was just 10-years old. Incidentally, Geeta was one of the first Visakhians to qualify as a doctor after Mrs. Pulimood introduced the Science stream into Visakha when she succeeded Mother as Principal. Her sister Ishwari Corea, whose name is synonymous with the Public Library, remembers that Visakha-in-the-hills had no boundary walls. Students knew they should not stray out of the general periphery of the school.

One Sunday, Ishwari and a few like-minded dare-devils were merrily coasting up and down the school hill when to their dismay they ran smack into Mother, who, running true to form, was checking up on het boarders when they least expected it. Reversing themselves they sheepishly followed her up the hill. Her ‘punishment’, if it could be called that, was typical. She always explained WHY she was handing out a punishment. She did so now.

“Ishwari,” she said, “I am quite aware you were in no danger, but let us just suppose that your parents had decided to visit you, and that I was unable to find you. What could I have possibly said to them?”

A highly popular `correction’ was being asked to wait over at mealtimes for everyone else to finish. Verona Ranasinghe, one of the stricter Prefects, was constantly on the alert for little miscreants. She reported them to Mother, who tried to make the punishment fit the crime.

What Mother did not know about this particular crime-deterrent was, that the late diners got far more than those who had gone before. There was always plenty of food left over, and the extra banana, the extra slice of pineapple, even any extra caramel pudding was theirs for the asking. Mother had no idea that waiting 15 minutes for dinner was no great hardship, and she always handed out her corrective measures reluctantly. Secretly jubilant, Ishwari and her partners in crime looked so upset that Mother, who hated any disciplinary action connected with food, revoked her order.

“Never mind,” she told the little hypocrites, “I’m sure that my talk with you will of itself be enough to halt any unscheduled walks in future.”

“Oh, thank you Mrs. Motwani,” they chorused, as all that extra food evaporated before their very eyes.

Mother frequently mentioned the livelier (and therefore better remembered) girls in the boarding. Yasoma Rupasinghe was one of these, and Vinitha de Silva (now Dr. de Silva) was another.

“Her eyes literally sparkled,” Mother would say. Then there was pretty Indra de Silva, mother of the famous cricketing Wettamunis, who closely resembled the film star, Deanna Durbin. She was at that time a highly popular actress, and, was reputably Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s (president of the USA) favourite screen idol.

The Hewavitharna girls, Manel, Rani, Sita, Manthri, Kaushalya and Indira were day scholars, but they joined in most of the hostel programs. Manel was Mother’s star pupil in English. It was a talent that flowered, for Manel has become a well-known writer and is the author of many books, one of which was short listed for the Gratiaen Award.

Dhameswari Karunaratne’s parents also lived on the Visakha hill and this little academic genius went on to become the Vice Principal of Visakha after a brilliant scholastic career. She would get a near 100% in every subject, which was terribly discouraging to her classmates who, try as they might, could not retch such perfection.

There were even two boys amidst all these girls and they certainly lent colour, if not spice, to this all-girl establishment. There was no doubt in anyone’s minds that this early exposure to all female company gave these boys a head start in life, for they have both been highly successful in their chosen fields. Channa Gunasekara went on to become Sri Lanka’s Captain of cricket while Singha Basnayake ended a brilliant scholastic career working for the UNO. Lest Visakha takes all the credit I must add that both young men returned to Royal College from whence they had sprung.

There was a personal outcome of the Bandarawela days which concerned Mrs. Pulimood and myself Mrs Pulimood was the only Christian in Visakha at that time. If I happened to be home on vacation from Froebel, Mother sent me along with Mrs. Pulimood to keep her company on the walk to Church and also to fulfil Mother’s belief that all religions are worthy of being studied. As a Syrian Christian, Mrs Pulimood would explain to me that hers was the oldest organized Christian Church, dating back as it did from the arrival of St Thomas (the doubting Thomas of the Gospels) in India. I wonder if she ever realized that my subsequent deeper involvement with Christianity was the result of those first seeds sown by a brilliant teacher.

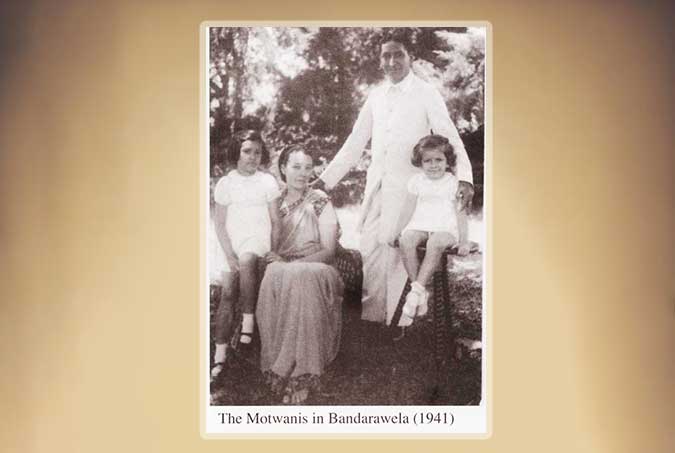

Father came to Bandarawela only once. We still went to India for holidays but for the greater part of the War, Father was on tour. He stayed put long enough to lecture for two years at the Tata Institute of Social Sciences in Bombay, but he kept telling Mother that she should join him in India as Ceylon’s defences were minimal. Mother would never leave Visakha until Father forced her hand as related elsewhere.

For the present, Mother continued her life as a commuting Principal. Whenever she was down in Colombo she either stayed with Dr. and Mrs. E.M. Wijerama, her close friends, or else with Dr. and Mrs. Blok whose daughter Winifred had been a pupil at Visakha. Winifred was a talented pianist. As a pianist herself, Mother loved listening to Winifred’s playing. It heightened the enjoyment of these rare social evenings of warm hospitality spent in the company of gracious friends.