FEATURES

Priceless stolen property

by Kumar David

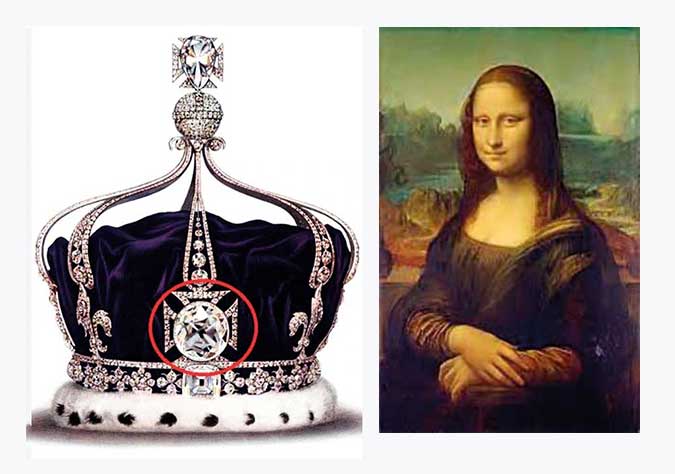

Where the Koh-i-Noor diamond was found is impossible to tell because that was a long time, perhaps more than five centuries ago. It is an alluvial diamond meaning it was found in shifting sands in a location that had once been a river bed. It passed through the hands of Nadir Shah (from whom we have the English word ‘nadir’) who sacked Delhi four times between 1738 and 1767, inflicting untold suffering on the city. On one occasion he took the diamond back to Persia as war bounty where it adorned the Peacock Throne. It remained there until Nadir was assassinated in a palace coup. Thereafter the diamond travelled to Afghanistan, and back briefly into the possession of an Indian Maharaja Duleep Singh. Then only 11 years old and scarcely able to comprehend what he was doing, the kid Duleep gifted his kingdom to the East India Company and the Koh-i-Noor to Queen Victoria. It reached England in 1850.

However, King Chuck III’s consort Camilla Parker Bowles, will not wear the Kohinoor for the coronation on May 6 because of protests in India about misusing the stolen diamond. She will instead wear Queen Mary’s crown made in 1911 for Mary of Teck which contains a crystal replica of the Koh-i-Noor.

The story of the Mona Lisa is hardly less ignoble. It was looted by Napoleon together with about six hundred art treasures from all over Europe. Napoleonic looting was a series of confiscations of precious objects by the French from Italy, Spain, Portugal, the Low Countries, and Central Europe. Looting began around 1794 and continued till Waterloo. An immense quantity of art was acquired, destroyed, or lost through treaties, public auctions, and unsanctioned seizures. The French justified this as both a right of conquest and an advancement of public education and Enlightenment ideals. Many works were given back but many remained in Paris due to resistance to return within France. The Mona Lisa, the world’s most famous portrait, will remain firmly in the Louvre until at least WW-III.

What apart from their legacy as stolen treasure, do the Koh-i-Noor and the Mona Lisa have in common? Valuation. What are they worth? People call them priceless but there is one marker – insurance charges. The cost of insurance is a rough marker. It is a defective pointer because in is perturbed by markets and by recent events such as trends in the theft of art works. Both the diamond and the Mona Lisa have been insured at between US$ 500 million and US$ 800 million at various times. But that doesn’t work. If you owned a Manhattan property valued at eight million dollars nobody will give you the Koh-i-Noor or the Mona Lisa in exchange for 100 of these flats. Another comparison is that Apple, the largest company in the world, has a global stock capitalisation of about $ I trillion. Think of it, the Koh-i-Noor and the Mona Lisa are each worth a significant proportion of the global stock capitalisation of the world’s largest corporation. Hmm, just for a lump of colourless carbon or a painted piece of canvass!

It is morally correct, and reflects basic property laws, that stolen or looted property should be returned to its rightful owner. Here is an abbreviated version of a report in the Guardian newspaper. “Cultural objects belong together with the cultures that created them; these objects are a crucial part of contemporary cultural and political identity. Six artefacts looted by British troops 125 years ago from Benin City, in what is now Nigeria, are being repatriated to their place of origin, there is pressure on European museums to follow suit. Objects, including two 16th-century Benin bronze plaques ransacked from the royal palace, were handed to the director general of Nigeria’s National Commission for Museums and Monuments who said he hoped other museums holding looted artefacts from Benin City would be encouraged to do the same. In particular, he believed an agreement could soon be reached with the British Museum, the national cultural flagship that holds 900 objects, the largest collection in the world”.

Germany handed over two Benin bronzes and put more than 1,000 other items from its museums’ collections into Nigeria’s ownership. “It was wrong to take the bronzes and it was wrong to keep them. This is the beginning to right the wrongs,” said the German foreign minister. In a separate dispute the Greek prime minister raised the repatriation of the Parthenon marbles – one of the most important collections of classical art in existence – at a meeting with King Charles at Windsor Castle. The marbles have been on display at the British Museum since 1892, after Lord Elgin had them stripped from the Parthenon and shipped to Britain”.

The British Museum’s (BM) collection has grown since 1753 when it acquired the founding collection from Sir Hans Sloane. Here is the story of some famous pieces of looted art.

Benin Bronzes are in many European museums

Parthenon Marbles proudly displayed at the BM

The Rosetta Stone which is in the BM enabled researchers to decipher the ancient Egyptian script and understand the cultures and history of ancient Egypt.

Tipu’s Tiger: The tiger was made for Tipu Sultan, ruler of the Kingdom of Mysore in India in the late 18th century. I don’t know where it is at present

Maori heads, decapitated, dried, and tattooed Maori heads are on display at various European museums, including the BM. They look gruesome.

Drawings of Saartjie ‘Sarah’ Baartman. Saartjie “Sarah” Baartman was a Khoikhoi woman who was taken from South Africa to London and exhibited as a freak show attraction in the 19th century. She was given the derogatory name “Hottentot Venus,” using a term for the indigenous Khoikhoi people. When Baartman was sixteen, her husband was murdered by Dutch colonists, and she was sold into slavery. In 1810, Baartman was said to have signed a contract with a British physician who was her master’s friend, and was taken to Europe to be paraded around for her large bottom. She became the subject of scientific interest and racialized eroticism. Even after her death in 1815, Baartman’s remains were displayed at a museum in Paris for decades. In 2002 President Mandela successfully negotiated for her remains to be returned to South Africa and given a proper burial.

FEATURES

The Gunner Platoon at Weerawila Down South in 1971 – combating the JVP Insurgency

A personal story as recalled by Capt F.R.A.B. Musafer 4th Regt SLA (Retd)

Background

The year 1971 was ushered in with a very pleasing political utterance to the public that the Army did not need guns but needed plowshares – agricultural machinery and tools to support the food drive. It was at a time when the Army, an essentially peacetime operation entrusted with the internal security of the country, had turned its attention to assist with national paddy cultivation and other agricultural projects countrywide.

With an estimated strength of around 8,000, the army was not a well equipped force by any means. It was frugal in outlook and dependent on existing resources. The military hardware was virtually hand-me-downs of the British Army and of World War II vintage. The bulk of the small arms in use were the old .303 Enfield rifles the rest were made up of light machine gun (LMG), sten gun (SMC) and the sterling sub machine gun (SMG) and the .38 Smith and Wesson pistols. The infantry units were being re-equipped with the 7.62 mm self loading rifle (SLR’s), a sophisticated and automated weapon in use by the British Army.

The Armoured corp was the glamour regiment equipped with Ferret scout cars and Daimler armoured cars that were impressive and operational. The Artillery regiment had four 76mm mountain guns gifted by Yugoslavia that were also operational, though the need for their use was considered far fetched. The regiment also had a battery of 3.7 inch anti-aircraft guns used for ceremonial gun salutes and a battery of 40mm Bofor anti-aircraft guns that were obsolete.

The army was subjected to a fair share of austerity as was the rest of the country; petrol was issued on a quota basis, the use of ammunition for training strictly monitored and some basic military essentials hard to come by.

The State of the Nation

In May 1970 the Sri Lanka Freedom Party under the leadership of Mrs Sirima Bandaranaike was swept into power with an overwhelming majority with the help of the left parties with whom the SLFP ran as a United Front (UF). The JVP, though not a political party, gave its support to the coalition as it was socialist in outlook and totally opposed to the capitalist ideologies of the United National Party.

The victory instilled in the people a new hope and they labeled it as the “Apey Anduwa” (Our Government) hoping that there would be an improvement to their lives. However as time progressed the hardships faced by the people did not appear to improve as the economic situation only worsened. Strict import and exchange control regulations were in place. Basic items such as bread, sugar, dhal and infant milk were rationed. Food, clothing and vegetables were expensive if not scarce. The transport of rice and chillies was prohibited. The cost of living had sky rocketed and the people feeling its effects were a disillusioned lot .

The Prelude

At the beginning of 1971 there were instances of bombs accidentally going off in various parts of the country predominantly in the Kegalle and Kandy districts. The roof of one of the buildings in the Peradeniya campus was damaged as a result of one of these explosions. Mixed signals were beginning to emerge that there was trouble brewing and the JVP, often dubbed the Che Guevara Movement, was behind the plans to initiate an armed insurrection. Intelligence gathered by the police revealed that the JVP was operating via a network of cells where members were indoctrinated by “Five Lectures” and directed to collect firearms and funds by robbing banks and individuals. Political rallies and clandestine meetings held by the JVP were gathering momentum and causing some serious concern to the government.

Around the beginning of March security around the Army cantonment at Panagoda was strengthened. Rumour was rife that there were elements of officers and soldiers sympathetic to the cause, if not members of the JVP. Extra precautions were taken to double the security of the arms and ammunition held in the camps. There was an air of suspicion and a lack of trust among the rank and file. There was also some concern that food and water was to be poisoned, so much so that the stray dogs in certain camps were fed before the troops.

In mid March a state of Emergency was declared with special powers of search without a warrant being entrusted to the Police. In conjunction with this the Army was to be deployed to assist the Police in search and cordon operations. Captain Satchi Ratnasabapathy from the Regiment of Artillery was sent to Hambantota to reconnoiter the area and liaise with the Police and Government Agent to assess the threats posed in the event of any actions initiated by the JVP that would disrupt the internal security of the region.

Meanwhile suspected high profile JVP activists and their leader Rohana Wijeweera were arrested and imprisoned in Jaffna. There was an assumption that the “Che Guevara” as they were referred to had plenty of sympathizers and supporters as there were several well attended, popular public meetings conducted in the Hambantota region. Intelligence reported that secret meetings of cell members were being held and basic military type training was being given to trusted cadres. JVP plans to collect weapons and raise funds by robberies etc were not taken seriously and pursued. The Hambantota/Tissamaharama district was considered to be a hotbed of JVP activity and identified as one of the most likely trouble spots in the island.

The deployment

At that time I was a lieutenant posted to 10 Battery at Trincomalee but was temporarily stationed at Panagoda in preparation for the Army inter-unit rugby tournament. On the evening of March 15 whilst at rugby practices I was summoned by the adjutant, Capt Siri Samarakoon, to his office where he told me in a voice dripping with sarcasm that I had won the lottery and was to take an IS (Internal Security) platoon and leave for Weerawila in the Hambantota district at the crack of dawn on March 17.

At the same time two artillery platoons from Trincomalee under the command of Capt Tissa Tillekeratne and Lt Lionel Balagalla were also to be deployed to Polonnaruwa and Hingurakgoda. There were other deployments to the Kegalle, Kandy, Anuradhpura and Moneragala districts from infantry and armoured corp detachments.

. On March 16 I was given my operational orders. I was also briefed by Capt Ratnasabapathy who assured me that based on local intelligence provided by the police he was of opinion that there was NO significant information of violent JVP activity in the Hambantota area but cautioned me about the wild elephants that roamed in the vicinity of the salt pans at night.

The platoon consisted of 31 men, which included three sergeants as section commanders and a cook. The platoon was armed with .303 rifles. A light machine gun (LMG) and three sterling sub machine guns (SMG) . As an officer I had the least effective weapon, a Smith and Wesson .38 calibre pistol that was more of a status symbol of authority. I was also issued with a sealed box of a thousand rounds of .303 ammunition with strict instructions not to break the seal unless absolutely necessary. It was also emphasized that I be very mindful of my personal security and that of the weapons at all times.

My transport was an old Willys jeep AY 3665 which on independence day parades looked very impressive, freshly painted with its windscreen down and hood taken off although it was patched up with paper and spray painted over to hide the rust and holes. There were three trucks detailed to carry the troops of which one would return to camp and the other, a new Indian five ton Tata Benz and a Beep (smaller version of a truck), to be used for operations. I was to be supplied with additional transport by the Government Agent Hambantota on my arrival in Weerawila.

On March 17 morning I left Panagoda at the crack of dawn having been bid farewell by Captain Noel Weerakoon who was the Battery commander of 11 Battery whose men I had taken charge of. He wished me “Good luck and God bless and take care of yourself “. Sadly it was a last farewell. He was killed in an ambush on April 8 at Ambewewa/Welioya. I think he was the first officer of the Army to be killed in action in this conflict and perhaps in the short history of the Ceylon Army.

The designated route was via Ratnapura and en-route we stopped at an army camp at Embilipitiya. The soldiers here had conveyed to some of the platoon that there were threats made of possible attacks on the camp via open postcards and were on extra guard duty.

Our base at Weerawila was to be the Old Tuberculosis hospital complex which had been uninhabited and abandoned. The GA and his staff had done their best to make this building habitable by restoring electricity and water.

The building we occupied, devoid of any furniture or fittings, was located in the middle of nowhere, isolated and off the main road and surrounded by dense overgrown shrub. In unfamiliar surroundings and not feeling secure I came to the conclusion that I could take no chances of being taken by surprise. The first thing I did was to disregard my orders and break the sealed box of ammunition and distribute some of it to the men and instruct them to keep their weapons by their side at all times.

Espirit de Corps and loyalty of the Regiment

It was a decision I made taking into consideration the utmost trust and loyalty of the soldiers under my command. “The Gunners” as those belonging to the regiment of artillery are generally referred to, were a close knit family (the gunner tribe) . Their loyalty and espirit de corps were always talked about in the army, best described in a message in the centenary celebrations of the Artillery in Sri Lanka in 1988 by the late Lt General Nalin Seniviratne, the commander of the army which said as follows:

“In the rich and colourful tapestry of Gunner history, an unbroken golden thread that runs across the entire fabric is that vibrant vitality of the Regiment, is their sense of unity and their espirit-de- corps “.

” Gunners are a unique family; in our family we the officers are very close to our men. The well being of our men has always been close to our hearts. We are proud of them,” as said by Lt Gen Hamilton Wanasinghe a gunner and a former Army commander would aptly describe the relationship we enjoyed. It was a unique bond between the officers and the men which made my decision so much easier at this time of great doubt and suspicion.

At Weerawila

Late in the evening two soldiers from the Ridiyagama farm that was being dismantled turned up and requested a guard. They too had received open postcards that their camp was to be attacked but had no weapons to defend themselves. I obliged by detailing two men. Unfortunately it became a daily assignment and was seen as a punishment chore. Weerawila was to be our home and operational base.

On March 18 I reported to The Government Agent Hambantota, Mr Sonny Goonewardene, who briefed me on the situation and reiterated that even though a state of emergency had been declared I was there only to assist the police and had no other powers. I was to work in liaison with the Assistant Superintendent of Police Tangalle, Mr Jim Bandaranayake who would coordinate my daily activities, in the absence of the ASP Hambantota. I was provided with two additional vehicles with civilian drivers to carry out my tasks.

The presence of the army in the Hambantota district may have intrigued the general public curious about why we were there. It was after a long time that the public had seen an army deployment in their locality and were perhaps bemused at the gun toting soldiers. The last time a military operation conducted in the Hambantota/ Tanamalwila area was in the late 1950’s named ‘Operation Ganja” where armoured cars and troops were used to destroy illicit ganja plantations in Tanamalwila and surrounding areas.

It was an operation made infamous for the unsuccessful legal action taken to prosecute Lt. Eustace Fonseka, a gunner officer, for the ill treatment meted out to the village headman of Hambegamuwa. who was alleged to be the mastermind and king pin of the ganja cultivation in the area. This operation was of a different nature.

Whilst we made our presence felt and were quite friendly the locals kept a fair distance from us wondering what the hell was going on.

Commencement of Operations /Searches

Initially we assisted the police traveling around the countryside in the military vehicles displaying our weapons which the police did not carry. We accompanied them to search homes of people suspected of involvement with the JVP. There was hardly any credible intelligence as most of our searches were more of a routine show of force and nothing else. There was no intimidation of the general public and not a single arrest was made in these joint operations.

One day when accompanied by the police sergeant at Walasmulla I observed that he was using these searches to intimidate some people whose political alliances were not the same as the govt in power. Every home and shop he took us into had a photograph of the former prime minister. It was not the first time this had happened but the continuation of this routine irked me.

This was not something that I could tolerate or an action that I could condone as it was in breach of my orders and furthermore the searches were fruitless. I contacted ASP Jim Bandaranayake and told him what was happening and that I was not prepared to assist the Police any further if this was all the intelligence they had.

Incidentally some months after the insurgency had been quelled the sergeant concerned was charged for the murder of some insurgents who were fleeing from army operations in the Sinharaja and Deniyaya areas being conducted by the army. They had been taken into custody by the police and on the pretext of being released shot and buried in a mass grave.

We continued to patrol and make our presence felt in Beliatta , Middeniya, Walasmulla, Ambalantota, Tangalle, Tissa, Kirinda and Hambantota with the assistance of the Police. We searched Wijeweera’s home in Tangalle occupied by his mother and sister. There were magazines titled ” Red China” and nothing else in this very clean and neatly kept house. This magazine was found in a number of places we searched including temples. His mother told us that she detested what her son was doing and had advised him to keep clear of politics. He had been arrested and imprisoned in Jaffna. They had a small poultry shed which I presumed gave them some sort of income.

Whilst there was very little of any material evidence to support an armed insurrection we did come across some very personal revelations. There was an instance when we found a diary of a person who had virtually kept a daily record of his sexual exploits in an affair with a girl across the road. The Kama Sutra may have been his manual. The sergeant who found the diary did not find the contents to his moral satisfaction darted across the road to the school nearby and divulged the contents to the head master. His audience showed no concern as perhaps they knew what had been taking place but were no doubt amused by the colourfully detailed narrative.

(To be continued next weekweek)

FEATURES

Some vignettes of Singapore and my move to UNESCO Paris

Excerpted from volume ii of the Sarath Amunugama autobiography

Before I conclude my description of a short but enjoyable stay in Singapore I would like to describe some features of antiquarian interest which have now disappeared in that concrete jungle. They all exemplify various aspects of Chinese culture which immigrants from the mainland brought along with them in their arduous journey to the British colonial outpost of that time.

Many of the migrants arrived with only the bare clothing on their bodies. They mostly came from Guandong [Canton] in south China in overcrowded ‘Sampans’ and swam to shore to build a new life for themselves and their families. They were tough seafarers and good swimmers. Fortunately for them both the Colonial British administration and European Christian Missionaries received them with open arms despite of the alarm of the Malays whose ‘homelands’ were being invaded.

It was more than a demographic transition. The new comers were more hard working and entrepreneurial than the traditionally lazy Malays, who being blessed by nature with an abundance of food and babies, were loath to compete with the Chinese. This was clearly seen in the preponderance of Chinese merchants in the cities of the Malay states and Indonesia.

The ‘Bhumiputras’ were concentrated as small farmers and artisans in their villages and as social anthropologists like Cliffied Geertz have brilliantly demonstrated led a highly stratified existence in the ‘Kampongs’ where symbolic values prevailed within a culture of great social complexity. The hostility of the Malay peasants to the Chinese merchants remained as an undercurrent which broke out as race riots in Malaysia in 1969 and the mass slaughter of Communists and Chinese [often they were the same] in Indonesia in 1965 during the American inspired military coup.

It was in this background that Lee Kuan Yew and his PPP defused the embers of racial violence and established the multi-ethnic state of Singapore. That was no easy task. But happily many of the features of mainland Chinese culture were recreated by the immigrants in their new Singapore home, albeit in a diminished form.

The migrants coming on shore were helped by Christian missionaries who set up soup kitchens, elementary schools that taught English and Christianity, especially extracts from the Bible, and found employment for them in the emerging ‘sweated trades’ in the Straits Settlements and the lower rungs of the colonial administration. Since canny Chinese migrants quickly adapted themselves to benefit from the goodwill of the missionaries, who were busy making a head count of their converts to impress their sponsors in Europe, they were called ‘Rice Christians’.

But this characterization may be unfair because many of these converts stuck to their new religion and as forward looking Christians contributed to the modernization of Singapore. They added to the ethnic mosaic in the demography of a region which was dominated by traditional religions like Islam which were ‘other worldly’ and not as partial to economic and social growth. A good example was the migrant entrepreneurial family of C.K. Tang which dominates retail business on Orchard Road. As orthodox Christians the Tangs do not trade on the Sabbath and their large departmental store remains closed on that day much to the discomfort of holiday shoppers.

Cheek by jowl of the huge skyscrapers we still see the dimunitive historical church buildings in which Christian priests provided hot soup and sermons to the weary migrants who had come to escape the famines and grinding poverty which then marked the mainland. Migrants created “China Towns” which even in the 1980s were crowded living and trading quarters “which never sleeps”. Anything from ancient esoteric Chinese medicines to pet snakes could be purchased in China Towns which offered different provincial cuisine from Cantonese to Sichuanese and Teochew to northern wheat based delicacies.

One could also savour Indonesian, Thai, and Tamil cuisine in the hole in the corner restaurants in the vicinity where the proprietor dressed in a singlet and Khaki shorts would shout out the orders to the cooks who plied their trade on pavements in the open air. All the makeshift tables had zinc tops and trestle like legs which could be dismantled in a short while and upended at the end of the day’s business.

Nearby were the ‘Death Houses’ where old men and women were often forcibly lodged by their relatives. These shriveled oldsters would look out of the windows of the upstairs in their virtual prison and shout out to the pedestrians below. They were all awaiting death as permitted by ancient Chinese custom. Another unforgettable experience in China Town was the Chinese haircut and head massage given in small `saloons’ which dotted its alleyways. The barber would pull out long thin metal rods to which cotton wool earbuds were attached.

They would be gently eased into the ears which were then manipulated to clean the insides of the unfortunate clients’ ear canal. This caused an excruciating but very pleasant sensation which cannot however be safely recommended except to the intrepid ‘out of the world’ experience seeker. I doubt whether it is practiced nowadays in cosmopolitan Singapore.

Another favourite of tourists to Singapore was Bugis street where every evening transvestites would gather in their hundreds and parade along the narrow streets which were full of bars and small restaurants which were packed with sightseers. Nearby also were the brothels with their small rooms open to the street. Clients would freely walk in and out of these hovels which were full of Indonesian and Malaysian girls who were probably forced into prostitution due to poverty.

The Singapore government which is highly puritanical nevertheless turned a blind eye to these tourist attractions. The Gaylang district was full of brothels which advertised their custom by displaying a large red lantern at the entrance to the premises.

A Change in Occupation

While I was introducing changes in AMIC which were welcomed by FES and our membership I received a message from the Director General of UNESCO to visit Paris for an interview for the post of Director of the newly formed International Programme for the Development of Communication [IPDC]. The formation of the IPDC had been endorsed by the General Assembly of UNESCO but the DG had taken some time over it because he was not sure what form it would take vis-a-vis his administrative powers.

But he had settled finally on the idea of a special programme which had more independence and power than the departments of UNESCO which he controlled directly. In the case of the IPDC it was to have its own President, Director, Secretariat and Governing Council. In the light of the political contestation between the superpowers on the subject of media and communication, M’Bow the DG thought it wise to tread warily on this issue. He wanted a Director who was acceptable to all power groups.

For the office of President of IPDC, which was an honorary post, he managed to get approval for Gunnar Garbo, the delegate of Norway and national hero who had participated in the Norwegian resistance to the Nazis. Garbo had also been the Norwegian Ambassador to Tanzania. He was a towering figure and was acceptable to all sides. I was interviewed for the post of Director who was to be the functional head of IPDC, as the boss of the Secretariat answerable to the DG of UNESCO. I informed FES of the offer and with their reluctant approval left for an interview in Paris.

My friend Manu Ginige had booked me into a comfortable hotel close to our embassy in Rue D’Astorg. On the Monday morning I caught a taxi to the UNESCO building in Rue Miollis where ADG Gerard Bollas office was located. Since I came every year since 1977 to Paris for UNESCO meetings this was familiar territory which fact added to my confidence.

At this cordial meeting with Bolla he recounted his visits to Sri Lanka as head of the cultural Division of UNESCO. In fact it was Bolla who had recruited Luciano Maranzi to restore the damaged Sigiriya frescos in 1968.1 got the sense that I would be selected because he inquired whether I could be in Paris by September for the General Conference. He asked me to also follow classes in the French language at the Alliance in Singapore.

I also found out that I was the only candidate endorsed by diverse political groupings within member states. There were several other candidates from India, Bangladesh and some African countries but I left Paris rather confident that I will be selected. True enough in about a week’s time I received a letter from M’Bow stating that I had been selected as the Director of IPDC and should assume duties as early as possible.

No doubt this was a plum post in the UN system but I faced a problem in that I had been at AMIC for less than six months and it would be embarrassing to face FES which had placed such confidence in me. One consideration which weighed in my mind was that the UN paid for the education of the children of its staff and my daughters would benefit immensely by studying in France. It also meant that we could live together as a family in the dream city of Paris, which would be a great boon because my daughters were at an age when they could enjoy life there.

I consulted the Board members of AMIC who were unhappy to see me go but appreciated the fact that it was a rare opportunity. Sir Charles Moses, doyen of Australian Broadcasting wrote a kind letter to me which conveyed the sentiments of the AMIC Board; “I need hardly say that I will miss you at AMIC meetings. Apart from my personal regard for you, I feel that AMIC has suffered a real loss with your departure. It is a tragedy that you could not have stayed a couple of years longer. But that’s looking at the situation from AMICs point of view.

“On my part I am delighted for your sake that you have received the UNESCO appointment and I know that UNESCO is lucky to have got you. I expect you to go a long way in that, fine organization-I hope to the top. If by any chance your travels, bring you close to Australia please find some reason to spend a, day or so in Sydney and it would give me great pleasure to have you lunch or dine with me at my Club – the best in Australia.”

So with less than a year in Singapore I was now ready to go west to Paris and undertake a job which had been the focus of the hopes of many who looked forward to a more equitable and balanced new Information Order in the world. I was extremely lucky that it was a dream assignment in a territory that I was specially equipped to traverse. It was a rare opportunity to make a dream come true and I made ready to relocate in the ‘City of Light’.

FEATURES

The mystery of the chains on Adam’s Peak

by Hugh Karunanayake

“Now the island of Serendib lies under the equinoctial line, its night and day both numbering twelve hours. It measureth eighty leagues long by a breadth of thirty, and its width is bounded by a lofty mountain and a deep valley.The mountain is conspicuous from a distance of three days, and it containeth many kinds of rubies and other minerals: and spice trees of all sorts. I ascended that mountain and solaced myself with a view of its marvels which are indescribable, and afterwards I returned to the king.” – from the Sixth voyage of Sinbad the Sailor- the Arabian Nights (9th century)

Known to Buddhists as Sri Pada, to Hindus as Sivan-oli-padam, and Muslims as Baba Adamalai, the religious association of this mountain in central Sri Lanka is mainly due to an impression on stone at the summit which resembles a footprint. In fact, during medieval times, centuries before the new world including the Americas, Africa, and Australia was discovered, there was no mountain in the world of which there was so widespread knowledge as Adam’ Peak in Ceylon, or variously known to ancient travellers as Serendib, or Taprobane, or Ceylom.

Adam’s Peak served as a magnet to the great travellers and adventurers who traversed the seas, spending years of travel, often dissipating personal fortunes in the process. The famed travellers of yore from Venice, China, and the Middle East who traversed the oceans centuries before steam ships and aircraft were invented all made their way to the famed island in the Indian Ocean. Fa Hien, Marco Polo, and Ibn Batuta all visited the island during their travels, and the lure of Adam’s Peak would have been a major attraction.

The first Englishman to ascend the mountain was Lieutenant Malcolm of the First Regiment who reached the summit on April 27, 1827. It has been said that the peak could be seen out at sea from a distance of nine days travel from the shores of Ceylon. In fact Adam’s Peak is the only mountain in the world from which an uninterrupted view around it could be seen, and in this instance, right up to the shores surrounding the island. The peak could be seen on a clear day from the Galle Face Hotel in Colombo, and from the Royal College cricket grounds. No other mountain the world including the mighty Everest provides such a panoramic view of the surrounding country. Little wonder therefore that this mountain

attracted the attention of the most renowned travellers and explorers of medieval times.

Adam’s Peak which projects skywards out of the wilderness of the land around it, involves a climb of over 7,000 feet. Towards the summit where vegetation ceases to exist, the mountain takes a conical shape with a very steep ascent which is almost impossible to climb were it not for the support provided by iron chains and an iron ladder riveted to the rock. These chains and the ladder are of great antiquity, pinioned on to the face of a perpendicular cliff close to the summit.

Muslims believe that the iron chains were fixed by Alexander the Great. The Zaffer Namah Sekanderi, a fifteenth century Persian poem by Asreef which celebrated the exploits of Alexander describes thus “he fixed thereto chains with rings and rivets made of iron and brass, the remains of which exist today, so that travellers by their assistance are enabled to climb the mountain and obtain glory by finding the sepulchre of Adam.”.

The first international traveller who mentioned the existence of these chains was Marco Polo in 1292, and subsequently Ibn Batuta who ascended the peak in 1347 who also mentioned it. Sinhalese records however reveal that the chains were fastened on to the rock by King Vijayabahu(1058 – 114 AD). The Mahavansa records a stipulation by King Vijayabahu which stated ” Let no one endure hardship who goeth along the difficult pathways to worship the footprint of the Chief of Sages on Samantakuta Mountain”.

Henry Cave writing in 1895 stated that ” the history of these rusty chains with their shapeless links of varying sizes bearing the unmistakable impress of antiquity, is involved in myth and mystery. The chain near the top is said to have been made by Adam himself, who is believed by all true followers of the Prophet to have been hurled from the seventh heaven of Paradise upon this Peak, where he remained standing on one foot until years of penitence and suffering had expiated his deed.’

Ibn Batuta who climbed Adam’s Peak about a century before Asreef, mentions the “ridge of Alexander’ at the entrance to the mountain, and a minaret there named after Alexander. There is however no reference in any other historical document or chronicle to confirm that Alexander the Great ever visited Ceylon. The mystery regarding the origin of the chains remain, to baffle historians and antiquarians. Perhaps our modern day archaeologists could help throw some light on this mystery??