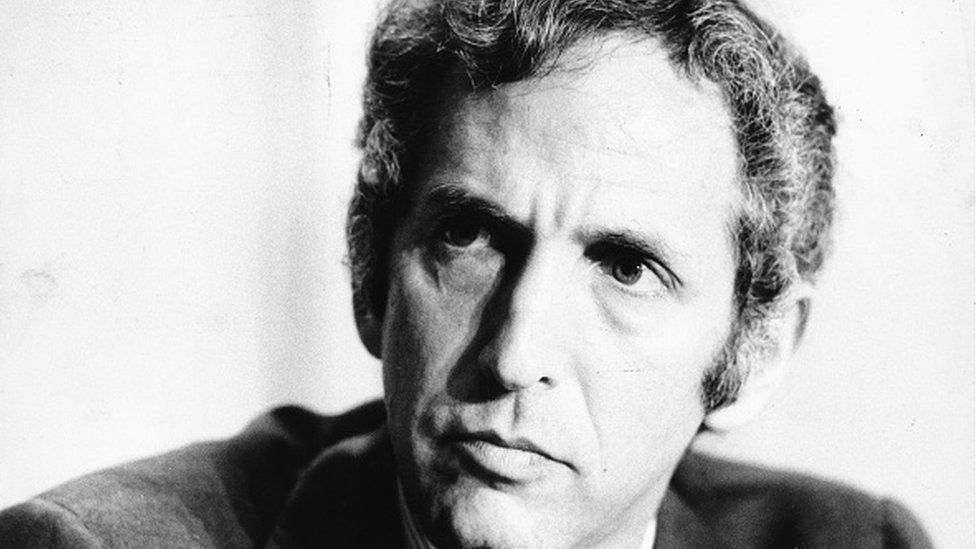

Daniel Ellsberg: Pentagon Papers whistleblower dies aged 92

-

Published

2022 interview: Pentagon Papers whistle-blower Daniel Ellsberg says he was a secret back-up for Wikileaks

Daniel Ellsberg, the whistleblower who exposed the extent of US involvement in the Vietnam War, has died, aged 92.

He died at his home in Kensington, California, of pancreatic cancer, his family said.

The former US military analyst’s 1971 Pentagon Papers leak led to him being dubbed “the most dangerous man in America”.

It led to a Supreme Court case as the Nixon administration tried to block publication in the New York Times.

But espionage charges against Ellsberg were ultimately dismissed. “Daniel was a seeker of truth and a patriotic truth-teller, an anti-war activist, a beloved husband, father, grandfather, and great-grandfather, a dear friend to many, and an inspiration to countless more. He will be dearly missed by all of us,” Ellsberg’s family said in a statement obtained by NPR.

For decades, Ellsberg was a tireless critic of government overreach and military interventions.

His opposition crystallised during the 1960s, when he advised the White House on nuclear strategy and assessed the Vietnam War for the Department of Defense.

What Ellsberg learned during that period weighed heavily on his conscience. If only the public knew, he thought, political pressure to end the war might prove irresistible.

The release of the Pentagon Papers – 7,000 government pages that exposed deceptions by multiple US presidents – was a product of that rationale.

The papers contradicted the government’s public statements on the war and the damning revelations they contained helped bring an end to the conflict and, ultimately, sowed the seeds of President Richard M Nixon’s downfall.

Ellsberg was “the grandfather of whistleblowers”, the former chief editor of The Guardian newspaper, Alan Rusbridger, told the BBC.

His intervention “radically changed the public opinion in the Vietnam War”, Rusbridger said on Radio 4’s World Tonight programme. The case against him set a precedent and “no US government has ever tried to injunct a paper on grounds of national security since”, he said.

The Pentagon Papers created a First Amendment clash between the Nixon administration and The New York Times, which first published stories based on the papers – cast by government officials as an act of espionage that compromised national security. The US Supreme Court ruled in favour of the freedom of the press.

Ellsberg was charged in federal court in Los Angeles in 1971 with theft, espionage, conspiracy and other counts.

But before the jury could reach a verdict the judge threw out the case citing serious government misconduct, including illegal wiretapping.

The judge said that in the middle of the case he had been offered the job of FBI director by one of President Nixon’s top aides.

It also emerged that there had been a government-sanctioned burglary of Ellsberg’s psychiatrist’s office.

Ellsberg was born in Chicago on 7 April 1931, and grew up in the suburbs of Detroit, Michigan. Before reaching the Pentagon, he was a Marine Corps veteran with a Harvard doctorate who had worked for the Defense and State departments.

According to Rusbridger, recent whistleblowers such as Julian Assange and Edward Snowden were “moulded by” Ellsberg.

He told the BBC that the Pentagon Papers case had prompted him to think “who gets to define the national interest: is that the government of the day or people with a conscience like Daniel Ellsberg?”

Ellsberg continued his quest to hold the government accountable years after the Pentagon Papers leak.

During an interview in December 2022, he told BBC Hardtalk that he was the secret “back-up” for the Wikileaks documents leak.

In the Wikileaks case, Julian Assange’s organisation published more than 700,000 confidential documents, videos and diplomatic cables, provided by a US Army intelligence analyst, in 2010.

Ellsberg said he felt Mr Assange “could rely on me to find some way to get it [the information] out”.

In the wake of a diagnosis of pancreatic cancer in February, in which doctors told Ellsberg he had three to six months to live, he spent recent months reflecting on the Pentagon Papers and whistleblowing more broadly.

In a March 2023 email obtained by the Washington Post, Ellsberg wrote: “When I copied the Pentagon Papers in 1969, I had every reason to think I would be spending the rest of my life behind bars. It was a fate I would gladly have accepted if it meant hastening the end of the Vietnam War, unlikely as that seemed.”

Politico released an interview with Ellsberg on 4 June and, within it, the publication asked him whether whistleblowing is worth the risk despite his view that it has not made the government any more honest.

“When we’re facing a pretty ultimate catastrophe. When we’re on the edge of blowing up the world over Crimea or Taiwan or Bakhmut,” he replied.

“From the point of view of a civilization and the survival of eight or nine billion people, when everything is at stake, can it be worth even a small chance of having a small effect?” he said. “The answer is: Of course… You can even say it’s obligatory.”