Whistleblowing banker who went to prison speaks out

-

Published

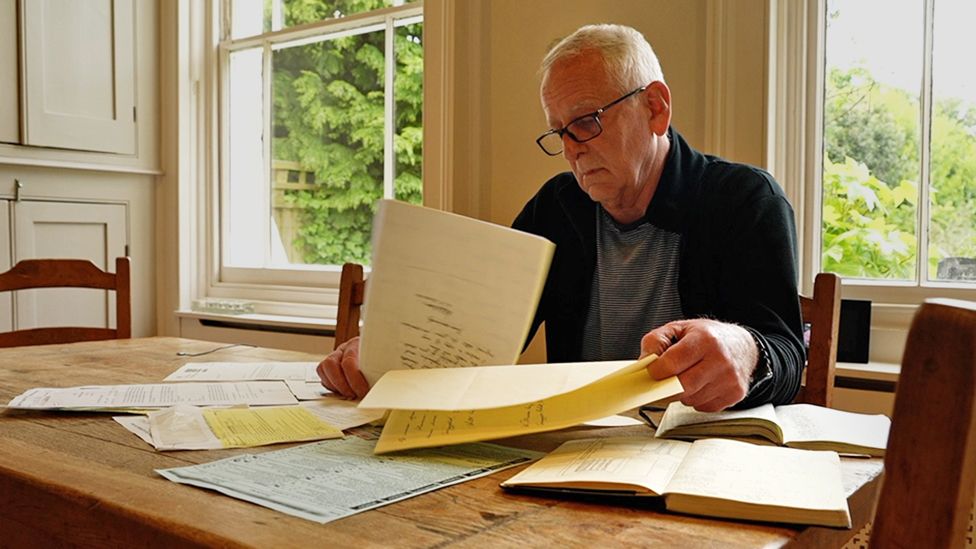

Peter Johnson: “Telling my father… I felt embarrassed, I felt ashamed”

A former Barclays trader jailed in connection with a $9bn interest rate rigging scandal has said telling his father about it was “the hardest day of my life”.

“I burst into tears. I felt like I’d let him down,” Peter Johnson told the BBC, as he struggled to compose himself.

In an emotional interview, Johnson revealed the devastation caused not only to his life but that of his family by what is now regarded by some MPs as a state-level cover-up, followed by a whole series of miscarriages of justice.

Jailed for four years for “manipulating” interest rates, Johnson was released in 2018 after serving two years.

He was later revealed to be one of the original whistleblowers of the scandal.

Speaking for the first time since his release, he says when he was put on gardening leave by Barclays in 2011, he descended into depression and avoided being seen in the streets near his house or informing his family about his predicament.

In 2012, Johnson was sacked by Barclays after more than 30 years’ service and faced the risk of prosecution by the US Department of Justice (DoJ), which could lead to up to 30 years in a US prison.

“[When I woke up] I’d have about five seconds when I thought all was well with the world. And then I’d realise that it wasn’t. And I’d go around all day with a sort of a weight pressing against my chest. I’d wait for six o’clock before I started self-medicating with alcohol. I had panic attacks,” he says.

“I spent years trying to suppress my emotions because I don’t want to get upset and bitter and twisted and everything else.

“[But] this is too important to forget – to sweep under the carpet. People need to know and once they know the full facts, they can make their judgements on whether what people did was wrong or right.”

Such was the psychological pressure on him that when he was charged with a crime in the UK, rather than the US, it came as a relief.

“It was ridiculous. There I was feeling relieved that I was going to be charged with a crime. And it was good! I mean, it’s just stupid. It just shows how mad things were for me at the time.”

Johnson’s lawyer Tony Woodcock, now retired but then a senior partner at prominent white-collar crime specialists Stephenson Harwood, sees his former client’s prosecution as an outrage.

Senior MPs including former Brexit secretary David Davis and former shadow chancellor John McDonnell have come to share that view after reading a book I have written exposing the scandal.

“In over 30 years in practice I never had a case in which I felt so powerless and bullied and where the smell of politics was so rancid. Hopefully all the evil lurking in the mud will be found out,” Mr Woodcock says.

One reason he feels so strongly is that Johnson, who worked as a cash trader for Barclays from 1981 to 2011, was the original whistleblower of the interest rate rigging scandal, in which banks paid nearly $9bn in fines and 37 traders and brokers were prosecuted for “manipulating” Libor and Euribor, two benchmarks that track the cost of borrowing cash.

From 2007 to 2009, Johnson repeatedly alerted the US central bank and the Bank of England to other banks publishing false, low estimates of the interest rates they’d have to pay to borrow hundreds of millions of dollars at a time – so-called “lowballing”.

He tried to publish higher, more honest estimates, but kept getting instructions from above to be no more honest than any other bank. Leaked audio recordings indicate the pressure on Johnson to lie came first from the board of Barclays, then from the Bank of England, then from the UK government.

Evidence revealed in the book indicates that then-Prime Minister Gordon Brown’s head of policy, the late Sir Jeremy Heywood, was one senior Whitehall figure who wanted Barclays to lower its Libor estimates of the cost of borrowing dollars.

“I thought they were wrong,” says Johnson. “But I didn’t feel I had any choice but to go along with them. You’re being asked by the UK government and the supreme financial establishment in the land to do something. It’s very, very difficult to say, ‘No, stuff you!'”

Yet four years later, on 27 June 2012, suppressed anger towards the banks at the lack of accountability for the 2008 banking crisis exploded into the media when Barclays was fined a record £290m by US and UK regulators for rigging interest rates.

Both Labour and Conservative MPs angrily condemned 14 unnamed traders – which Johnson knew included himself.

“When something like that happens to a major corporation, there’s usually a scapegoat. And I sort of felt that maybe it might be me.

“Quite justifiably, the public was outraged at what they saw as excesses in the banking industry. And they wanted heads on a pike. And I became one of the heads,” he says, adding: “I think they could have chosen better ones.”

Criminal authorities on both sides of the Atlantic, co-operating with lawyers working for Barclays, lined him up for prosecution.

He was not prosecuted for lowballing, but for manipulating rates on a much smaller scale by accepting requests from traders between 2005 and 2007 to nudge his Libor rates up or down very slightly.

In 2014, Johnson became the first banker to plead guilty to manipulating interest rates. But it was only because he felt the odds were against him and he had no choice. Barclays had cut him off from any financial support with his legal fees.

Because of the very high cost of defending himself, he feared he might lose his home, his savings and therefore his ability to support his children and grandchildren, even if he were found innocent.

“I didn’t feel as if I’d done anything wrong. But I could see the way the whole thing was going and it didn’t look good for me.”

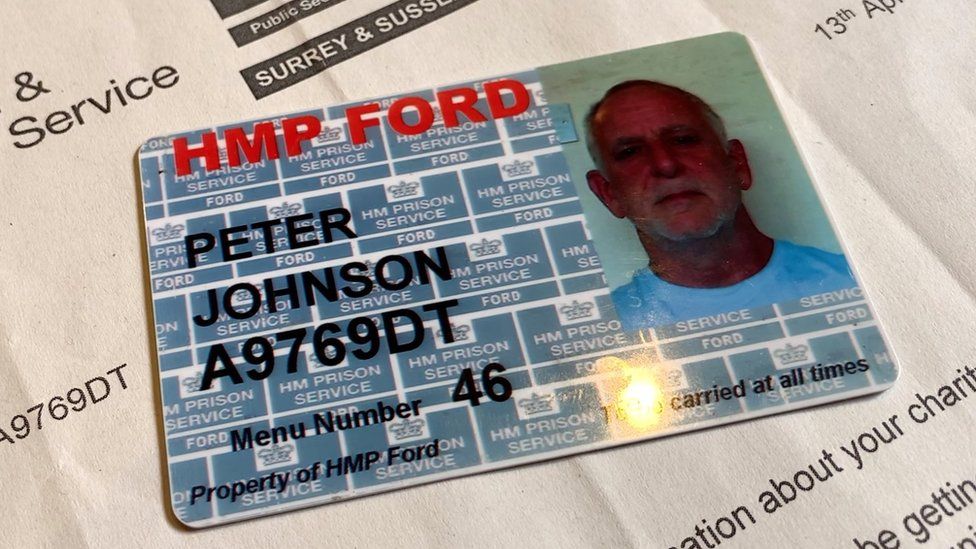

Johnson, a 68-year-old grandfather, was sentenced in 2016 to four years and jailed alongside three other Barclays traders.

His first jail was HMP Wandsworth, which he describes as “pretty basic, pretty horrible”.

“There was a shortage of prison officers… and there are some times when we were not let out of our cells, apart from for 10 minutes to get our meals, for 54 hours at a time.”

He was later transferred to Ford open prison, where he decided to improve his fitness by walking around the perimeter of the prison, clocking up 6,000 miles and raising £3,000 for charity.

In the US, all 19 convictions for interest rate rigging are being overturned at the request of the DoJ – the same body that originally declared conduct like Johnson’s to be illegal – following a US appeal court ruling that the prosecution case was misconceived.

The trader requests that Johnson was jailed for, it found, were not illegal – and didn’t even break any rules. Many of those convictions arose from guilty pleas, made under the threat of prosecution in the US, which the DoJ no longer views as sound.

The UK is now the only country where making or accepting the requests is viewed as criminal. David Davis, John McDonnell and other MPs, peers and senior lawyers have written to the Times saying the cases must be sent back to the courts.

“In my most optimistic view, I would like my guilty plea to be revoked. I’d like to basically have my reputation restored. And I’d like senior people to be held accountable,” says Johnson.

Asked who they are, his reply is simple: “The board of Barclays Bank, the Bank of England and the government of the UK.”

Barclays declined to comment for this article.

A spokesperson for the Serious Fraud Office, which prosecuted Johnson, said its cases were based on evidence. It said nine bank traders knowingly rigged rates for their own benefit. “Separate juries and the Court of Appeal agreed they committed a crime.”

A Bank of England spokesperson said: “The Bank fully co-operated with the Serious Fraud Office’s investigation into Libor manipulation, responding to all requests for information and documents.”

The Treasury said in a statement: “The government did not seek to influence individual bank Libor submissions.”

Follow Andy Verity on Twitter @andyverity