The firms giving nature a stake in their businesses

-

Published

Outdoor clothing company Patagonia made headlines last year when it announced that Planet Earth “is now our only shareholder”.

If that sounds somewhat confusing, the actual detail behind the statement revealed what the firm meant.

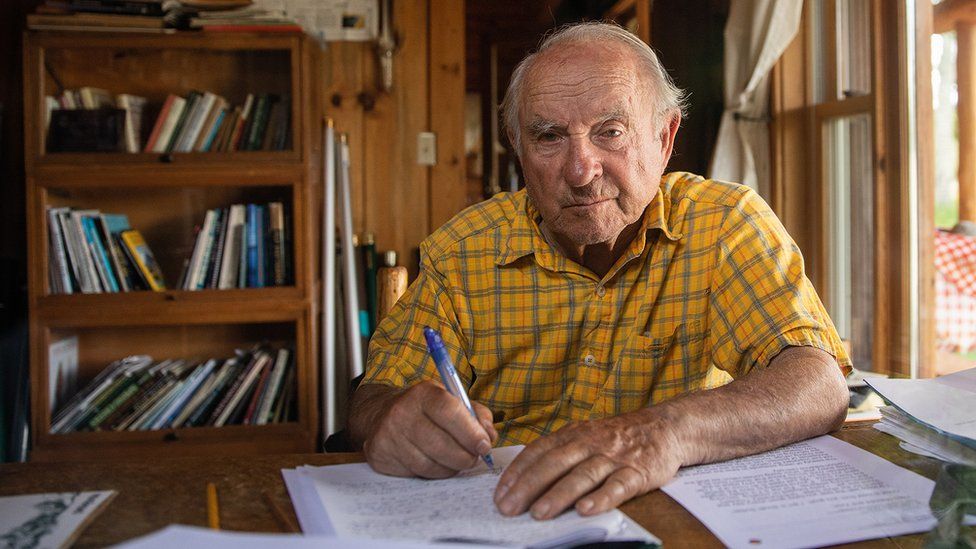

The founder and former owner of the California-based business – Yvon Chouinard – had decided to transfer 98% of the company’s shares to a new environmental organisation called the Holdfast Collective.

Every year Holdfast will receive all the profits that Patagonia doesn’t need to reinvest, to “protect nature and biodiversity” and “fight the environmental crisis”. The amount of money is expected to be more than $100m (£78m) every 12 months.

Meanwhile, the other 2% of the retailer’s shares were transferred to a new trust, called the Patagonia Purpose Trust, which now runs the company, and – as the firm says – guides its environmental and philanthropic principals.

Yvon Chouinard, who led Patagonia for 50 years, is now 84 years old. He and his family decided on the new business structure and cash giveaway as he stepped back from being in the company’s driving seat.

“We looked at different approaches,” says Patagonia’s chair Charles Conn. He adds that one option could have been floating the firm on a stock exchange and “then give the money away”, but that may have resulted in the company subsequently not being run in such an environmentally-focused way.

“So we kept coming back to giving shares to environmental foundations, and using it to fight the environmental crisis,” says Mr Conn. “It’s a radical thing to do, but we’re dependent on Mother Earth.

“The family walked away from billions, but Yvon is the real deal. He doesn’t have a mobile phone, they drive old cars.”

You might think that Patagonia is an unusual one-off, but a small number of other firms are making similar arrangements to add nature and the environment – at least figuratively – to either their ownership or board rooms.

UK beauty products company Faith in Nature now has two directors who are there “to give nature a voice and a vote on how Faith In Nature is run”. These two external board members come from two environmental organisations – Earth Law Centre and Lawyers for Nature.

“It’s about how to make business better, so less damage is done,” says Anne Hopkins, creative director at Faith in Nature.

“We are a company with our hearts in the right place… we didn’t want this to just be marketing. We wanted to create a formal and legal structure with a practical framework.”

Fellow creative director Simeon Rose adds that the two environmental directors come to an agreement “and give nature’s view”. He adds: “The biggest difference is now it enables other board members to see what decisions nature makes, and it helps them make further conscious decisions”.

Faith in Nature, which was founded back in 1974, has now created an online guide for any companies that would like to follow its example.

In the Netherlands, Dutch vegan cheese-substitute company Willicroft appointed “Mother Nature” as its chief executive in 2020, replacing co-founder Brad Vanstone, who became head of impact.

But what does that actually mean?

“It means that every single decision we make every day is geared towards the planet. For example, I now take the train when I travel to the UK, whereas before I wouldn’t think about it, and I would fly,” says Mr Vanstone.

Since the new boss was appointed, other environmental decisions made by Willicroft include only accepting investors who are committed to ditching any fossil fuel investments within five years.

In addition, the firm switched from making its cheese substitutes out of cashew nuts to using beans and pulses instead. This was because it calculated that the processing of cashews caused more carbon emissions.

Global Trade

Mr Vanstone adds that next year the business will bring in an “impact board” to sit alongside the main board of the company, to challenge any decisions not deemed environmentally led.

In addition, he has called for other businesses to follow Willicroft’s nature-led lead, and he says that 15 companies in Amsterdam have now followed suit.

The actions of Patagonia, Faith in Nature and Willicroft seem easy to celebrate, but they are not without their critics.

Kandi White, program director at US environmental group Indigenous Environmental Network describes such initiatives as “largely greenwashing and empty gestures”. Her organisation was set up in 1990 to protect the “sacred sites, land, water, air, natural resources, [and] health” of indigenous communities across North America.

“Even with a symbolic recognition of Mother Earth as a board member, or donating profits to philanthropic organisations, climate justice will not be achieved until the practice of profit and consumption ends,” she says.

“Corporations must change how they relate to Mother Earth, to nature, and must dispel the dominant anthropocentric belief that Mother Earth belongs to humans. Lastly, they must establish values, principles, operations and practices that are reflective of natural law.”

Still, for companies wishing to add an environmental representative to their ownership or board, Tad Ostrowski, founder and managing director of UK law firm Artington Legal, says they should carry out due diligence first.

“Care would need to be taken to ensure that the finances of the company and the relationships with the other shareholders were clear, transparent and aligned with the company and its relevant stakeholders,” he says.

“But done properly, there is no reason why the company’s long-term success for the benefit of its members as a whole cannot be linked to positive decision making for the long-term benefit of nature.”

Back at clothing firm Patagonia, Mr Conn says it was vital to put Planet Earth in charge of the business. “Many species are in decline, and climate change is impacting us all. Like Yvon says, there’s no business on a dead planet.”