FEATURES

Acquisition of AF Jones, my very first business venture – Differences with S. Nadesan, QC

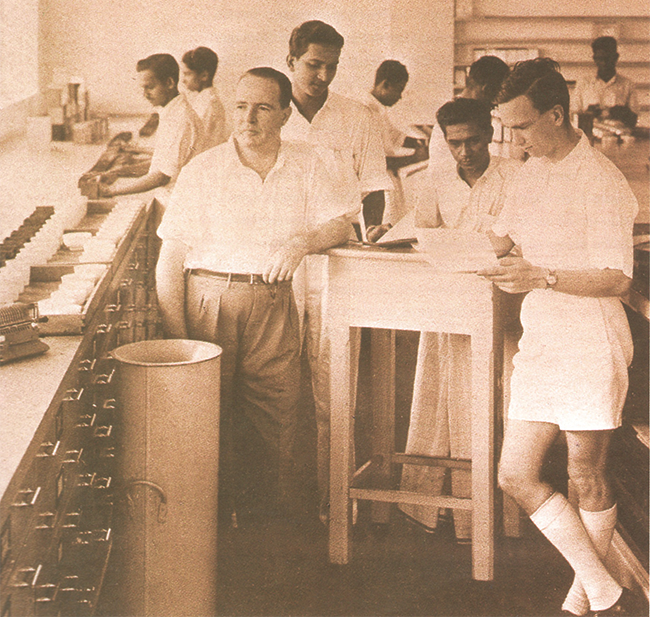

A. F. Jones —Tea Tasting Room — Alan Jones in the foreground

(Excerpted from the autobiography of Merrill J. Fernando)

The new political climate and the State-orchestrated business direction seemed calculated to discourage the continuity of foreign investment presence in the country. In this environment, in 1962, the Jones family, unsurprisingly but with great reluctance, decided to sell and move out of the country. They had been in business since 1912, when their ancestor, AF, had arrived in Ceylon from Batavia and launched the company under his name. The decision to sell out was compelled by adverse circumstances beyond their control.

They offered the company to me, at the reasonable price of Rs. 600,000. However, it was still beyond my means on my own and I turned to my friend, Sarath Wijesinghe. He agreed to join me in my investment and we decided to take a third each. It was my intention to split my share with members of my family. For the balance share of the company, I approached S. Nadesan, a well-known lawyer and senator, for whose legal skills I had developed a great respect, on account of his successful representation of my interests in a legal issue with a relation.

He agreed to come in as the third partner. In retrospect, my decision to take over A. F. Jones was both bold and risky in the context of the political environment then, which seemed clearly unfriendly to large-scale private enterprise. However, I was young and, with the confidence of youth, not averse to risk. That apart, I had great faith in my competence in the tea export industry, reinforced by the knowledge and experience of overseas markets I had acquired by then, along with very useful business contacts in a number of tea-importing countries. Underpinning all those considerations, there was my sublime faith in God.

Irrespective of the risk inherent in my maiden entrepreneurial venture, the other factors which worked in my favour were the strong trade links that AFJ had established by then with Iran, Iraq, and Libya, USA, and South America. I had been actively involved in many of those initiatives. I was also singularly fortunate, in having been able to establish early direct links with major international packers and blenders, often bypassing the latter’s agents in Colombo.

With my dedicated and resourceful team I was able to provide the buyer with an exceptional service, shipping out over the weekend the tea that had been purchased at the auctions on the Tuesday before. None of the larger firms operated with that degree of efficiency then. As the owner-operator of a small firm, I was also able to take business risks and also employ operational strategies that the larger firms were not prepared to consider. That apart, I was fortunate in being able to command the complete loyalty of my small group of employees, who willingly shared with me the stress and pressure generated in the business.

However, business operations require funding and, with the departure of the Jones family and the company now being entirely in ‘native’ hands as it were, I was apprehensive that bank facilities would be restricted. The company had been operating on an overdraft of Rs. 1.1 million around the time I acquired control. The Jones family had been trying for some time, without success, to increase it to Rs. 2 million.

An unexpected offer

A. F. Jones banked primarily with National and Grindlays Bank, Colombo, the local subsidiary-associate of the National Bank of India. The Managing Director of the Ceylon branch then was a British national, W. L. Gash, whom I had met on a couple of previous occasions. Even in those brief meetings he came across as a fair-minded, reasonable person. Once the transfer formalities were concluded and the company operations were in my hands, I went to meet Gash in order to update him on the changes in the company. Before the meeting, as was my custom in all important situations, I visited the All Saints’ Church in Borella and spent a few minutes in prayer.

I explained to Gash the circumstances under which I had taken over responsibility for the company and requested him to continue the financing facilities that existed earlier. To my very pleasant surprise he asked me whether I would like it increased to Rs. 2 million, as per the pending request made by the Jones family. Frankly, I was at a loss for words at this unexpected blessing. Naturally, I accepted with thanks and immediately went back to All Saints’ Church to thank God for his benediction. Included in my prayer was Mr. Gash, my new benefactor on earth.

To a great measure, my early success at A. F. Jones was due to the assistance of Mr. Gash. He always accommodated my requests, even when they seemed unreasonable. In fact, some of the senior managers at the bank used to be very surprised at the enhancement of the bank’s exposure to my business, extended with minimum collateral and mortgages and sans personal guarantees.

Around this time I was offered a very nice house in Colombo at a reasonable cost, of which I would have been able to meet only about 20% from my personal resources. I went to Mr. Gash and inquired whether he would loan me the balance 80%. Again, to my utter surprise, he loaned me the full value against an undertaking to mortgage which, finally, was not required.

Internal strife at AFJ

The company’s business progressed well, though there were difficult issues I had to contend with from time to time. At one stage Nadesan, now a Director of the company, persuaded me to take two of his family members on to the Board and to employ other relatives as well. One such was an individual recommended as Personnel Manager, married to a lady heavily involved in Leftist party politics. Unaware in these connections I appointed him, but, to my dismay, soon found that he was trying to unionize the company’s workforce. Since this was clearly against the company’s interests, I was compelled to persuade him to leave.

When the Jones brothers finally left, they offered me the balance shares they still held in the company. I immediately turned to Mr. Gash who very kindly agreed to arrange a loan at low interest for the purchase. When I mentioned this to Nadesan, he advised me against obtaining a loan and, instead, offered to buy the shares and to hold them in trust for me, to be sold to me at a future date. Mr. Gash was strongly against this arrangement and tried to persuade me to take the loan instead, pointing out that my personal acquisition of the shares would tip the balance of power in the company in my favour, automatically conferring on me greater authority in operational matters. However, trusting the word of my fellow Director, I agreed to the latter’s proposal.

As we moved on with the business of the company, Nadesan brought both his son and brother on the Board and also prevailed on me to employ more of his relatives. His son, somewhat arrogant and confrontational, tried to impose his will in business matters he was not familiar with. In 1962, at a Board meeting, he presented some proposals which I considered to be against the company’s interests. Since I was in disagreement, at that point I requested Nadesan to transfer to me, for a proportionate payment, the shares he was holding in trust for me. He agreed and we adjourned the Board meeting.

To my dismay, later on in the day, at my home, he admitted to me that he had purchased the shares in his son’s name and that the latter would not part with them on any condition. However, he tried to appease me with the assurance that I would be permitted to run the company without interference.

I exit the company

I realized that I had been deceived by a man I trusted, respected, and looked upon as a mentor. However, in view of the circumstances, unfortunately, I had no choice but to carry on. The business did continue to grow but the working environment became steadily more unpleasant and, at a Board meeting on September 4, 1962, 1 announced my firm intention to resign, but under certain conditions.

I requested that the flat I had leased out eight years previously and transferred to the company, in order to get a tax benefit, be transferred back to me, and that the motor car I was using also be transferred to me at book value. I also asked that all my other dues be settled within two weeks. All my requests were approved by the Board and we parted on those conditions.

The next day I received a letter from the company giving me just seven days to leave my apartment and requesting me to send the car to the agents for valuation. Whilst I had no difficulty in the re-transfer of the lease of the apartment, I was advised that the car would not be sold to me.

My experiences with A. F. Jones and the manner of the conclusion of that relationship, made me realize that trust is not always reciprocated. It was also an early lesson to me in the potential for duplicity, even amongst those who work closely with you. Another experience whilst at A. F. Jones provides a good example of the latter.

In the Imports arm of A. F. Jones – Eastern Agencies – there was an executive named Chuck Wijenathan, who was ,to all outward appearances, a very nice man. When I was appointed Managing Director of A. F. Jones, I proposed that he too be appointed a director. Nadesan initially opposed the idea but my wish prevailed and Wijenathan was brought on to the Board a few months later. Wijenathan was present at the meeting of September 1962, when the Board agreed that I could move out of the company on my terms. However, no sooner the meeting was concluded, Wijenathan was the first person to call up various people and announce that I had been fired from the company.

Despite such disenchanting early experiences, I have continued to operate on the assumption of mutual trust, although being frequently cautioned by my sons and close friends against being too gullible. -My philosophy is that if you maintain integrity on your part, human decency will prevail and the good will eventually outweigh the bad. Notwithstanding a few disappointments over the years, I am still firmly of the same view.

Along with several other principals, Eastern Agencies Ltd. also represented the famous drug manufacturer, Merck Sharp & Dohme Inc. and Rowntree’s Chocolates Ltd. Since import volumes were low, I once placed a large order for chocolates, without realizing that the company had minimal reserves. When the consignment arrived in the port, to my great embarrassment, I was advised by the wharf clerk that we had no money to pay the duty.

I sought help from Mr. Gash who, despite being unaware of our import operations, loaned the sum of Rs. 410,000 that was needed to clear the cargo. However, our wharf clerk, a man who had been a company employee for several years, carried out a ‘black-market’ operation with the consignment, compelling us to claim from insurance in order to repay the bank. Despite these marks the company was able to restructure its financing model and start making money.

The Nadesans eventually transferred the Eastern Agencies business to the Satyendra family and thence to the Maharaja Group, the manner of the transaction depriving AFJ of a valuable asset at no great benefit to its shareholders. My first exposure to the ‘modus operandi’ of supposedly-reputed legal luminaries was an eye-opener.