NEWS

Former Foreign Secretary outlines enormity of Indian poaching in Lankan waters depriving our fishermen’s livelihood

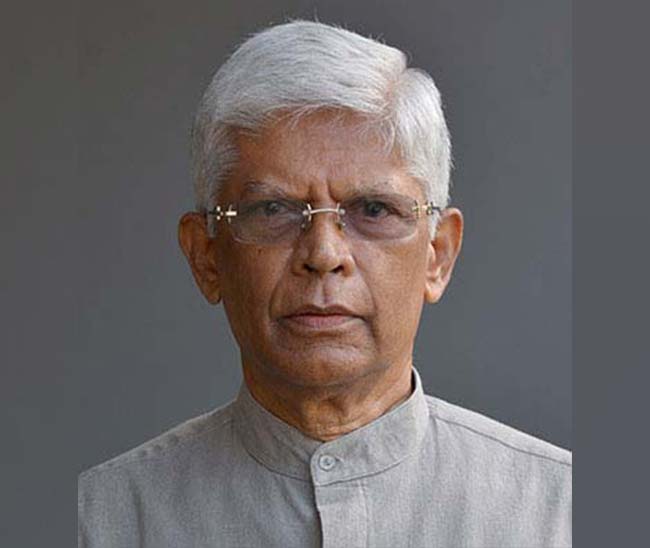

Bernard Goonetilleke

By Rathindra Kuruwita

There are about 3,500 trawlers operated by Indian fishermen operating around South India, out of which about 2,000 poach in Sri Lankan territorial waters, Bernard Goonetilleke, Chairman of the Pathfinder Foundation, said.

He said that Indian fishermen arrive about 500 meters from Sri Lanka’s shores three days a week, adding that a few years ago, it was estimated that Sri Lanka lost about 80 million U.S. dollars due to poaching and that the number should have increased significantly by now.

In the first few decades, following independence, Sri Lankan and Indian fishermen operated without boundary restrictions, Goonetilleke said.

However, agreements signed in 1974 and 1976 demarcated sea boundaries, the retired Foreign Secretary said. The 1974 Agreement was regarding historic waters between Sri Lanka and India in the Palk Strait and Palk Bay. This agreement also formally confirmed Sri Lanka’s sovereignty over the Kachchativu Island.

Article 5 of the 1974 Agreement states that “subject to the foregoing, Indian fishermen and pilgrims will enjoy access to visit Kachchativu as hitherto, and will not be required by Sri Lanka to obtain travel documents or visas for these purposes.”

Article 6 of the Agreement states that “vessels of India and Sri Lanka will enjoy in each other’s waters such rights as they have traditionally enjoyed therein.”

In this article, only the navigational rights of the vessels of both Sri Lanka and India over each other’s waters have been preserved.

An Agreement between Sri Lanka and India on the Maritime Boundary between the two countries in the Gulf of Mannar and the Bay of Bengal and related matters was signed in 1976.

The Agreement said “each party shall have sovereign rights and exclusive jurisdiction over the Continental Shelf and the Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) as well as over their resources, whether living or non-living, falling on its side of the aforesaid boundary,” it said adding that “each Party shall respect rights of navigation through its territorial sea and exclusive economic zone in accordance with its laws and regulations and the rules of international law.”

The 1974 and 1976 Agreements, taken together with the Exchange of Letters, that was signed between Kewal Singh, the then Foreign Secretary to the Government of India, and W.T. Jayasinghe, then Secretary to the Ministry of Defence and Foreign Affairs of Sri Lanka, has put the question of fishing rights beyond doubt. Paragraph 1 of the Exchange of Letters very clearly rules out any fishing rights for the fishermen of the two States in the waters of the other state which reads as follows; “fishing vessels and fishermen of India shall not engage in fishing in the historic waters, the territorial sea and the EEZ of Sri Lanka, nor shall the fishing vessels and fishermen of Sri Lanka engage in fishing in the historic waters, the territorial sea and the EEZ of India, without the express permission of Sri Lanka or India, as the case may be.”

While Indians lost access to Sri Lankan waters, local fishermen lost access to Pedro Bank, and Wadge Bank, the continental shelves off Cape Comorin at the southern tip of India, which had been profitable commercial fishing grounds since the 1920s for both Indian and Sri Lankan boats.

Goonetilleke said that although these agreements were signed, Sri Lankan fishermen were absent from the seas off the country’s north for about 30 years due to the war with the LTTE.

“We had to restrict the movement of Sri Lankan fishing boats. During that time, Indian fishermen operated in our waters freely. They still come to our waters based on that habit,” he said.

The Chairman of the Pathfinder Foundation said that Indian trawlers are large and numerous. Because of this, they have managed to compel Sri Lankan fishermen to stay home for three days of the week.

“Usually they operate on Monday, Wednesday and Saturday. They ask our fishermen not to operate on those days. Our boats are usually under 23 feet. When they lay the nets and wait, and if large Indian trawlers engage in bottom trawling or pair trawling, they can drag away our nets, our catch and even our boats. When this happens, there is often conflict,” he said.

Indians, for the past few decades, have been asking Sri Lanka to issue permits to their fishermen to operate in Sri Lankan waters, the Chairman of the Pathfinder Foundation said. However, there is stiff opposition to this among the Sri Lankan fishermen, he said.

“Sri Lanka has banned bottom trawling in 2017/18. Earlier, circa 2010, Indian fishermen, during a discussion with Sri Lankan counterparts, agreed to stop bottom trawling by 2012. The 2018 regulations note what steps are to be taken against Indians who poach in our waters.

“However, given that most of the Indians arrested do now own the boats and Sri Lanka’s recognition that these fishermen are compelled to take these jobs due to poverty, the 2018 law has a number of humanitarian provisions. For example, when we arrest Indian fishermen, we have to tell the Indian consulate, legal action has to be taken within 30 days, and we do not harass them while in custody. However, we only arrest a handful of them when they come to our waters three days a week and in fleets of thousands,” he said.