Hong Kong: Jimmy Lai’s trial highlights rule of law concerns

-

Published

After three-and-half years in jail, Jimmy Lai was finally ushered into a Hong Kong courtroom to stand trial for treason.

He was brought in through the back door, so only those inside the courtroom on Monday saw the democracy champion, who Beijing calls a “notorious anti-China element”.

Noticeably thinner and gaunt, the 76-year-old sat facing three judges who will decide his fate over the coming months.

He has denied all charges, arguing he was only defending freedoms in Hong Kong, the city where he built a fortune.

Mr Lai cannot expect a fair trial in today’s Hong Kong – although authorities will argue otherwise, his lawyers in London told the BBC.

“You still have the apparent institutions in place, you still have the buildings, you still have judges, you still have lawyers. But in fact, the fundamental principle of the rule of law is eroded,” says Jonathan Price, a barrister on Mr Lai’s international legal team which cannot represent him in Hong Kong.

“Everybody knows there’s only going to be one result – it’s absolutely plain.”

Mr Lai is one of at least 250 Hong Kongers arrested since 2020 for allegedly endangering national security.

Like many charged, he has been denied bail, the right to a jury and his choice of lawyer to represent him in court.

Hong Kong insists it is still underpinned by the rule of law, upheld by a common law legal system inherited from the British. It’s what made the city an international banking hub; it holds on to that image and continues to seek foreign investment.

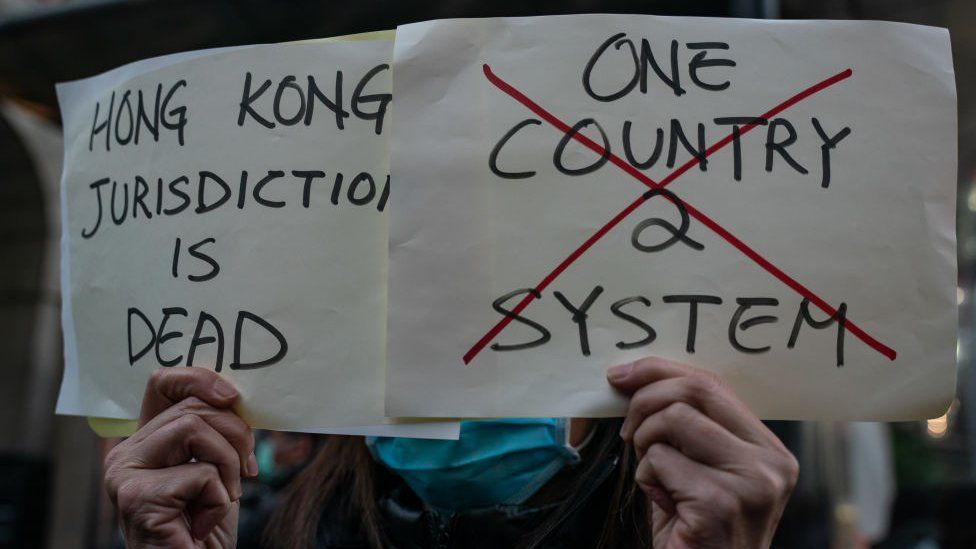

But critics say the city has changed irrevocably under Beijing’s authoritarian rule, which crushed pro-democracy protests in 2019-2020 and imposed a sweeping National Security Law (NSL) that punished dissent.

Mr Lai, who faces the rest of his life in prison if convicted, embodies the “whole gamut of what has happened to Hong Kong”, Mr Price says.

The media mogul, whose Apple Daily tabloid was vociferously critical of Beijing, was frogmarched out of his newsroom in a police raid in August 2020, two months after the NSL took effect.

In December 2020 while out on bail, Jimmy Lai spoke to the BBC just hours before he was taken back into remand again

He was charged with “collusion with foreign forces”, and accused of seeking to destabilise Hong Kong.

Prosecutors pointed to articles questioning Hong Kong’s future and calls for international sanctions against its officials.

He was later also charged with leading a pro-democracy protest and attending a banned vigil for the victims of the 1989 Tiananmen Square massacre in Beijing.

He was sentenced to 14 months for “unauthorised assembly” and given five years in 2022 for a separate offence of fraud, related to a lease violation.

It was a stunning takedown of one of Hong Kong’s most outspoken businessmen: a rags-to-riches fashion entrepreneur who made millions with the polo-shirt chain Giordano before starting up a newspaper, a decision driven by the 1989 massacre of protesters by troops in Beijing.

During the 2019 pro-democracy protests in Hong Kong, Mr Lai would join the tear-gassed crowds and listen to protesters before returning to the newsroom to direct coverage.

The media mogul was seen as near untouchable, with resources many thought put him beyond the state’s reach.

But in fact his case, legal scholars say, shows just how vulnerable anyone is in Hong Kong when they speak up for democracy.

Not only has Mr Lai had bail repeatedly denied, but the British citizen’s choice of lawyer, UK silk Timothy Owen KC, was also barred by authorities.

Despite foreign lawyers having operated for decades in the city’s courts, the Hong Kong government last year decided they posed a national security risk, and would need permission to work on any NSL cases.

This came after Hong Kong’s leader John Lee challenged the city’s top court ruling and asked Beijing to “interpret” the law’s powers.

Mr Lai will also not face a jury, although that has been the norm in previous criminal legal cases carrying life sentences in Hong Kong.

Under the NSL, the government has the power to deny a jury and appoint a panel of three judges. They have done so for every NSL defendant so far.

Hong Kong’s Department of Justice told the BBC this “seeks to safeguard rather than undermine the defendants’ right to a fair trial”. But Mr Lai’s lawyers appealed, arguing his judges have been hand-picked by Hong Kong’s leader.

Hong Kong legal scholar Eric Lai says the NSL upended long-standing legal principles overnight: “We’re dealing with pretty vague and wide-ranging legislation – and so many of the procedural safeguards have been swept away.”

For those charged under the NSL, “the presumption now is against the right to bail”, says Prof Lai.

So defendants have to argue they should be released from custody as opposed to the onus being on prosecutors to keep them in jail.

Legal monitors say nearly four in five have been denied bail.

The authorities say every NSL bail ruling has been “handled fairly and adjudicated impartially”. The justice department told the BBC the “cardinal importance of safeguarding national security… explains why the NSL introduces more stringent conditions to the grant of bail”.

But Alvin Cheung, who worked as a Hong Kong barrister and lecturer for years before leaving the city, says: “The whole point of the government’s strategy is to keep people in pre-trial detention, a legal limbo, for as long as possible.”

Those imprisoned under the NSL have previously told the BBC they felt the tactic was aimed at exhausting and demoralising them.

That’s how Hong Kong authorities operate now, Prof Cheung says: “You try them on the first day, charge them with a second thing and repeat the exercise over and over again.”

Hong Kong’s government also boasts of the 100% conviction rate in NSL cases so far. But that is a damning statistic, according to legal experts.

“No properly functioning justice system should operate in an environment where there’s a 100% conviction rate, it can’t be right. It’s redolent of a sham democracy where a dictator claims to have 98% of the popular vote,” says Mr Price.

The NSL, which Hong Kong says targets subversion and secession, has been used to jail pop stars, lawyers and politicians who led the pro-democracy movement.

One prominent case involves “the Hong Kong 47”, campaigners and legislators who sought to organise a primary during the 2020 election.

But ordinary people have also been caught in the dragnet, as authorities have resurrected use of a colonial-era sedition law. Mr Lai is also being tried under this law.

In November, 23-year-old Mika Yuen was sentenced to two months over Instagram messages – “I am a Hong Konger; I advocate for HK independence” – while studying in Japan.

She was arrested under the NSL, but her charges were later changed to sedition. She is the first to be convicted for something done outside Hong Kong.

In June, single mother Law Oi-wah was convicted of sharing pro-democracy slogans on Facebook. She was denied bail and her 12-year-old son begged for her release at her sentencing – but she was jailed for four months.

“These are not revolutionary bomb-throwing people, these are people who simply wanted to express an alternative view. But that’s the dangerous thing to do now,” says Michael Fisher, a Chinese University of Hong Kong law professor who left the city this year.

“Things that five years ago we took for granted: freedom of expression, freedom to demonstrate – these have all been effectively eroded or destroyed.”

When Britain returned Hong Kong to China in 1997, the treaty specified that the territory would have its political freedoms and rights preserved for another 50 years.

The government says that citizens’ rights, including that to a fair trial, are still protected by the city’s constitution, or Basic Law. But political and legal experts say NSL has superseded those rights.

All of this has led to a shrinking pool of legal professionals, as lawyers and judges are among the 100,000 people who have left Hong Kong since 2020, by some estimates.

“Some defendants have decided to proceed without lawyers because they lacked confidence in the lawyers who were assigned,” wrote legal scholar Johannes Chan, the former dean of the University of Hong Kong law school who resigned in 2021 and moved to the US.

Others without means have had to accept prosecutors as their public defenders.

The former leader of Hong Kong’s Bar Association has left, and three foreign judges – including two UK Supreme Court justices – have resigned from Hong Kong’s top court.

Judges Lord Robert Reed and Lord Patrick Hodge wrote in 2022 that the city’s courts “continue to be internationally respected for their commitment to the rule of law” but in line with the UK government’s view, they could not “continue to sit in Hong Kong without appearing to endorse an administration which has departed from political freedom, and freedom of expression…”

That was evident outside Jimmy Lai’s trial in the West Kowloon courts.

At previous hearings, crowds used to gather, queuing with signs and copies of Apple Daily, but on Monday, just one veteran protester dared raise her voice.

Waving the territory’s old Union Jack flag, the activist known as Grandma Wong shouted: “Support Jimmy Lai! Stand up for the truth!”

She was quickly surrounded, and taken away by police.