Features

Ranil skips two presidential elections backing common candidates Fonseka and Sirisena

By Tisaranee Gunasekera

(first published in Himal Southasian)

(continued from last week)

Mahinda’s victory (in 2005) marked an inflection point. He did not abrogate the ceasefire agreement he had inherited, and even engaged in a round of negotiations with the LTTE. At the same time, he allowed the Sri Lankan military a freer rein. In December 2005, for instance, the navy retaliated to an LTTE bombing by attacking a residential area in the northern town of Mannar.

In 2006, the JVP, then in Mahinda’s alliance, filed a case in the Supreme Court seeking the abolition of an earlier merger of the Tamil-dominated North and East, effected in 1987. Fighting escalated and the ceasefire collapsed. Mahinda and Gota – by then appointed the secretary to the ministry of defence – followed the LTTE’s example by opting for a strategy of total war.

The fighting finally ended in 2009 with mass civilian deaths and the extermination of the LTTE. Thousands of Tamil survivors were incarcerated in prison camps. The Rajapaksas intended this to be a permanent arrangement and dismantled them only due to strong international pressure. The victory, and the refusal to make any political concessions to the Tamils, turned the two brothers into Sinhala national heroes.

The Rajapaksas’ drive to stamp out dissent and centralize power in their own hands began while the war was still raging. Part of the process was a wave of murders, abductions and disappearances. After the end of the war, the 18th Amendment removed presidential term limits and the few remaining checks on the president’s power. Rajapaksa family members hogged key ministries and state institutions.

Allegations of corruption mushroomed, defence expenditure soared, and the militarization of civilian spaces accelerated. Tamil areas were placed under de facto military rule and a new campaign commenced to demonize another minority, the Muslims. An international borrowing spree and high indirect taxes financed prestige infrastructure projects with little economic viability. The Rajapaksa model, which would culminate in Sri Lanka’s bankruptcy and the Aragalaya, was born.

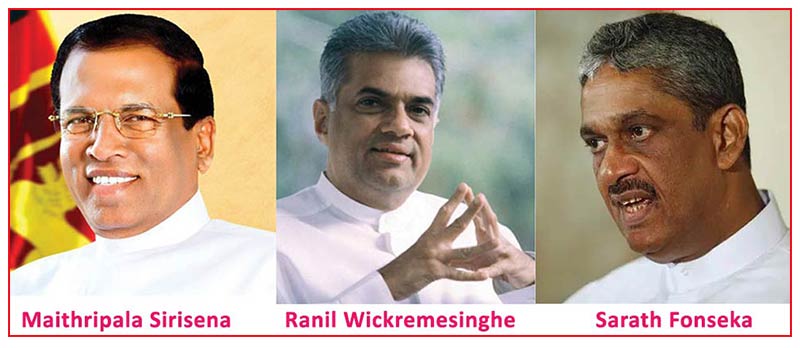

Over nine years of Rajapaksa rule, Wickremesinghe remained on the back foot. He was nominally the leader of the opposition but spent more time and effort combatting dissenters within the UNP rather than the government. His focus was on retaining party leadership, not gaining the presidency. In 2010, he willingly conceded the presidential candidacy of a united opposition to Sarath Fonseka, the war-winning army commander, knowing well that Mahinda was bound to win that year’s presidential election.

Wickremesinghe defeated a couple of challenges to his leadership, reportedly with some Rajapaksa help. In 2011, for instance, a UNP faction backing Sajith Premadasa planned to hold a satyagraha outside the party’s headquarters to demand an open leadership contest. On the day, the road leading to the headquarters was closed by the police to facilitate urgent repair work by the ministry of highways. The brewing rebellion collapsed.

BY 2014, Wickremesinghe had been the leader of the UNP for 20 years but had recorded just one victory in a parliamentary election, in 2001, and one in local government elections, in 2002. It was a lacklustre record by any standard. By this time, the slogan “Ranil Can’t” had gained currency even within Wickremesinghe’s own party.

So when Mahinda called an early presidential election, and electoral trends hinted at his possible defeat, fielding Wickremesinghe as a common opposition candidate was not even considered. Maithripala Sirisena, the general secretary of the SLFP and a key minister in Mahinda’s cabinet, was picked for the role after he agreed to defect from the government during secret negotiations. Wickremesinghe went along on the understanding that he would be made the prime minister in a future Sirisena government.

With economic distress, anti-incumbency, minority voters and corruption allegations all acting against the Rajapaksas, Sirisena convincingly won the 2015 presidential election. But it was far from certain whether the Rajapaksas would honour the electorate’s decision or try to cling to power via extra-constitutional means. According to media reports, when he realized the election was lost, Mahinda summoned the commanders of the armed forces, the Inspector General of Police and the attorney general to check with them about the possibility of overturning the results, and was advised not to by all of them.

In the end, Mahinda accepted the verdict and stood down, and Wickremesinghe was pivotal in ensuring that outcome. In the early hours of January 9, he visited Mahinda and reportedly brokered a smooth transition. Mahinda, according to accounts at the time, was worried that he and his relatives would face harassment and arrest by the Sirisena government, or have their security removed. Wickremesinghe delivered assurances of security and protection, and the deal was done.

He was the right man for such a delicate job with so much riding on it: violence was a certainty if Mahinda refused to accept the election result and leave. Wickremesinghe had excellent relations with most of the country’s political leadership, ranging from the Rajapaksas and ex-president Kumaratunga to the JVP.

Sirisena appointed Wickremesinghe as his prime minister and the latter was sworn in for thethird time. Wickremesinghe retained the post after the UNP won a plurality at the parliamentary election that soon followed. He performed exceptionally well at the polls, with a personal preference vote of over 500,000 – a record at the time. The Rajapaksas, having failed to regain control of the SLFP, found their own party, the SLPP, in 2016.

The new administration christened itself the Yahapalanaya, or “Good Governance”, government. Its inaugural budget brought in a slew of popular measures. Indirect taxes were slashed, bringing prices down, while direct taxes were increased. Public-sector employees were given a pay hike and their peers in the private sector asked to follow suit. Sirisena and Wickremesinghe also shepherded through the 19th Amendment, which reduced the powers of the presidency and re-imposed term limits on the office. For a brief while, it looked as if the new government might live up to its chosen name.

It did not take long for the public mood to sour and for Wickremesinghe’s star to crash back down to earth. The Yahapalanaya government appointed a new Central Bank governor – Arjuna Mahendran, Wickeremesinghe’s pick and known friend. The bank then held a bond auction where a large portion of the bonds went to a company linked to Mahendran’s son-in-law with suspiciously high interest rates. When the scandal broke, much of the outrage attached to the prime minister, and delays in investigating the matter were blamed on his interference. Until then, Wickremesinghe had not been saddled with any significant allegations of corruption. Now he became synonymous with what was remembered as the Bond Scam.

Other unpopular measures, such as handing a deep water port in Hambantota over to China on a 99-year lease, were also blamed on him. The port had actually been Mahinda’s pet project, built in his home district at enormous cost and against much advice as part of his debt-fueled infrastructure push. The government defended the deal as a way to bring in some much-needed cash as Sri Lanka struggled to pay its soaring foreign debts – including massive sums due to China, which had been glad to bankroll Mahinda’s spree.

Contrary to persistent allegations, Sri Lanka did not take on unprecedented debt during the Yahapalanaya years. That administration proved to be a more responsible economic steward than the Rajapaksas. The country’s total debt stock did rise sharply on its watch, but almost 90 percent of that was down to servicing loans taken out prior to 2015.

At local government elections in 2018, the UNP was trounced. Wickremesinghe was rightly held responsible and the discontent with his leadership of the party reached new heights. He suffered more damage with his handling of anti-Muslim riots that same year. The trouble began in the town of Teldeniya, in the centre of the country, where Sinhala Buddhist mobs went on a rampage. It soon spread through the surrounding district of Kandy. As things escalated, Wickremesinghe appeared inexcusably silent. By the time the government finally restored order, after a week of unrest, Wickremesinghe’s twin images as crisis-manager and minority-protector were in tatters.

Then, in October 2018, came the 52-day coup mounted by Sirisena in alliance with Rajapaksa. Sirisena dismissed Wickremesinghe as prime minister and appointed Mahinda to the position. When it became clear that Mahinda lacked a parliamentary majority, Sirisena dissolved the parliament.

Uncharacteristically, Wickremesinghe stood firm. He would not concede the premiership or accept the dissolution of parliament. In a symbolic move, he refused to vacate Temple Trees and opened the hallowed mansion’s doors to UNP members. He led the battle against Sirisena and Rajapaksa both within and outside parliament – building alliances with other opposition parties, reaching out to civil society groups and mobilizing party activists. In a career deficient of inspiring moments, it was perhaps his finest hour.

The reason for his activism was perhaps not hard to comprehend. Wickremesinghe was fighting to save his own seat, of course, but there was also the fact that Sirisena’s actions were unconstitutional. Wickremesinghe, the constitutionalist, was fighting for and within the constitution. The Supreme Court eventually confirmed that Sirisena had exceeded his authority and Wickremesinghe got to keep his post. Once the battle was won, Wickremesinghe as prime minister returned to his uninspiring ways.

There was one last test. In April 2019, on Easter Sunday, a local Islamist group carried out coordinated bombings at three churches and three luxury hotels. Sirisena was caught out of the country and out of his depth. The state apparatus was left headless, with no one taking charge, and there was real fear of reprisals against Muslims. Wickremesinghe stepped into the breach, rallying the police and military to apprehend the surviving conspirators and maintain civil peace.

But, once again, his charmlessness betrayed him. The media and public chose to focus on his supposedly unsympathetic manner during a visit to one of the bombed churches. Instead of winning praise for his leadership after the attacks, he was blamed for not stopping them – even though Sirisena had cut him out of the loop on security matters and did not allow him to attend the National Security Council after October 2018.

Wickremesinghe intended to contest the 2019 presidential election. But, under pressure even within his own party, he had to concede the candidacy to Sajith Premadasa. Gota contested as the SLPP candidate since the 19th Amendment had reintroduced term limits, disqualifying Mahinda. His campaign was based on anti-Muslim hysteria, and he swept to victory on an unprecedented wave of Sinhala support.

In early 2020, when Premdasa decided to go his own way, Wickremesinghe failed to stop a split in the UNP or prevent the party’s voters from moving en masse to Premdasa’s new SJB. Even after his party – and he himself – suffered humiliation in the next parliamentary election, Wickremesinghe held tight to the party leadership. No attempt was made to build up a new generation of activists and leaders, to revive the once-grand party now reduced to a solitary legislative seat. In political terms, Wickremesinghe sank into near non-existence. It was the nadir of his career.

In an interview with a local channel in 2021, he was asked whether he spent his nights plotting a comeback. “I’m watching Netflix at night,” was his prompt reply. That seemed to be the final word. Except that it wasn’t.

(To be continued)