Features

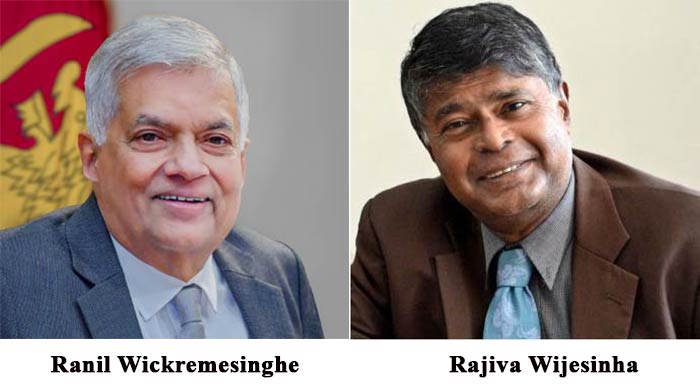

Rajiva Wijesinha on Ranil Wickremesinghe

By Uditha Devapriya

I was perhaps a little overenthusiastic, in trying to claim objectivity for Rajiva Wijesinha’s latest book, when I said at the launch on Tuesday, December 17, at Lakmahal, that the role of the political commentator and observer is not to pass judgments, but rather to lay bare the facts for the reader to decide. During the Q and A I was bluntly – and justly – critiqued by a member of the audience: no, he said, the role is not to overwhelm the reader with facts – it is to come to conclusions, to make the reader aware.

I was perhaps a little overenthusiastic, in trying to claim objectivity for Rajiva Wijesinha’s latest book, when I said at the launch on Tuesday, December 17, at Lakmahal, that the role of the political commentator and observer is not to pass judgments, but rather to lay bare the facts for the reader to decide. During the Q and A I was bluntly – and justly – critiqued by a member of the audience: no, he said, the role is not to overwhelm the reader with facts – it is to come to conclusions, to make the reader aware.

I am not sure whether this country is ready for another book on Ranil Wickremesinghe. It has been not quite three years since Wijesinha came out with a book – a grand expose, in my view – of J. R. Jayewardene. There was much to commend about that particular work, in particular its evisceration of K. M. de Silva’s and Howard Wriggin’s biography. It was only halfway through that I realised how sordid and irredeemable things had become since 1977, when the entrenchment of corruption took on new, unprecedented proportions. But then I realised that Wijesinha was not writing a dirge for the way things were, rather a revelation of where we are now, and as importantly, what we can do about it.

Ranil Wickremesinghe and the Emasculation of the United National Party (2024, Neptune Publications) follows Wijesinha’s trajectory of political writing. The book is full of tragedy and pathos, and bathos. It does not lay the sole blame for what has happened to the country, and the UNP, on Wickremesinghe – as Dayan Jayatilleka noted his speech, he is a protagonist set against a wider dramaturgy. But Wickremesinghe is not a bit player either – he emerges as the culmination of everything that the UNP did to itself, and to the country, until 1994. Viewed that way, Wijesinha’s book is a worthy successor to his study of Jayewardene – though as he told me before the event, there just isn’t anyone of K. M. de Silva’s intellectual calibre to take on the task of Wickremesinghe’s biography today.

The book begins with a look at some of the few good men the UNP produced in the 1970s, including Gamini Jayasuriya and Ranjith Atapattu. They were, as Wijesinha notes, honest and utterly scrupulous. But they were also in a minority, and typical of the Jayewardene regime – which even his biographers admit left a wide berth for corruption – they were sidelined. Wijesinha does his best to exonerate those who remained – the lesser evils – among whom he lists the then Finance Minister, Ronnie de Mel. The way he frames it, the turning point was the 1982 election, the subsequent referendum, and the 1983 riots. It is at this juncture that the party abandoned all pretences to statesmanship.

Ranil Wickremesinghe surfaces at this point. Wijesinha leaves no stone unturned in his critique of the man, including his parliamentary interventions after the 1983 riots. But to be fair by Wickremesinghe himself, the UNP had already deteriorated by then. Deprived of its liberal wing – one which Wijesinha traces to the death of Dudley Senanayake – it embraced authoritarianism with much enthusiasm. In a way, one could say this was inevitable: Sri Lanka was the first South Asian country to impose neoliberal capitalism on its economy, and as was typical of such countries, it modelled itself along the lines of other authoritarian capitalist states, including of course Singapore. Wijesinha does not critique the opening up of the economy itself – he implies, correctly I believe, that it was inevitable at that point. He finds fault instead with the manner in which it was done.

Although Wijesinha does not explicitly bring them up, I see parallels between this and Wickremesinghe’s handling of the economy after 2022. Economists and civil society were by 2022 agreed that there was no alternative to the IMF – simply because the Gotabaya Rajapaksa government had exhausted all other options. Yet Wickremesinghe’s reforms – highly orthodox, even if supporters claimed them to be radical in the run-up to elections this year – shifted the burden to the middle-classes. I should perhaps not quote extensively from Wijesinha’s book, yet the following passage is insightful.

“But what the IMF had requested before agreeing on the funds was acted on only insofar as the less well off were targeted, as with the new tax regime that burdened the middle classes disproportionately. What Ranil did nothing about was the restorative justice the IMF and the country wanted, bringing those who had plundered the country to justice and getting back at least some of the ill gotten gains.”

What we saw during the Wickremesinghe presidency – a point Wijesinha does not touch on that much – is the diminution of support he had hitherto secured from the upper echelons of the Colombo liberal intelligentsia. I distinctly remember an apologia, of sorts, penned by a group of writers calling themselves “Some Colombo Liberals” in September 2019, in the run up to presidential elections that year, stressing that “the UNP does not belong to liberals and there is no need to support the party to identify as a liberal.” Yet there was a time, not too long ago – during my teenage years – when it was fashionable, in order to be identified as a liberal, to support the policies Wickremesinghe adopted.

Which brings us to the elephant in the room, the million dollar – or rupee – question that the book leaves us with: what, exactly, constitutes liberal politics in Sri Lanka? Some would identify it with the centre-right, others with the centre-left. But is there a centre-right or centre-left in this country? As a friend of mine told another friend on his way out after the launch ended, “What is socialist?” Once could well ask, “What is liberal?” and still get the same, stony silence such questions provoke. Perhaps it was foolish to identify the liberal mainstream with Wickremesinghe, or for that matter the UNP – at least in its post-1977 iteration. But one point keeps coming back to me: though Wickremesinghe’s career may have ended, for now, the ghost of his ideas remains. In a way, that may be his strength and biggest trump card: ensuring that his ideas survived even his downfall.

Uditha Devapriya is a regular commentator on history, art and culture, politics, and foreign policy who can be reached at udakdev1@gmail.com. Together with Uthpala Wijesuriya, he heads U & U, an informal art and culture research collective.