Batalanda Skeletons, Victims’ Sorrows and NPP’s Tasks

Batalanda memories still torture them

Few foresaw skeletons of Batalanda come crashing down in a London television interview. There have been plenty of speculations about the intended purposes and commentaries on the unintended outcomes of Ranil Wickremesinghe’s Al Jazeera interview. The more prurient takes on the interview have been about the public dressing down of the former president by the pugnacious interviewer Mehdi Hasan. Only one person seems convinced that Mr. Wickremesinghe had the better of the exchanges. That person is Ranil Wickremesinghe himself. That is also because he listens only to himself, and he keeps himself surrounded by sidekicks who only listen and serve. But there is more to the outcome of the interview than the ignominy that befell Ranil Wickremesinghe.

Political commentaries have alluded to hidden hands and agendas apparently looking to reset the allegations of war crimes and human rights violations so as to engage the new NPP government in ways that would differentiate it from its predecessors and facilitate a more positive and conclusive government response than there has been so far. Between the ‘end of the war’ in 2009, and the election of President Anura Kumara Dissanayake and the NPP government in 2024, there have been four presidents – Mahinda Rajapaksa, Maithripala Sirisena, Gotabaya Rajapaksa and Ranil Wickremesinghe – and as many governments. Of the four, Ranil Wickremesinghe is the least associated with the final stages of the war and its ending. In fact, he was most associated with a failed, even flawed peace process that ultimately ensured the resumption of the war with vengeance on both sides. RW was also the most receptive to war crimes investigations even proffering that external oversight would not be a violation of Sri Lanka’s Constitution.

One school of thought about the Al Jazeera interview is that those who arranged it were hoping for Ranil Wickremesinghe to reboot the now stalling war crimes project and bring pressure on the NPP government to show renewed commitment to it. From the looks of it, the arrangers gave no thought to Ranil Wickremesinghe’s twin vulnerabilities – on the old Batalanda skeletons and the more recent Easter Sunday bombings. If Easter Sunday was a case of criminal negligence, Batalanda is the site of criminal culpability. In the end, rather than rebooting the Geneva project, the interview resurrected the Batalanda crimes and its memories.

The aftermath commentaries have ranged between warning the NPP government that revisiting Batalanda might implicate the government for the JVP’s acts of violence at that time, on the one hand, and the futility of trying to hold anyone from the then government accountable for the torture atrocities that went on in Batalanda, including Ranil Wickremesinghe. What is missing and overlooked in all this is the cry of the victims of Batalanda and their surviving families who have been carrying the burden of their memories for 37 years, and carrying as well, for the last 25 years, the unfulfilled promises of the Commission that inquired into and reported on Batalanda.

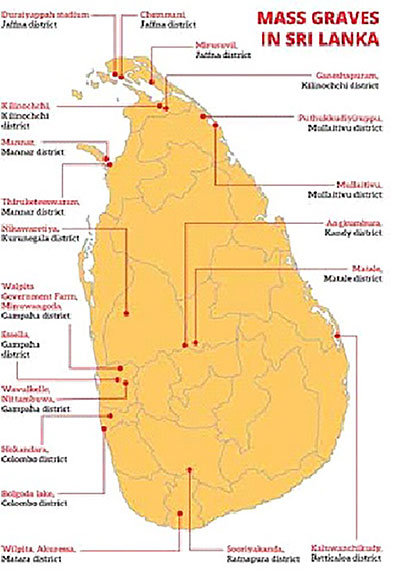

The families impacted by Batalanda gave a moving illustration of the agony they have been going through for all these years in a recent media briefing, in Colombo, organized by the indefatigable human rights activist Brito Fernando. I am going by the extensive feature coverage of the media event and the background to Batalanda written by Kamanthi Wickremesinghe in the Daily Mirror (March 20, 2025). I am also borrowing her graphics for illustration – a photograph of the media briefing and a map of Sri Lanka showing the scattered sites of mass graves – 20 in all.

“We express gratitude to this government for providing the environment to discuss and debate about the contents of this report,” said Brito Fernando, speaking for the families. After addressing Ranil Wickremesinghe’s obfuscations about his involvement, and decrying Chandrika Kumaratunga’s failure to act on the recommendations of the report of the Batalanda Commission of Inquiry she created, Mr. Fernando appealed to the present NPP government to “provide a secure environment where these victims could come out and speak about their experiences,” Nothing more, nothing less, and that is all there is to it.

Whatever anyone else might say, the victims of Batalanda and their survivors have vindicated the NPP government’s decision to formally table the Batalanda Commission Report in parliament. As for their continuing expectations, Brito Fernando went on say, “We have some hopes regarding this government, but they should walk the talk.” Mr. Fernando suggested that the government should co-ordinate with the UNHRC’s Sri Lanka Accountability Project that has become a valuable resource for preserving evidence and documentation involving human rights crimes and violations over many decades. In addition, Mr. Fernando pointed out that the grieving families have not been involved in the ongoing excavations of mass graves, and they are anxious to receive the remains of their dear ones after their identity is confirmed through DNA analyses. Nor has there been any sign of legal action being taken against any of the suspects connected to the mass graves.

Whatever anyone else might say, the victims of Batalanda and their survivors have vindicated the NPP government’s decision to formally table the Batalanda Commission Report in parliament. As for their continuing expectations, Brito Fernando went on say, “We have some hopes regarding this government, but they should walk the talk.” Mr. Fernando suggested that the government should co-ordinate with the UNHRC’s Sri Lanka Accountability Project that has become a valuable resource for preserving evidence and documentation involving human rights crimes and violations over many decades. In addition, Mr. Fernando pointed out that the grieving families have not been involved in the ongoing excavations of mass graves, and they are anxious to receive the remains of their dear ones after their identity is confirmed through DNA analyses. Nor has there been any sign of legal action being taken against any of the suspects connected to the mass graves.

The map included here shows twenty identified mass graves spread among six of the country’s nine provinces. There could be more of them. They are a constant reminder of the ravages that the country suffered through over five decades. They are also a permanent source of pain to those whose missing family members became involuntary tenants in one or another mass grave. The families and communities around these mass graves deserve the same opportunity that the impacted families of Batalanda have been given by the current exposure of the Batalanda Commission Report.

The primary purpose of dealing with past atrocities and the mass graves that hold their victims is to give redress to survivors of victims, tend to their long lasting scars and reengage them as free and full members of the community. Excavation and Recovery, DNA Analysis and Community Engagement have become the three pillars of the recuperation process. Sri Lanka is among nearly a hundred countries that are haunted by mass graves. Many of them have far greater numbers of mass graves assembled over even longer periods. Suffering and memories are not quantitative; but unquantifiable and ineluctable emotions. The UN counts three buried victims as a mass grave. Even a single mass grave is one too many.

To do nothing about them is a moral and social copout at every level of society and in the organization of its state. Normalising the presence of mass graves is never an option for those who live around them and have their family members buried in them. Not for them who have built up over centuries, emotional systems of rituals for parting with their beloved ones. And it should not be so for governments that would otherwise go digging anywhere and everywhere in pseudo-archaeological pursuits.

Mass graves are created because of government actions and actions against governments. But governments come and go, and people in governments and political organizations change from time to time. There is a new government in town with a new generation of members in the Sri Lankan parliament, and it is time that this government revisited the country’s past and started providing even some redress to those who have suffered the most. The families of the Batalanda victims have vindicated the NPP government’s action to officially publicise the Batalanda Commission Report. The government must move on in that direction ignoring the carping of critics who selectively remember only the old JVP’s past.

There is more to what the government can do beyond mass graves. The Batalanda Commission Report is one of reportedly 36 such reports and each Commission has provided its fact findings and recommendations. Hardly any of them have been acted upon – not by the governments that appointed them and not by the governments that came after and created their own commissions. The JVP government must seriously consider creating a one last Commission, a Summary Commission, so to speak, to pull together all the findings and recommendations of previous commissions and identify steps and measures that could be integrated into ongoing initiatives and programs of the government.

The cynical alternative is to throw up one’s hands and do nothing, similar to cynically leaving the mass graves alone and doing nothing about them. The more sinister alternative was what Gotabaya Rajapaksa attempted when he appointed a new Commission of Inquiry to “assess the findings and recommendations” of previous commissions. That attempt was roundly condemned as a witch hunt against political opponents set up under the 1978 Commissions of Inquiry Act that was specifically enacted to enable the targeting political opponents under the guise of an inquiry. Repealing that act should be another consideration for the NPP government.

I am just floating the idea of a Summary Commission as a potential framework to bring positive closure to all the war crimes, emblematic crimes and human rights violations that have been plaguing Sri Lanka for the entire first quarter of this century. It is a political idea befitting the promises of a still new government, and one that would also be a positive fit for the government’s much touted Clean Sri Lanka initiative. For sure, it would be moral cleansing along with physical cleansing. A Summary Commission could also provide a productive forum for addressing the pathetic dysfunctions of the whole law and order system. The NPP government inherited a wholly broken down law and order system from its predecessors, but its critics suddenly see a national security crisis and it is all this government’s fault.

More substantively, a Summary Commission could tap into the resources of the UNHRC in collegial and collaborative ways without the hectoring and adversarial baggage of the past. These must be trying times for the UNHRC, as indeed for all UN agencies, given the full flight of Trumpism in America and its global spill over. Sri Lanka is one of a handful of countries where UNHRC professionals might find some headway for their mission. And the NPP government could be a far more reliable partner than any of its predecessors.

by Rajan Philips