-

Published

Indian woman wrestler Hamida Banu rose to stardom in the 1940s and 50s, when the sport was still a male bastion. Her spectacular feats and larger-than-life persona brought her global fame – but then she disappeared from the scene. BBC Urdu’s Neyaz Farooquee traced Banu’s story to find out what happened to the woman whom many call India’s first professional woman wrestler.

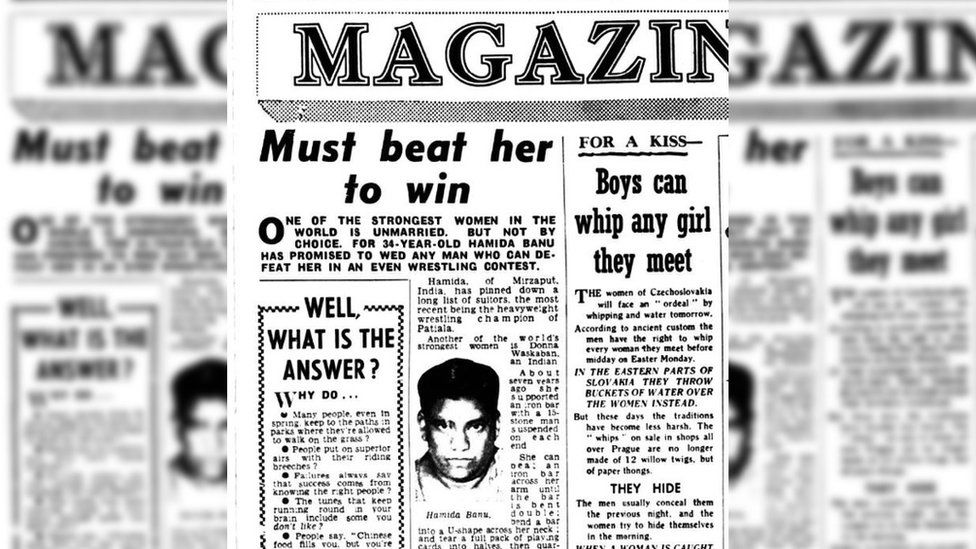

“Beat me in a bout and I’ll marry you.”

That was the unusual challenge that Banu – then in her early 30s – issued to male wrestlers in February 1954, according to news reports from the time.

Soon after the announcement, Banu defeated two male wrestling champions – one from Patiala in northern Punjab state and the other from Kolkata (then Calcutta) in the eastern West Bengal state.

In May, she reached Vadodara (then Baroda) in the western state of Gujarat for her third fight of the year.

Banu’s visit had the city in a frenzy, recalls Vadodara resident Sudhir Parab, who was a child at the time. Her arrival was advertised through banners and posters on lorries and other vehicles, recalls Mr Parab, who later became a feted kho-kho player.

Mr Parab says Banu was supposed to fight Chhote Gama Pahalwan, a wrestler patronised by the Maharajah of Baroda (wrestlers are often called Pahalwan in Hindi). But he withdrew from the fight at the last minute, saying that he wouldn’t fight a woman.

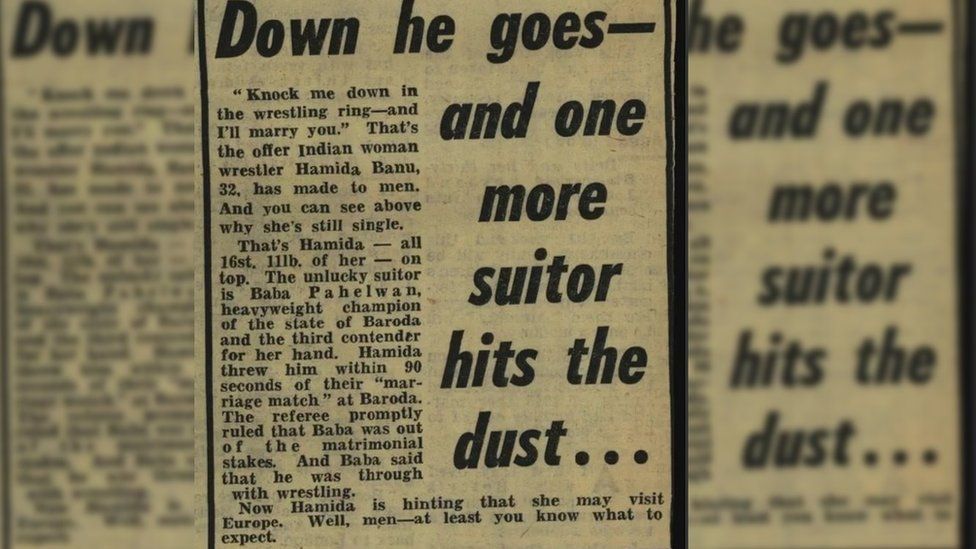

So Banu fought her next challenger, Baba Pahalwan.

“The bout lasted one minute and 34 seconds, when the woman won a fall,” the Associated Press reported on 3 May 1954. “And the referee declared Pahalwan out of her wedding range.”

Banu’s reputation had been in the making for more than a decade by then. In 1944, Bombay Chronicle newspaper reported that about 20,000 people came to a stadium in the city to watch a match between Banu and wrestler Goonga Pahalwan.

The fight was cancelled at the last minute after “impossible” demands by Goonga Pahalwan, which included more money and time to prepare for the match. The enraged crowd vandalised the stadium after the fight was cancelled.

By the time Banu arrived in Baroda, she claimed to have won more than 300 matches.

Newspapers called her the “Amazon of Aligarh”, after the town in Uttar Pradesh state where she lived. A columnist wrote that one look at Banu was enough to send shivers down one’s spine.

Her weight, height, diet all made news. She reportedly weighed 17 stone (108kg) and was 5ft 3in (1.6m) tall. Her daily diet included 5.6 litres of milk, 2.8 litres of soup, 1.8 litres of fruit juice, a fowl, nearly 1kg of mutton and almonds, half a kilo of butter, 6 eggs, two big loaves of bread, and two plates of biryani.

“She sleeps nine hours a day and trains another six,” Reuters noted.

Accounts from Banu’s surviving family members suggest that her strength, combined with the conservative attitudes of the time, made her leave her hometown of Mirzapur in Uttar Pradesh for Aligarh. There, she trained under a local wrestler named Salam Pahalwan.

In a 1987 book, author Maheshwar Dayal wrote that Banu’s fame attracted people from far and wide as she fought several bouts in Uttar Pradesh and Punjab.

“She used to fight exactly like a male wrestler,” he wrote. “However, a few said that Hamida Pahalwan and male wrestlers would make a secret pact, and the opponent would deliberately lose.”

Banu also faced challenges from people who were infuriated by her public performances.

In Maharashtra’s Pune city, a bout with male wrestler Ramchandra Salunke had to be cancelled because the local wrestling federation objected, The Times of India reported.

Another time, Banu was booed and stoned by fans after she defeated a male opponent. The police had to step in and control the crowds, according to the newspaper.

In his book Nation At Play: A History of Sport in India, academic Ronojoy Sen examined how Banu’s presence complicated the sport.

“The blurring of sports and entertainment in these events is illustrated by the fact that Banu’s bout was to be followed by a bout between two wrestlers, one lame and the other blind,” he wrote.

Mr Sen writes that Banu complained to Morarji Desai, then chief minister of Maharashtra state, about an unofficial “ban” on her wrestling bouts. Desai responded that the bouts had not been banned on grounds of her gender “but because of several complaints about the promoters, who were apparently putting up ‘dummies’ to challenge Banu”.

Even as men mocked her accomplishments and questioned her credentials, Urdu feminist writer Qurratulain Hyder paints a different picture of Banu. In her short story Daalan Wala, Hyder writes of her domestic helper Faqira going to watch a wrestling match in Mumbai and returning to say no one had been able to defeat “the lioness”.

According to reports, in 1954, Banu defeated Vera Chistilin, known as Russia’s “female bear,” in less than a minute in a bout in Mumbai. The same year, she announced she would go to Europe to fight wrestlers there.

But not long after these heavily promoted fights, Banu appeared to vanish from the wrestling scene.

This was the point where her life changed, according to accounts from people who knew her.

By then, Banu and Salam Pahalwan had begun travelling regularly between Aligarh, Mumbai, and Kalyan, a town on the outskirts of Mumbai, where they had a dairy business.

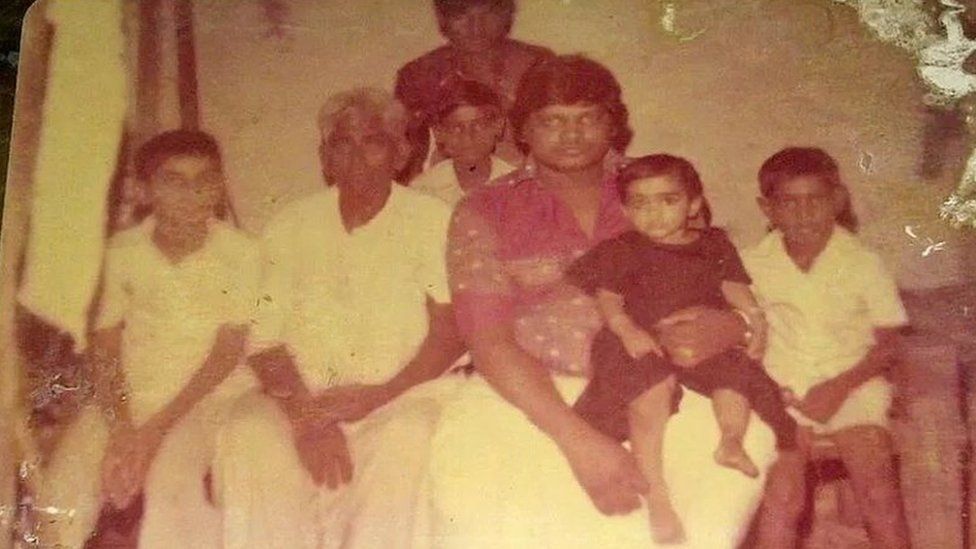

Banu’s grandson, Feroz Shaikh, says Salam Pahalwan, Banu’s coach, did not like the idea of her going to Europe (Mr Shaikh’s father was Banu’s adopted son).

Sahara, Salam Pahalwan’s daughter, says that he had married Banu, whom she considered her stepmother.

But Mr Shaikh, who lived with Banu until her death in 1986, disagrees. “She indeed stayed with him, but never married him,” he says.

“To stop her [from going to Europe], he beat her with sticks, breaking her hands,” says Mr Shaikh.

This account is supported by her neighbour Rahil Khan, who says her legs were also fractured in the attack.

“I remember it well,” he says. “She was unable to stand. It healed later, but she could not walk properly for years without a lathi [stick].”

Sahara, however, maintains that the relationship was cordial.

Eventually, Salam Pahalwan returned to Aligarh while Banu stayed on in Kalyan. Ms Sahara says Banu visited him once in Aligarh when he was on his deathbed.

Banu made a living from selling milk and renting out some buildings. When she ran out of money, she would sell homemade snacks by the roadside.

“Her last days were difficult,” says Mr Shaikh, about the little-known athlete who fought fiercely against the norms of her times.

BBC News India is now on YouTube. Click here to subscribe and watch our documentaries, explainers and features.