FEATURES

UNESCO, the Cultural Triangle and some forunate contacts in Paris

Excerpted from volume ii of the

Sarath Amunugama autobiography

UNESCO’s involvement with the Sri Lankan Cultural Triangle project was a milestone in our mutual relationship. It focused attention on the Sinhala cultural heritage, brought substantial funding from UN agencies to our culture sector, hastened the restoration of ancient monuments and conserved the visual heritage of the country.

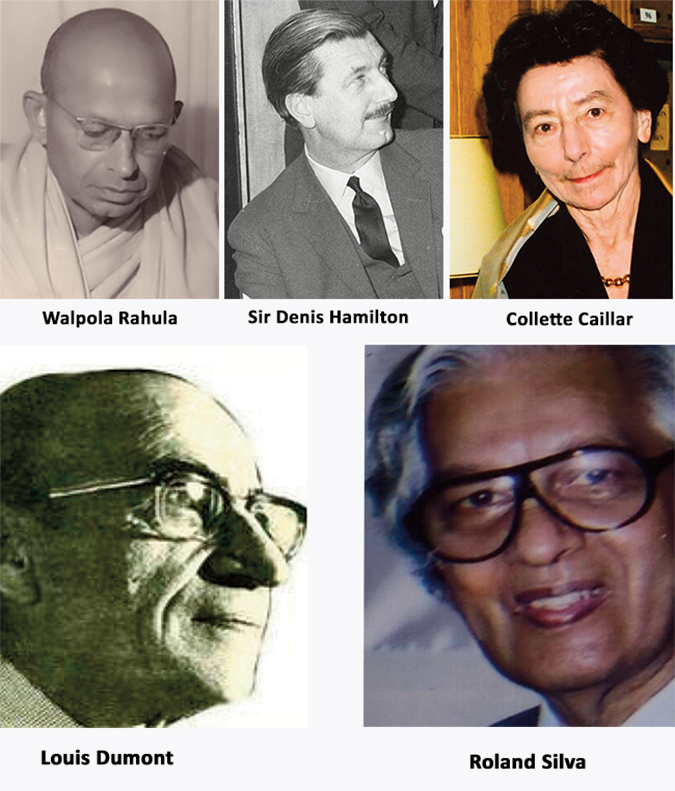

The single most important official in this monumental endeavour was Roland Silva, Commissioner of Archeology and a member of the high level UNESCO committee on cultural conservation. While there was direct UN investment in this project it, also attracted bi-lateral support from countries likeIndia, France and China. This project must be recognized as a singular achievement of the JRJ regime though many tend to overlook it now.

It gave me the opportunity to meet some of the, best international journalists who covered this story when I was the Secretary of the media ministry. The most memorable was my interaction with Sir Denis Hamilton, editor of the London Times and the Chairman of Reuters. Our High Commissioner in London at that time was Noel Wimalasena, a leading Kandy politician and a longtime friend of my father. Wimalasena wrote to me personally stressing the importance of Hamilton’s visit as he was a top class `mandarin’ in the British establishment.

After discussing Wimalasena’s letter with JRJ I decided to personally accompany Denis and his wife Olive on their Sri Lankan tour. Denis Hamilton was a pillar of the British establishment. During the second world war he had served as ADC to General (later, Field Marshall) Montgomery. He was the executor of Monty’s will and the custodian of his papers. Denis was recuperating from a bruising trade union battle with his print workers over changes introduced in the Times which was earlier a hidebound paper of the establishment.

He had to oversee the transfer of its printing works to Canary Wharf on the orders of Rupert Murdoch the owner of the newspaper. It was a bruising battle with the Trade Unions which had sapped his strength. A sackful of the latest literary offerings from London accompanied him on the holiday which began with a week’s relaxation at Bentota Beach hotel. At that time John Keells was the leading hotelier in the country and a tour was arranged through them.

After a week I went to Bentota and with Denis and his wife went on to Kandy. From there we went to Wilpattu circuit bungalow and were lucky to see many leopards. In Wilpattu while sleeping Denis had nightmares about the war and the killings in El Alamein. So we slept late and left for Anuradhapura where the work on the Cultural triangle was to be inaugurated by President JRJ.

It was an impressive ceremony and Denis was also invited to participate, by the UNESCO bigwigs who were overawed by the presence of the Editor of the London Times being on hand to launch the project. We had dinner with JRJ that night. The President after a discussion about his admiration for the Times asked Denis whether he wanted to know anything about the country from him. The answer amused him no end. Denis replied, “No, Sarath has told us everything”.

JRJ laughingly replied, “Surely there must be something more that the President of the country can tell you?” We all laughed and I was amazed at the civility and generosity of all concerned which was a characteristic of their cultured upbringing. It was ti memorable visit by two of the finest and gentlest human being I have ever encountered. On their returning to London I received the following cable; “Back in London and my office first time today. Most grateful thanks to you all from us both for a memorable stay and the friendship formed. Have written to your President and your Minister and looking forward seeing you in the spring; Denis Hamilton”.

When I next went to London they picked me up from my hotel and took me to dinner in the Cafe Royal. It was a wonderful friendship. They are both dead now, Denis from a stomach cancer, but I cherish the memory of them and the happy times we spent together both here and in London. The restoration of the Abhayagiriya or Jetawana dagoba which was inaugurated that day stands as a monument to all those who participated in the Cultural Triangle project which has given new life to our beliefs about the great ancient civilization of Anuradhapura which in its time influenced the whole of Asia and beyond.

It is a solid achievement of the JRJ administration which his successors have not had the imagination to improve upon and publicize to the world. When I was Secretary in charge of tourism I initiated a project with Japanese investors to build a hotel in Anuradhapura for Japanese reli

gious tourists. Land was earmarked for it but after July 1983 there were no takers for this project.

Sorbonne

Both Bhikkus Walpola Rahula and Kosgoda Sobhita had good relations with the Buddhist scholars of the Sorbonne. Among these savants were Andre Bareau and Jean Filliozat who were well renowned scholars of Theravada Buddhism. Most other Buddhist scholars had concerned themselves with Mahayana. This is not surprising since the French colonies in the east [‘Extreme Orient’ in their writings] like Vietnam, Cambodia and Laos were Mahayanistic in religion.

Many of the scholars I associated with in the Sorbonne had spent time in the French colonies as teachers, librarians and archivists. They were Sanskritists since Mahayanist literature was mostly in Sanskrit or in the local languages. The French colonial system encouraged research into archaeology and religion in their outposts.

For instance Andre Malreaux, the celebrated French writer and de Gaulle’s Minister of Culture, lived in China and the French colonies in the ‘Extreme Orient’ and wrote his early novels with an Asian background. Jacques Soustelle, de Gaulle’s first Minister of Information was an archaeologist who wrote the famous book ‘The Voice of Silence’. The Musee Guimet in the Trocadero which displays a fabulous collection of art and sculptures from the Extreme Orient was setup by two French brothers who did business in Cambodia and Vietnam.

One day I was visited in my home by Collette Caillart, the Sanskritist and other scholars from the Extreme Orient Department of the Sorbonne. The French educational bureaucrats had proposed the reduction of funds to their division in order to strengthen Arabic studies for which there was a great demand at that time. My visitors wanted me to intervene with UNESCO and the Sri Lankan government to save their field of study from emasculation.

I did take it up and just like in London University where the Sinhala department was saved, we managed to stave off trouble at least in the short term much to the satisfaction of my friends in academia. While the French University system is generally referred to as being related to the Sorbonne by the general public, in reality after the student riots in the time of de Gaulle it underwent drastic

angel. These reforms which are attributed to de Gaulle’s Prime Minister, and later successor, Georges Pompidou broke up the University of Paris into five successor Universities.

Thus students were attached to one of the five new Universities of Paris. This allowed for the absorption of a larger number of students and teachers who were earlier deprived of a stable engagement and were therefore violence prone. After the Pompidou reforms there have been no student riots for over half a century. Rahula and Sobhita were Sorbonne professors who with UNESCO and the CNRS formed an admired and respected academia on Buddhist studies which made Paris a center of interest in the Western world.

This was a far from the Sinhala Buddhist Vihare which tended to cater to the immediate ritualistic needs of the growing Sinhala expatriate community in Paris, especially their womenfolk and children. It a link in a chain of similar temples in all parts of Western Europe and the US. The monks themselves had established networks which allowed them to travel all over Europe and the US. So for every celebration like Wesak we played host several young monks who went sightseeing in Paris.

They we entertained by their kinsmen from their native villages who we now well settled in Paris. Time and again I was introduced to monks who had come from my friends’ respective villages. Both Rahula and Sobhita gave them a wide berth. One unfortunate aspect was that many of these young monks did not bother to learn western languages or the manner of delivering sermons that their seniors practiced. They were content to function as the did in their villages and often created conflicts in the expatriated community.

Of course this was not true of a few young monks who studied the dhamma and were held in high regard both by their worshippers and the academic community. However the respect that Rahula and Sobhita earned through their erudition has been lost and monks get by with local community services and seeking political patronage from home – a tendency which would have, horrified Walpola Rahula and those Sorbonne savants who did so much to profile Buddhism in Paris as an outstanding philosophic quest. Of late hardly any new works on Theravada has come from France which was once its European epicenter.

Ecole Des Hautes Etudes En Sciences Sociale

Another aspect of the French higher educational system was the establishment of ‘Ecoles’ of Advanced Studies. For the social sciences the most prestigious was the EHESS which was located in Boulevard Raspail. The Director of the EHESS when I enrolled in it for a doctorate in social anthropology was Louis Dumont who was one of the world’s outstanding anthropologists specializing in South Asian society and religion. The only other world class French anthropologist at that time was Claude Levi Strauss who was teaching at the College de France. By a strange coincidence I had become a friend of Louis Dumont even before I came to Paris and the EHESS.

When I was the Director of Information in Sri Lanka in about 1970, Dumont walked into my office in Colombo with a request. He was on an Asian tour on behalf of the fledgling EHESS, to collect fugitive material for its library in Paris. Since I was the officer responsible for the Government Publications Bureau he needed my consent to buy a stock of publications available in the Bureau. Dumont must have got a pleasant shock when I immediately recognized him as one of my academic heroes and quickly arranged to have the books sold to him.

It must have been a busy day for our sleepy Publications Bureau. He was staying at the Samudra Hotel and I invited him for drinks and dinner. We had a pleasant evening discussing academic matters and particularly talking about my teacher Tambiah whose essay on kinship and marriage was used by Dumont in support of his theory of ‘marriage alliances’. We became friends and I would visit him in his small apartment in Rue de Bac in the Latin Quarter when visiting Paris for UNESCO meetings.

He supported my application to register for a doctorate at his ‘Ecole’ and exempted me from some preliminary steps as I had a Master of Arts degree from the University of Regina. He helped me to get around the academic bureaucracy of the EHESS. When I met him last in his apartment he had retired and was getting ready to leave for his country residence away from Paris. Before that he introduced me to his chief disciple Jean-Claude Galay, a brilliant young anthropologist, who was to be my supervisor, together with Eric Meyer, the economic historian whose area of specialization was Sri Lanka.

My three year academic odyssey at the EHESS with its gathering of brilliant Young scholars of South Asia, is an unforgettable and pleasant episode in my life. By this time my family had arrived in Paris and I moved house from north Paris to Rue Jean Daudin in the most fashionable district of Paris which was only a stone’s throw away from my office in Rue Miollis. It saved me hours of travel time to office and EHESS.

My friend Dilip Padgoankar and wife Lotika were going back to India and their flat fell vacant. Dilip – a ‘bon vivant’ who later became the Editor of the Times of India and advisor to the Indian Government on Kashmir, had chosen well. As M’Bow’s media spokesman he was on call all, the time and had to live close to his boss’s office. Thanks to his recommendation I managed to secure that flat. It was spacious,,- enough to accommodate me, my wife and two children, and was close to good restaurants, cinemas and theatres.

Many children of UNESCO staff lived in the vicinity and they all went to the same schools so that the neighborhood was congenial. For instance, Varuni had a friend who was the daughter of a sister of the Shah of Iran who was in exile, living in a mansion close by. Another friend Mohammed Musa was the son of M’Bow’s advisor from Nigeria. Ramanika’s best friend was the daughter of a senior Indian professional in the science sector of UNESCO. All in all it was a stress free life wherein I could easily handle my official duties as well as academic pursuits with ease. From our Metro station Segur, it took me less than ten minutes to get to EHESS on the Boulevard Raspail.