FEATURES

1943 and all that : Some reflections on history

By Uditha Devapriya

1943 is important to this county for at least four reasons. It was in that year that C. W. W. Kannangara tabled the findings of the Report of the Special Committee on Education, which led to a free education scheme that continues to benefit every child, regardless of his or her class background, today. It was also in that year that the splinter group of the Lanka Sama Samaja Party, led by the likes of S. A. Wickramasinghe, formed the Communist Party. The CPSL’s manifesto was published in Kesari, the radical magazine founded by Lionel Wendt. It was in 1943 that Wendt died, but not before he founded the 43 Group, the most promising radical and avant-garde cultural movement ever formed in Sri Lanka.

Free education, the Communist Party, Lionel Wendt’s passing, and the 43 Group. Four disparate names and events, connected by the slenderest thread, yet one underlying a pivotal transformation, more pivotal than 1948, the year of our independence. What are we to make of these incidents, and how do they reflect on our present moment? 80 years on, and 75 years on after independence, do we look back with pride or sadness, with the sort of bittersweet nostalgia that our history has warranted? One cannot deny that these events exuded much promise and potential, that they paved the way for the further emancipation and modernisation of our country. Yet did we ever take the initiative?

To answer this is to ask how exactly these projects, disparately linked to each other as they were, strived to modernise our country. To ask that, in turn, is to ask in what way Sri Lanka was modernised, or not modernised, prior to them. Sri Lanka’s transformation into a classic plantation enclave in the 19th century more or less entrenched a colonial bourgeoisie who remained Westernised in outlook, but who associated Westernisation with modernisation to such an extent that while emulating in every possible way the habits and customs of their colonial overlords, they remained staunchly conservative, prejudiced, and bigoted in every other aspect. By the end of the century, the plantation economy and the education system, as well as the civil service, had succeeded in creating a class of Ceylonese who approximated much better to Macaulay’s vision than did their Indian counterparts.

By 1931 three developments had made it impossible for this status quo to continue: the Buddhist Revival, the extension of the franchise, and a series of laws making education more accessible to the masses. Four years after the extension of the suffrage, an event all the more remarkable given that it predated the granting of the vote in the Jewel in the Crown, India, a group of Western educated radicals, lacking a commitment to a specific left-wing ideology but unified in their demand for the overthrow of the colonial order, founded the Lanka Sama Samaja Party. The manifesto of the party, as the LSSP’s chief theoretician Hector Abhayavardhana noted decades later, reflected not so much a commitment to partisan left-wing ideology as a practical attempt to address concerns relevant to the masses of Sri Lanka, such as the use of swabasha – Sinhala and Tamil – in the police and the courts.

The Buddhist Revival’s contribution was no less significant. Until the last quarter of the 19th century Buddhists had been debarred from government service: to enter it they had to convert to Christianity, specifically Anglicanism. There are, of course, debates surrounding the extent to which Anglicanism permeated the British State in Ceylon.

By the tail-end of the 19th century it was clear that Anglican Christianity could survive in Ceylon because its official sponsor happened to be the British government. Even there the relationship was complex: despite its avowed preference for Christianity, the British State, on more than one occasion, had to balance competing Christian missionary interests, and had to take care not to be seen as privileging one group over all others, particularly in education.

Like every other revival movement, the Buddhist Revival had its progressive and regressive sides. There is, however, no way of distinguishing between the two. H. L. Seneviratne has tried to do so in The Work of Kings, but I remain unconvinced by the divisions he highlights for reasons I will delve into in another essay. Without entering anthropological territory too much here, all I will say is that the “modernist” and “ritualist” sides of the Buddhist Revival were often represented and promoted by the same people.

The same figures advocating the de-ritualising and urbanisation of Buddhism, for instance, claimed to present a pristine and traditional interpretation of Buddhism no less cultist than the Buddhism they critiqued and sought to make more relevant to the up-and-coming urban bourgeoisie. I can cite no better example of this than D. S. Senanayake, a patron of the Revival who let himself be projected as a successor to the kings of Anuradhapura, as Minister of Agriculture, by embarking on one ambitious irrigation project after another. The same can be said of that other seminal UNP leader, J. R. Jayewardene, who could in the 1930s promote a “rational” reading of Buddhism and 40 years later conduct a campaign for a Dharmista Samajaya.

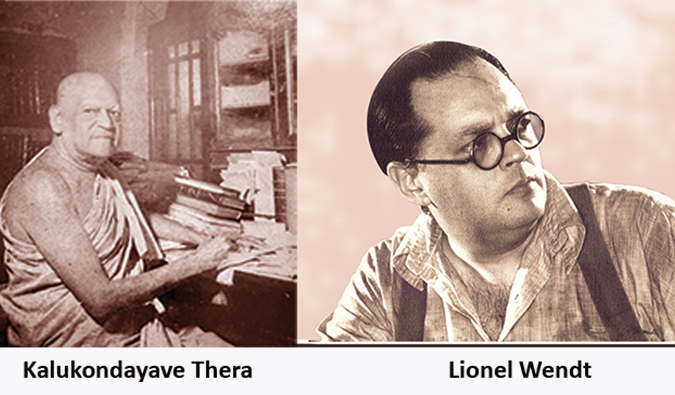

Perhaps the only clear difference between the Buddhist Revival and the other two major developments highlighted above – that is, the widening of the franchise and education reforms – is that the latter two provoked ordinary people, and a generation of left-wing radicals, to question the foundation of the country’s ties to the British Empire. Here we are indebted to Professor Seneviratne’s research, because he very astutely notes how the most conservative of Buddhist monks from this period, including the great Kalukondayave Thera, saw no contradiction between their attempts at regenerating the rural economy and their subservience to a British colonial order.

I think the same can be said of almost all nationalist figures from that time: their concern was not so much achieving independence as ensuring a bigger, higher place for their collective. This is how and why the Buddhist Revival could bring together the political elites of the day: because it was conducive to their strategy of wresting political reforms from the colonial order by working with the latter.

By the 1930s and 1940s the Buddhist Revival had been co-opted by the colonial bourgeoisie, or specifically a section within it that had come out into the open in the early 20th century through such experimental initiatives as the Temperance Movement. After this bourgeoisie, which harboured all the ideals and pretensions of a modernising class, took over from the old order, and helped form the Ceylon National Congress, they became as conservative and non-modernising as their forebearers: a process brilliantly charted by Kumari Jayawardena in the last few chapters of Nobodies to Somebodies. There was, of course, a section within the Revival which agitated against this state of affairs, represented by Anagarika Dharmapala. Yet by and large, the rationalist, anti-ritualist reading of Buddhism promoted by the Revival had been adopted by the newly converted Buddhist bourgeoisie as their creed.

Despite the somewhat progressive inclination of the Ceylon National Congress – a group which later admitted the Communist Party – one could not expect a truly emancipatory project from it. The extension of the suffrage and the education reforms from this period made it difficult if not impossible for the CNC to sustain such a project, much less carry it through. Meanwhile the Buddhist Revival generated its share of paradoxes and convulsions, paving the way for a split between a conservative clergy who were content to work with the political establishment and an activist clergy who rebelled against that establishment and shifted to the Left. Against such a backdrop, only the Left could be expected to see through the kind of anti-imperialist project that the new colonial bourgeoisie and petty bourgeoisie, given their conservative roots, and the Buddhist Revival, given the co-option of a section in it by that conservative bourgeoisie and petty bourgeoisie, could not.

It is in light of these developments that one should examine and evaluate the three major events of 1943, a year which, as I mentioned at the beginning, was in many ways more pivotal and transformative than 1948. The institutionalisation of free education, despite the opposition of many high-ranking CNC members, including D. S. Senanayake; the founding of the Communist Party, which was admitted to the CNC, an incident that compelled the arch-conservative Senanayake to leave that body and form the UNP; and the founding of the 43 Group, which housed many radically minded avant-garde artists, not least of whom Lionel Wendt, who published the Communist Party’s manifesto in Kesari, all owed their radical and liberal initiative to the shift to the Left which had been signalled by the granting of universal suffrage and the extension of school facilities. These, more than any other development, had the potential of pushing Sri Lanka towards a more radical, modernist course. Unfortunately, for obvious reasons, this course was one which Sri Lanka would not take. In that sense, 1943 signalled the demise of its own radical potential – with the death of Wendt.

The writer is an international relations analyst, researcher, and columnist who can be reached at udakdev1

@gmail.com.