Dmitry Mishov, Russian airman who defected, gives BBC interview

-

Published

A military defector who fled Russia on foot has given a rare interview to the BBC, in which he paints a picture of an army suffering heavy losses and experiencing low morale.

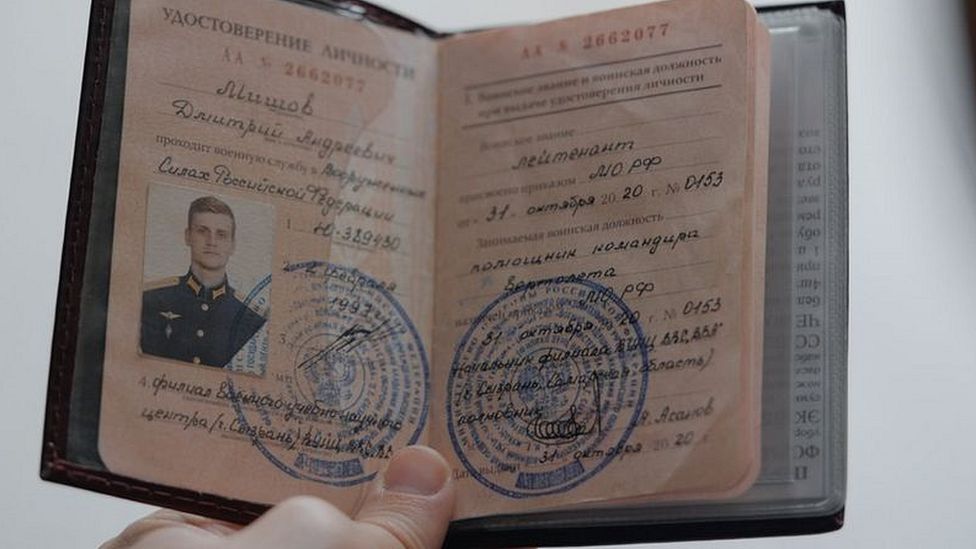

Lieutenant Dmitry Mishov, a 26-year-old airman, handed himself into the Lithuanian authorities, seeking political asylum.

Dmitry said escaping from Russia in such dramatic fashion, with a small rucksack on his back, was his last resort.

He is among a small handful of known cases of serving military officers fleeing the country to avoid being sent to Ukraine to fight – and the only case of a serving airman that the BBC knows of.

Seeking a way out

Dmitry, an attack helicopter navigator, was based in the Pskov region, in north-western Russia. When the aircraft started to be prepared for combat, Dmitry sensed a real war was coming, not just drills.

He tried to leave the air force in January 2022 but his paperwork had not gone through by the time Russia invaded Ukraine on 24 February. He was sent to Belarus where he flew helicopters delivering military cargo.

Dmitry says he never went to Ukraine. We cannot verify this part of his story but his documents appear to be genuine and many of his statements match what we know from other sources.

In April 2022 he returned to his base in Russia where he hoped to continue his decommissioning. It was a lengthy process which was close to completion – but in September 2022 President Putin announced partial military mobilisation. He was told he would not be allowed to leave the army.

He knew that sooner or later he would be sent to Ukraine and started looking for ways to avoid it.

“I am a military officer, my duty is to protect my country from aggression. I don’t have to become an accomplice in a crime. No one explained to us why this war started, why we had to attack Ukrainians and destroy their cities?”

He describes the mood in the army as mixed. Some men support the war, he says, some are dead against it. Very few believe they are fighting to protect Russia from real danger. This has long been the official narrative – that Moscow was forced to resort to a “special military operation” to prevent an attack against Russia.

Overwhelming and common, according to Mishov, is unhappiness with low salaries.

He says experienced air force officers are still paid their pre-war contract salary of up to 90,000 roubles (£865, $1090). This is while new recruits are being tempted into the army with 204,000 roubles (£1960, $2465) as part of an official and publicly advertised campaign.

Dmitry says that while attitudes towards Ukraine may vary, no one in the army believes official reports about things going well at the front or about low casualties.

“In the military no one believes the authorities. They can see what is really happening. They are not some civilians in front of the telly. The military do not believe official reports, because they are simply not true.”

He says that while in the early days of the war the Russian command was claiming no casualties or losses of kit, he personally knew some of those who had been killed.

Before the war his unit had between 40 and 50 aircraft. In the first few days after the start of the Russian invasion, six had been shot down and three destroyed on the ground.

Russian authorities rarely report military casualties. Last September, Defence Minister Sergei Shoigu said Russia had lost around 6,000 men, a figure most analysts, including pro-Kremlin military bloggers considered an underestimate.

In the most recent instalment of a research project identifying Russian servicemen killed in the war in Ukraine, BBC Russian’s Olga Ivshina compiled a list of 25,000 names and in many cases ranks of soldiers and officers. Real figures, including those missing in action, she believes, are much higher.

Dmitry describes losses among military air crews as extremely high. This matches findings in an investigation Olga Ivshina has been conducting which found that Russia lost hundreds of highly skilled servicemen, including pilots and technicians, whose training is time-consuming and costly.

“Now they can replace the helicopters, but there are not enough pilots,” Dmitry says. “If we compare this to the war in Afghanistan in the 1980s, we know that the Soviet Union lost 333 helicopters there. I believe that we’ve experienced the same losses in one year.”

The great escape

In January this year, Dmitry was told he was going to be sent “on a mission”.

Realising that it could mean only one thing – going to Ukraine – he resorted to a suicide attempt. He hoped that this would lead to his decommissioning on health grounds. But it did not.

While he was recovering in hospital, he read an article about a 27-year ex-police officer from the Pskov region who had successfully escaped to Latvia. Dmitry decided to follow his example.

“I was not refusing to serve in the army as such. I would serve my country if it faced a real threat. I was only refusing to be an accomplice in a crime.

“Had I boarded that helicopter, I would have taken the lives of several dozen people, at the very least. I didn’t want to do that. Ukrainians are not our enemy.”

Dmitry searched for help on Telegram channels to plot a route through the woods on the EU border. He packed as light as he could.

He says walking through the woods was terrifying as he feared being stopped by border guards.

“Had they arrested me, I could have gone to prison for a long time.”

He says at one point a flare launched somewhere close to him and then another one. He panicked that this were border guards coming after him and started running.

“I couldn’t see where I was going, my thoughts were in disarray.”

He came to a wire fence and climbed over it. Soon he knew he made it.

“I could finally breathe freely.”

Dmitry assumes the Russian authorities will start a criminal case against him. But he believes many of his army comrades will understand his motivation.

Some had even advised him to try and hide in Russia, but he thinks even in a country that vast he would not have escaped being found and punished for desertion.

He does not know what will happen to him next.

But Dmitry says he prefers to try and build a new life in the EU than be on tenterhooks at home.

Edited by Kateryna Khinkulova.