Controversial land sale puts Jerusalem Armenians on edge

-

Published

Wearing peaked black headdresses and long robes, a procession of Armenian priests is led along the stone streets of Jerusalem’s Old City by two suited men in felt tarboosh hats with ceremonial walking sticks.

Quietly, apart from the tapping of the sticks, they file into the Church of the Holy Sepulchre for prayers.

Nowadays, Jerusalem is at the core of the conflict between Israelis and Palestinians. But Armenians have been here since the 4th Century, when their country was the first to adopt Christianity as a national religion.

They have a share in the Old City’s holiest Christian sites and their own quarter tucked away in its south-western corner, home to some 2,000 Armenians.

But now the community here feels under threat because of a murky real estate deal by its own Church leaders. Amid angry protests, the Armenian patriarch has hidden himself away and a disgraced priest, who denies any wrongdoing, has fled to California.

“It’s like a puzzle. I mean, we are trying to know what happened, when it happened, and how,” explains community activist Hagop Djernazian.

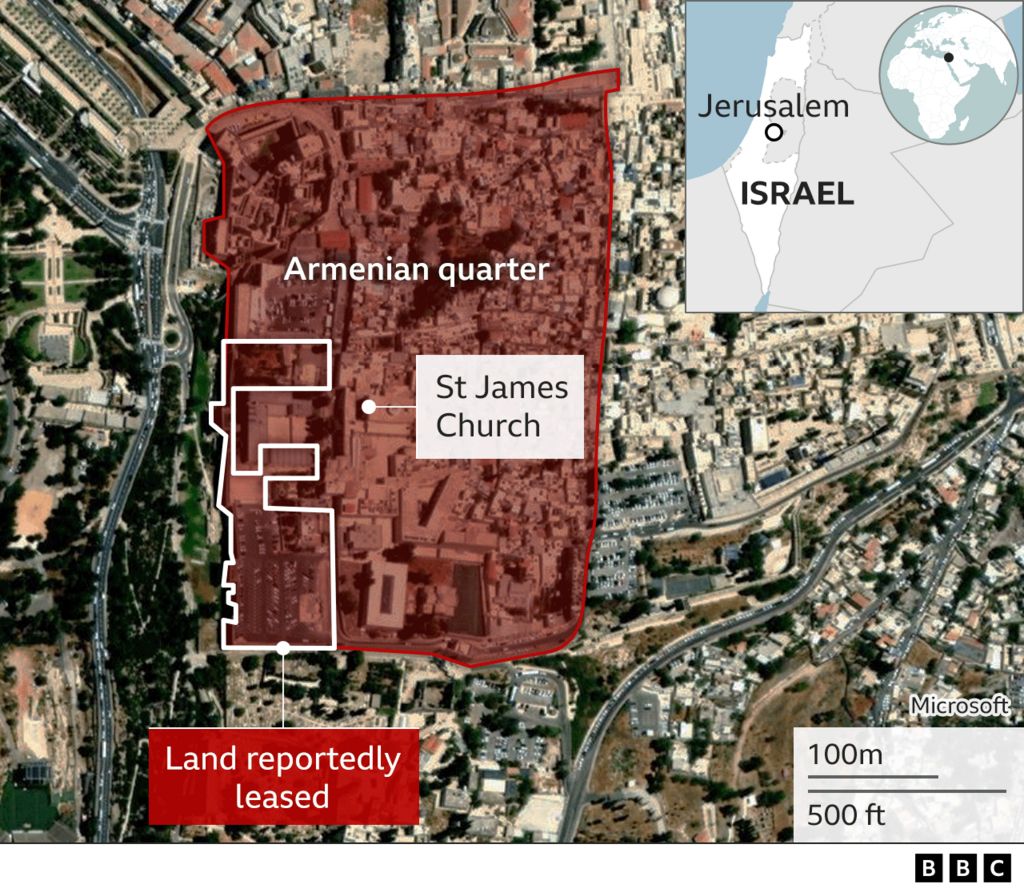

What has emerged is that some 25% of the Armenian Quarter has been sold on a 99-year lease to a mysterious Jewish Australian businessman for a luxury development.

The land includes a large car parking area – one of the few areas of open land inside the Old City walls – which his company has already taken over. Many Armenians had hoped the site could be used to build affordable housing for young couples from their tiny, shrinking community.

According to plans seen unofficially by Hagop and others, an Ottoman-era building housing five Armenian households, a restaurant, shops and the seminary are all part of the sell-off. Many fear this could affect the viability of living in the quarter in the long-term.

But the controversy extends far more widely.

“It is historical land that we have had for 700 years. Losing it with one signature will affect our cultural daily life, but it will also change the picture of Jerusalem,” Hagop says. “It will change the status quo, the entire mosaic of Jerusalem.”

Changing character

As the Orthodox Easter celebrations took place in April, panic was spreading among Armenians. The Armenian Patriarch, Nourhan Manougian, admitted that he had signed away the land but said he had been deceived by a local priest who worked for him.

That priest was defrocked and later there were heated scenes as he was banished from the Armenian Quarter, escorted away under Israeli police protection as residents yelled out “traitor”.

Recently, many Armenians have been joining weekly protests, linking arms and singing nationalistic songs below the window of the patriarch who now stays cloistered in his rooms at the convent. They demand that he revokes the land deal.

Amid a recent rise in attacks by extremist Jews targeting Christians in Jerusalem, some Armenians see the sale as an act of self-inflicted harm on the Christian presence here.

“The look of the city, its character is changing very much,” says Arda, who lives in the Old City and complains that religious nationalists already feel emboldened by the drift of Israeli politics.

“Priests walking in the streets find settlers spitting at them, people say they don’t want to see Christmas trees in the city, and restaurants are being attacked for no reason. It’s all going in a certain direction.”

Israel captured East Jerusalem – including the Old City – from Jordan in the 1967 Middle East War and went on to occupy and annex it in a move that is not recognised internationally. In the decades since, it has been at the heart of the Israel-Palestinian conflict, claimed by both sides as their capital. Plots of land here are fiercely fought over.

There is a reminder of that near to the Armenian Quarter, at Jaffa Gate – the iconic entrance to the Christian Quarter.

Here, two landmark hotels, run by Palestinians, were secretly sold to foreign firms acting as fronts for a radical Jewish settler group. The Greek Orthodox Church lost a two-decade-long battle to cancel the deal in the Israeli courts and last year settlers moved into part of one of the hotels.

Armenian elders say that in the past, there have been frequent approaches by settlers wanting to buy land in their quarter and increase the Jewish presence in East Jerusalem. The Armenian Quarter is located next to the Jewish one, which makes it especially desirable.

However, a spokesman for the settler group which bought the Jaffa Gate properties told the BBC he had no knowledge of the Armenian land sale.

Patriarch sanctioned

Meanwhile, in interviews in the US, the cast-out priest, Baret Yeretsian, has dismissed the idea that the buyer of the land lease – named as Danny Rothman but also Daniel Rubinstein in some documents – is driven by ideology.

Nevertheless, Palestinian Christian leaders say the sale has political implications.

“It undermines any future political solution to Jerusalem,” says Dimitri Diliani, president of the National Christian Coalition of the Holy Land. “According to international law, it’s on occupied land that is subject to negotiations and this kind of reinforces the illegal settler presence in Palestinian East Jerusalem.”

He believes that “the diversity” of Jerusalem will also be badly affected.

Highlighting the significance of the Armenian Church’s actions, both the Palestinian President and Jordan’s King Abdullah II – custodian of Jerusalem’s Christian holy sites – have suspended their recognition of the patriarch. This affects his ability to attend ceremonies and sign off on official church business.

Israel’s foreign ministry has said it is aware of the Armenian patriarch’s deal but due to the political sensitivity it refrains from commenting on it.

Meanwhile, in the walled courtyards of St James Convent – which has been home to many Armenian families since the 1948 Arab-Israeli War and has its own clubs, school, library and even a football pitch – the talk nowadays is about little else.

Relations have been strained between the residents and clergy members, who act here as the religious and civil authority. On Friday, dozens of Armenian Jerusalemites gathered to hear from a group of international Armenian lawyers who have been visiting and have agreed to draw up recommendations on how to handle the case.

Nearby, in his ceramics shop, Garo Sandrouni paints glaze onto an ornately decorated bowl wondering what the future will bring.

He is from one of the families that brought the colourful tradition of Armenian pottery to Jerusalem a century ago, when they fled from what is widely seen as a genocide by the Turks.

He says that Armenians historically donated money to buy land in this holy city – their spiritual homeland – and that the Church has no right to sell it.

“This is what makes us angry. These lands belong to the Armenian nation. They don’t belong to the Armenian patriarchate of Jerusalem,” he tells me.

“The Armenian patriarchate of Jerusalem has to take care of these lands to keep them to preserve them, to protect them.”