FEATURES

Queen’s Speech leak and a threat of resignation followed by retirement

(Excerpted from Memoirs of a Cabinet Secretary by BP Peiris)

With prorogation, began my holiday task – the preparation of the Queen’s Speech. On this occasion, I had all the time I needed for thinking and I decided upon an entirely new technique in drafting. In order to prevent Ministers tinkering with my draft and, for prestige reasons of their own, insert a paragraph here and a paragraph there, I decided to include in the Speech everything that could possibly be included and ask the Ministers to delete what they did not want. My scheme worked.

When a Minister said “I’d like to say something about the Panchen Lama and the headhunters of Borneo”, I would say “That’s there at pages six and seven”. But my draft, which extended to twelve pages, was far too long and had to be drastically pruned. This was done at four separate meetings. At each meeting I took back all the copies I had circulated, put one in my office file for purposes of record and the rest in the office incinerator.

At the fourth meeting, the final draft had been reduced to a sizable four pages, and on the next day, nearly 20 points from the Speech leaked to the Press, an unprecedented thing. Naturally, the Prime Minister was angry. That feeling of suspicion about the other fellow still prevailed among the Ministers. In this atmosphere, the Prime Minister asked at the next meeting “How could this have happened? Mr Peiris gave you the copies and took them all back every time. This can’t be a leak through the Ministers. It can only be a leak from the Cabinet Office”.

Trembling with anger, I retorted, “Madam, your remark shows that you have serious doubts about my integrity, in which case I am prepared to leave this office and the public service immediately”. She said she was not referring to me. The leak could have taken place through one of my clerks. I replied that this work had always been entrusted to my most senior clerks, that I was not used to passing blame to my subordinates, and that I took the entire responsibility upon myself.

I added “Madam, now that you have raised this matter, I wish to say, with sorrow, something that has been boiling within me for the last few years. This is not the first leak to the Press. Our decisions have been appearing regularly in the Press after our meetings and three top executives in the Press have given me the names of five Ministers, now present in this room, who are the sources of their information. Please don’t embarrass me by asking me for their names”.

I expected a sort of “How dare you?” from one of the Ministers. No one spoke and Madam proceeded with the Agenda. We were four brothers, three of whom had taken to Government service and one to planting. During my last years as a public servant, the three of us who were drawing the Queen’s shilling were the Heads of our respective Departments. I, a lawyer, .was Secretary to the Cabinet; brother S. W., an engineer, was General Manager of the Government Electrical Undertakings; and brother G. S., the youngest, was Director-General of External Affairs. This, I believe, is unique in the history of our public service.

The Cabinet at this time decided that Sinhala as the Official language should be made “fully effective” in the administration from January 1, 1964. Accounts were to be kept in the official language which I did not understand. I was required, as Head of Department, to certify the correctness of my Appropriation Account which went to the Auditor-General and the Public Accounts Committee of the House of Representatives. After 27 years of honourable public service, twice honoured by the Sovereign, once only surcharged by audit in a sum of six cents for overpaying my dear friend Harrry Wendt on a travelling claim for going from the Legal Draftsman’s Chambers to the State Council, I was not prepared to sign an important financial document of the Government like the Appropriation Account, in a language I did not understand.

I addressed the following letter to the Governor-General after apprising the Prime Minister of my intention. She tried her best to persuade me to change my mind, but understood when I told her that my conscience would be troubling me when I knew that I was continuing to bat after I had been out according to the M. C. C. Rules:

To His Excellency the Governor-General

Your Excellency,

My term of office as Secretary to the Cabinet was extended by Your Excellency on the recommendation of the Hon. the Prime Minister under section 50 of the Ceylon (Constitution) Order in Council until March 29,1964, when I shall reach the age of fifty-six years. In the meantime, the Cabinet has decided that Sinhala should be made fully effective in the administration by January 1, 1964.

I am not proficient in Sinhala and I will therefore be unable, as the Chief Accounting Officer of this Department, to read my Votes Ledger, Petty Cash Ledger, Vouchers and other financial documents which will be in Sinhala. I will therefore be unable to give my certificate to the Auditor-General that my Appropriation Account is in order.

I have also undertaken to give Your Excellency at least three months notice before my retirement.

I have the honour, therefore, to request Your Excellency to be so good as to allow me to retire from my office on December 31,1963, and to allow me leave preparatory to retirement which my office informs me is 37 days, and to relieve me of my duties as Secretary to the Cabinet on November 16, 1963.

As the appointment of my successor is in Your Excellency’s hands I have no doubt that the Hon. Prime Minister will make a recommendation in due course.

I am,

Your Excellency’s obedient servant,

B. P. Peiris.

Secretary to the Cabinet.

When the news of my impending retirement got out, the following appeared in the “Daily News” under the nom de plume ‘w’:

“In a Parliamentary democracy, where party politics in comparatively new and tends to colour the judgment of officials close to the seat of political power, B. P. Peiris, as Secretary to the Cabinet, has been unique. He had no political affinities whatsoever.

“D.S. Senanayake, Dudley Senanayake, Sir John Kotelawala, S.W.R.D. Bandaranaike, W. Dahanayake, again Dudley Senanayake, and finally, Mrs Sirimavo Bandaranaike – they were all, to him, Prime Ministers of Ceylon whose interests he served as long as they were, or are, Prime Minister. He had nothing to do with their politics but had everything to do with the art of Cabinet Government which they were called upon to practise.

“As Assistant Secretary first, and later as Secretary to the Cabinet, he was loyal to each of them, while each of them functioned as Heads of Government.

“No man had a better opportunity to compare and contrast the strength and weaknesses of the Prime Ministers of Ceylon than B. P. Peiris. But he never compared and contrasted because he was always conscious of his obligations as the chief executive of the citadel of Government. He was no uneducated menial, thrown up by patronage, to high office. He came to serve in the Cabinet room from the Legal Draftsman’s Department.

“A graduate of the University of London and a Barrister-at-Law of Lincoln’s Inn, and with experience in legal draftsmanship he was a worthy successor to T. D. Perera and A. G. Ranasinha who were Secretaries to the Cabinet before him. And with many years’ experience of Cabinet Government, he came to be regarded as a trusted adviser at Cabinet meetings. During his long career, B. P. Peiris has maintained the high standards of honourable conduct, never using his position to secure undue advantage for himself or for any others connected to him by ties of relationship or friendship. In fact, it was on a matter of principle that he has sent in his retirement papers.

“Under the new ‘Sinhala Only’ policy, as head of the Cabinet Office, he will have, he argued within himself, to sign the annual estimates of expenditure prepared in Sinhala. Could he, not knowing Sinhala, adecuately, sip a document which he did not understand but for which he would be responsible? Intellectual honesty, therefore, demanded that he should go away.

“That is one inside story worthy of record during a period of our Island history where intellectual honesty is as difficult to locate as a nail in a paddy barn.

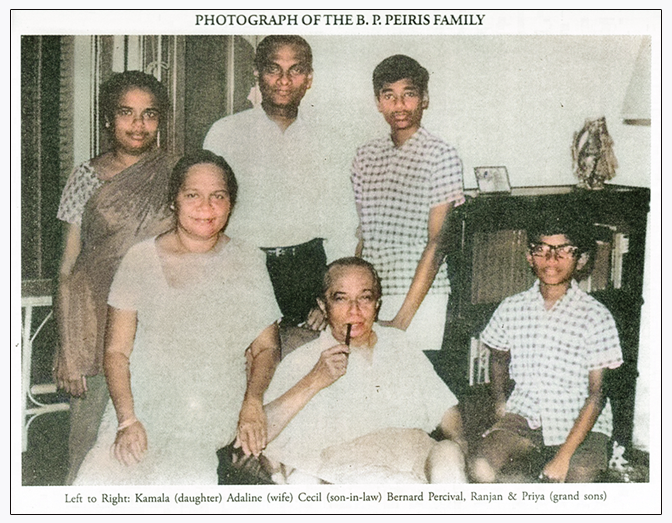

“Choosing to live a secluded life owing to the office he held, B. P. Peiris had few friends, save a few cronies who were, like him, interested in music. To him, the joy of living always centred round his piano, and he also had the good fortune to have a daughter and a son-in-law and a tiny tot of a grandson who played other instruments while he presided at the piano.

Peiris was indeed a ‘character’ in the public service. Long before politicians for their own ends made a fetish of the common man, Peiris, the Barrister-at-Law of Lincoln’s Inn, the man who spoke and read

naughty French novels and loved good music, was a dearly beloved comrade of the arachchies and the peons who worked for him. Indeed, those who will miss him in office will include, not only Cabinet Ministers of the land, but Mr Common Man of the Cabinet Office.”

I was to go on leave on November 14, 1963, and retire on December 31 of the same year. Before my retirement, I mentioned to my friend and colleague at the Bar, Sam P. C. Fernando, Minister of Justice, that I had been, for 17 years a Justice of the Peace Ex Officio for the judicial district of Colombo, that the appointment would lapse on my retirement and that it would be an honour to me if I could continue to hold the office in my individual capacity. People in the area had got to know me and made use of my services. A few days later, I received my letter of appointment as a Justice of the Peace for all the judicial districts of the Island.

November 13, 1963, was my last working day. The Cabinet sat for a group photograph with me and entertained me at lunch in the Senate. The Prime Minister in a farewell speech spoke of my loyalty, honesty and integrity and wished me happiness in my retirement.

In spite of the high cost of living, my office staff entertained me at a farewell lunch at the Grand Oriental Hotel.

And so ended my career as Secretary to the Cabinet.

(Concluded)