FEATURES

Finding the Rural in the Urban

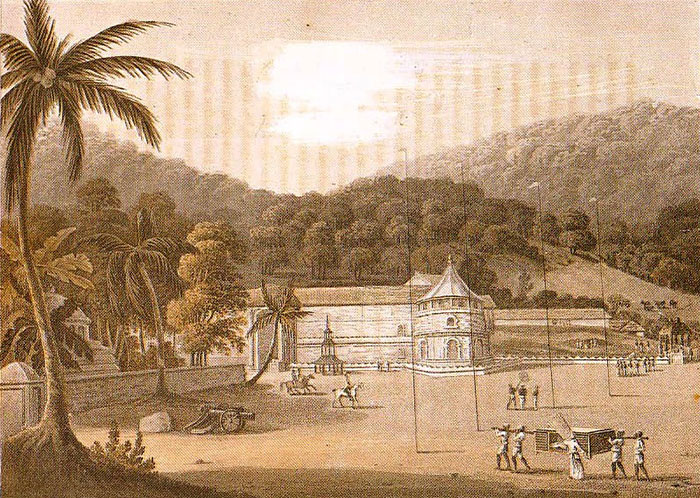

From John Davy’s An Account of the Interior of Ceylon

By Uditha Devapriya

Over the last two years I have been travelling to various parts of the country, trying to make sense of how rural communities operate, how they think and how they see the world. In all my travels I have come to realise how much rural beliefs and practices influence the most urban milieus in Sri Lanka. Dhanuka Bandara’s excellent essay on Gota Go Gama, published earlier this year, sheds light on this by charting the rural-utopian origins of the aragalaya, an ostensibly “urban” phenomenon. He ends his essay thus.

It is the essential anarchism of the “village” as a political category that fuelled the aragalaya and was able to bring together many competing factions to achieve a singular end that most people in Sri Lanka desired. Although the aragalaya ended anti-climactically, with Ranil Wickremesinghe coming to power and continuing the rule of the same old establishment, its real achievements should not be dismissed. Nor should anyone dismiss agrarian utopianism as a naive nationalist fantasy, as it could be the blueprint for a cosmopolitan future.

There is nothing naïve about nationalism, or about rural utopianism. This is particularly so because in Sri Lanka, the rural is present everywhere; it exerts itself over the urban in so many ways. I call this the ruralisation of the urban. Anthropologists and social scientists, for some reason, concern themselves with the obverse of this process, the urbanisation of the rural. Even Martin Wickramasinghe, who charted more presciently than did any other author the decay of the Sinhala village, focused on upheaval in the village and saw its decay as an axiom of the historical process, likening efforts to revive the past to a search for kalunika. In our focus on “changes in the village” – the gam-peraliya – we thus overlook what survives in the rural, and what gets transferred to the urban or suburban.

Those who had been to the aragalaya last year, for instance, would have noticed how quickly the rural elements swept over Gotagogama, how much their fears, anxieties, and frustrations dominated anti-regime discourses there. For these communities the aragalaya served a specific function, as an outlet to vent out their anger, not against an authoritarian quasi-dictator – Colombo society’s favourite depiction of Gotabaya Rajapaksa – but rather an incompetent administrator, a man who had failed to deliver.

There was a somewhat palpable though barely felt city-rural rift in the aragalaya. On his way to Gota Go Gama, a friend of mine shared a trishaw ride with a farmer who had travelled all the way from Nuwara-Eliya. What surprised my friend was that he had come to Colombo despite the fuel shortages, to express his anger against the government, a government he had voted for. “There is nothing more to hope or live for,” he had told my friend. “I want to be here, to join others let down by this man Gotabaya.” This had stymied my friend: “Until then I was unaware that such people existed.” I could not tell what surprised me more: the old man’s iron-clad determination to join the aragalaya, or the young aragalista’s ignorance, until then, of such communities and milieus.

The aragalaya brought these elements together, at least momentarily. The bourgeois elements did not mind being dominated by or dictated to by farmers and angry university students in a campaign they had patronised and sponsored. Yet what solidarity there was between these groups ended in a stalemate, if not anticlimax: the election of the Colombo upper classes’ favourite political figurehead as president. Should we frame this as a triumph of the urban over the rural, of urban “liberal” discourses of dissent over rural (though no means illiberal) discourses of rebellion? Such a reading would be simplistic, because it fails to account for the incredible diversity of the aragalaya. Yet it behoves us to reconsider and reframe the relationship between city and village in here.

We hold the most romantic and utopian notions of the village: our preferred prototypes are Anuradhapura and Kandy. As Bandara argues in his essay, such readings of the Sri Lankan – or Sinhala – village were reinforced by the most cosmopolitan people, including S. W. R. D. Bandaranaike. One notices in the writings of such people an urge to preserve the innocence of the village, to shield it from the corruption of the city.

In colonial Sri Lanka, the urge to preserve the village was expressed in different ways. Often it concealed insidious motives. In the late 19th century, Sinhalese elites and British officials alike deplored the tendency of villagers to educate their children in English. Oriental scholars like James de Alwis, educated in English schools but was taught Sinhalese and Pali by Buddhist monks, called for a shift to vernacular education. The comprador elite reiterated these calls; they probably resented their children sharing classrooms with village ilk.

What is so fascinating about this is that the colonial government had spent the better part of twenty or so years ceding education to Christian missions, weaning locals away from traditional “rural” customs and turning them into mock Englishmen. In doing so they overlooked the impact this would have on the rural-agrarian foundations of Sri Lankan society. In their rush to educate their children in English, the peasantry racked up debts which they later found they could not repay. Thus, from Colebrooke-Cameron’s emphasis on English education the government began opening Sinhala and Tamil schools. The class bias here was hard to miss: Sinhala and Tamil schools catered to the many, but were of an elementary nature, while the English schools, which catered to the few, were elite and superior.

Despite certain differences, the parallels between this and the aragalaya should be evident to all. In the aragalaya, too, the rural spread itself over the urban, to the extent of co-opting and dominating urban values, their worldview, their way of being. The homophobic insults I heard over the loudspeakers on July 12 were hardly to the liking of the Colombo liberal establishment, but they were eagerly consumed and reiterated by the protestors.

Yet the minute it reached saturation point, the urban elements opposed the domination of these elements and sought to reinforce their hegemony. As with English education in 19th century Ceylon, so with a mass uprising against an unpopular regime in the present century. In both cases, the bourgeoisie regained their hold, despite or more likely because of the penetration of rural elements in an eminently upper middle-class affair.

The difference between then and now is that while there were no safeguards against the hegemonical tendencies of the elite in the 19th century, there are now enough and more mechanisms to ensure a more equitable, representative social order.

What I mean here is that the right to vote and access to public facilities – in particular, free education – have liberated the rural underclass and middle-class and empowered it to take hold of the public imagination. The pushback against IMF reforms by these elements shows that despite the Colombo thinktankocracy’s missives about the necessity of such reforms, they will be resisted by those who suffer from them. Though Colombo society depicted the march to parliament on July 13 as a Leftist ploy, the prospect of such a putsch has a wide romantic appeal. Hence Anura Kumara Dissanayake’s recent intervention in The Hindu: what we need, he says, is not regime change, but national liberation.

The colonial State could prevent the permeation of the rural in the urban because it was in its interest and within its powers to do so. To allow such permeation would have diluted the hegemony of the elite, thus threatening the basis of colonial rule. The bourgeois State, by contrast, can stall this only at the risk of inciting insurrection or insurgency, as the Sri Lankan government found out at an exorbitant cost in 1988 and 2022.

It was the Gotabaya Rajapaksa regime’s disastrous fertiliser policies that alienated its single biggest electorate, the Sinhala peasantry. Though fuel shortages and power cuts affected the middle-classes, they devasted rural communities as well. These elements joined hands at the aragalaya, summoning the spectre of rural discontent. The bourgeois elements struck at them after a while, but their hold on the popular imagination has stayed.

In almost every way, then, the urban in Sri Lanka continues to be shaped – one could say determined – by the rural. Despite its best efforts, the colonial State could not prevent the penetration of the one into the other. The introduction of the vote, and of free education, has completed the circle. The changing village that Martin Wickramasinghe saw, and charted so impressively, is no longer restricted to the village: it is also in the city.

Free education, in particular, has opened a window to the rural middle-classes – the rural petty bourgeoisie – to enter the most elite enclaves and make their mark on institutions that were once zealously guarded by the English-speaking hoi-polloi. To paraphrase that student who debated the merits of secularism with me, these institutions are no longer the preserve of the elite, but of the best: the best in the country, emigres from the village. This is as true of Royal College, Peradeniya University, and Lake House – the triad of the Sri Lankan colonial elite, as Dayan Jayatilleka once observed – as it is of the aragalaya.

The writer is an international relations analyst, independent researcher, and freelance columnist who can be reached at udakdev1@gmail.com.