Sri Lanka & Sri Lanka

Wednesday, 3 January 2024 00:50 – – 30

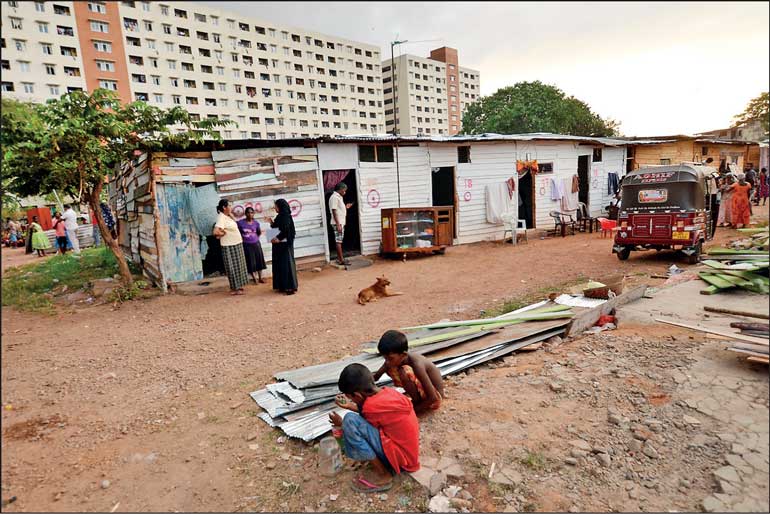

If the gap between the two Sri Lankas continues to widen, 2024 may become a year of conflagration – Pic by Shehan Gunasekara

“We talk about Tiananmen Square being all about democracy; it was because they had runaway inflation. The French Revolution wasn’t about liberté, fraternité, egalité, it was about rampant food price inflation”

– Albert Edwards (Societe Generale: Global Strategy Alternative View)

By Tisaranee Gunasekara

By Tisaranee Gunasekara

In China Mieville’s speculative murder mystery, The City & The City, two cities, Beszel and Ul Qoma, occupy the same territory. The citizens of each city are trained from infancy to unsee the other. They exist with each other all their lives without ever seeing, hearing, thinking about or consciously acknowledging each other.

Sri Lanka was always many Sri Lankas, divided vertically along ethno-religious and horizontally along class-caste lines. Perhaps our only moment of unity came as an unintended consequence of Gotabaya Rajapaksa’s economic insanity. Even the pandemic, a common danger, was experienced differently by Lankans (especially the urban poor and the Muslims). But in the fuel and gas queues of 2022, there was a rare sense of togetherness. From tenement gardens to luxury apartments, via middle-class houses, Gota go home rose as a single cry.

That conjunctural unity evaporated once Gota was made to go home. A speedy resolution of the Rajapaksa-wrought crisis was a common demand, but the recovery is being experienced differently by Lankans. This difference was manageable so long as policy makers tried not to burden, further, the already overburdened poor/vulnerable segments through indirect tax and rate hikes. Indeed, during the first post-Gotabaya year, commendable efforts were made to distribute the costs of economic recovery with some fairness. But this effort now lies largely abandoned. Ranil Wickremesinghe was more correct than his opponents when he opted for direct taxation to raise revenue; by returning to the seemingly easy path of hiking indirect taxes, he has regressed to the economic-policy-levels of those who seek to replace him.

2024, a crucial election year, dawned with a VAT hike. Prices of essential items, already too high for most Lankans, will increase even further, pushing more families below the poverty line. Even if the economy continues to grow in 2024, that growth will be of little or no benefit to a majority of Lankans who are struggling – and failing – to make ends meet.

One of the most distressing and devastating aspects of the new VAT hike is the removal of all books (locally published and imported, including educational books) from the exempted list. In consequence, the price of every book will increase at least by 18%, placing education beyond the means of more children from poor and low-income families. According to Samantha Indeevara, the head of Sri Lanka Book Publishers Association, policy makers, including the president and the treasury secretary, were informed of the disastrous consequences of this measure. The only official response was that the IMF made them do it.

Shortly before the 18% VAT on books went into effect, the Government decided to grant China’s Colombo Port Logistics Centre a generous 15-year tax exemption on income and dividends. This decision runs counter to the same IMF conditionality – ending all tax exemptions. The IMF and other multilateral agencies have been demanding the abolition of the Rajapaksa-era law which facilitates these direct tax exemptions, the Strategic Projects Development Act of 2008, in vain. The Wickremesinghe Government, contrary to its opponents’ sloganeering, is not a creature of the IMF. It merely uses the IMF to justify its decision to opt for the path of least politico-societal resistance. Reducing military expenditure, for instance, is hard, given the entrenched politico-ideological and socio-economic interests involved. It is much easier to increase VAT (including on books) and blame the IMF.

Gotabaya Rajapaksa’s direct tax cuts were hugely popular among the rich and the middle classes. When the Wickremesinghe administration corrected that ruinous error, political opposition, professional groups, Government sector trade unions, and some civil society organisations cried (mass) murder. Yet no such outcry was heard when the Government announced the VAT increase. Government teachers’ trade unions called a one-day strike to protest the re-imposition of PAYE even though no teacher earns enough to qualify for that tax. Yet those same unions seem unconcerned about the imposition of VAT on educational materials. The political opposition is yet to demand parliament debates on taxing books and the FUTA and the GMOA are yet to demonstrate against this anti-knowledge measure.

Gotabaya Rajapaksa’s direct tax cuts were hugely popular among the rich and the middle classes. When the Wickremesinghe administration corrected that ruinous error, political opposition, professional groups, Government sector trade unions, and some civil society organisations cried (mass) murder. Yet no such outcry was heard when the Government announced the VAT increase. Government teachers’ trade unions called a one-day strike to protest the re-imposition of PAYE even though no teacher earns enough to qualify for that tax. Yet those same unions seem unconcerned about the imposition of VAT on educational materials. The political opposition is yet to demand parliament debates on taxing books and the FUTA and the GMOA are yet to demonstrate against this anti-knowledge measure.

It is easy to tax books, food, or fuel because those hardest hit – the poor – do not protest as readily and as visibly as the middle classes. The real divide is not between the 1% and the 99% or even the 10% and the 90%. It is probably between 33% and 66%. A few months ago, Ranil Wickremesinghe had the political will to stand up to the richer one-third on behalf of the poorer two-thirds. Not anymore. The consequences of that abdication will be disastrous for him and deadly for Sri Lanka.

Greedflation

In late 2022 and early 2023, the price of eggs, probably the only affordable protein source for most Lankans, increased stratospherically. The Government asked for a reduction. Poultry producers refused, citing high costs. In January 2023, the Government imposed price controls. Producers responded by making eggs unavailable. Eggs became as scarce as milk powder once was.

The Government reacted by importing eggs from India, ignoring the cries of outrage from the poultry industry and political opposition. As the imported-eggs hit the market, prices decreased, making eggs affordable again to ordinary Lankans. Once the demand for exorbitant local eggs dropped, producers also had to allow their prices to reflect the new market reality.

That story is emblematic of one of the main issues assailing not just Sri Lanka, but most of the world: greedflation. Though the term is relatively new, the problem is not – an increase in inflation due to corporate/trader pursuit of über-profits. Once a fringe-left idea, it mainstreamed last year, as establishment economists tried to understand why food inflation – including in staples – remained high in the US and Europe, even when inflation was low; and why high food inflation was unresponsive to standard remedies like interest rate hikes.

In January 2023, the then US Federal Reserve vice chair, in a speech at the University of Chicago, pointed out that “retail mark-ups in a number of sectors have seen material increases in what could be described as a price-price spiral, whereby final prices have risen by more than the increase in input prices.” In March 2023, economists at the European Central Bank made the implicit explicit by stating that profit margins had become the main driver of inflation, responsible for 66% of real-terms price increases in 2022. The same month, Paul Donavan, chief economist of the UBS Global Wealth Management, warned of ‘profit-margin led inflation’ and European Central Bank executive board member Fabio Panetta expressed concerns about profits driving up inflation. In May 2023, Isabella Weber, an economist at the University of Massachusetts Amherst published a paper on the subject: Inflation, profit, and conflict: why can large firms hike prices in an emergency.

To explain how companies and other retailers get away with driving up prices via massive mark ups, a new term has been coined – excuse-inflation: the practice of blaming higher prices on extrinsic events, from weather and wars to pandemics and governments. According to Paul Donovan, profit-push inflation is sustained primarily by “the ability to sell this story that it’s not our fault we’re raising prices – the price of wheat’s gone up, so we’ve got to raise the price of bread” (New Statesman – 31.5.2023).

In Sri Lanka, profit-led inflation is a familiar phenomenon, the manipulation of rice prices by an oligopoly of large mill-owners being the best case in point. Price controls don’t answer, not in Sri Lanka; they merely cause shortages. Government interventions of innovative nature have better luck. In 2019, finance ministry under Mangala Samaraweera cooperated with small and medium scale rice millers to create a new rice brand called Shakti and release it to the market at an affordable price. This program was abandoned once the Rajapaksas returned to power. Rice prices sky-rocketed again. Newly-minted president Gotabaya Rajapaksa visited the Narahenpita Economic Centre, sat in a rice shop phoning officials, and eventually imposed price controls – to no avail.

In Sri Lanka, profit-led inflation is a familiar phenomenon, the manipulation of rice prices by an oligopoly of large mill-owners being the best case in point. Price controls don’t answer, not in Sri Lanka; they merely cause shortages. Government interventions of innovative nature have better luck. In 2019, finance ministry under Mangala Samaraweera cooperated with small and medium scale rice millers to create a new rice brand called Shakti and release it to the market at an affordable price. This program was abandoned once the Rajapaksas returned to power. Rice prices sky-rocketed again. Newly-minted president Gotabaya Rajapaksa visited the Narahenpita Economic Centre, sat in a rice shop phoning officials, and eventually imposed price controls – to no avail.

Political consequences of greedflation have been best analysed by economist Albert Edwards, head of global strategy at the 159-year-old French investment bank, Societe Generale. “Up until recently, policy makers, when they have commented in public about the need for restraint, have always focused on households demanding higher wages – warning that this would result in inflation becoming entrenched. These claims are ridiculous as households have suffered huge real wage cuts. It is companies that are driving inflation higher but this has been something Central Bankers are loath to mention” (Global Strategy Alternative View – 13.4.2023). The familiar trend of profit margins going down when costs go up has been replaced by one where profit margins increase when costs increase. ”The end of greedflation must surely come. Otherwise we may be looking at the end of capitalism. This is a big issue for policymakers that simply cannot be ignored any longer” (ibid).

To understand the outsized role played by greedflation in Lanka’s high living costs, it suffices to study the huge discounts offered by large and medium scale retailers periodically. The rate of discounts, which averages at about 20-30%, are indicative of the mark ups which determine ordinary prices. Unfortunately, Lankan politicians and policymakers seem uninterested in understanding this seminal issue. If the complex nature of inflation, its multiple roots and manifestations go unacknowledged, how can any Government face it successfully?

Taxflation

No taxation without representation was a key rallying cry of colonial America’s struggle for independence. In her biography of American founding father Samuel Adams, Stacey Schiff argues that the tax issue in colonial America was more a case of depiction than reality. The Stamp Act, which was so vilified that a servant in New England refused to enter a barn for fear that Stamp Act might be there, was never implemented. Tea tax benefitted American consumers since it actually lowered tea prices. Yet, politicians like Samuel Adams cleverly manipulated the issue, turning it into a political bombshell.

In Sri Lanka too, the tax issue is being manipulated to the benefit of the better off one-third and to the detriment of the rest. This is being done in two ways: concealing the difference between direct and indirect taxes; and being silent about the connection between defence expenditure/loss making state-owned enterprises and taxes.

Lankan politicians’ preference for the easy path of indirect taxes has turned taxflation into a major component of inflation. For instance, take fuel. Fuel price is determined not just by global prices (though that is the standard political line), but also by government taxes. Sometimes, the tax is even higher than the total cost of importing fuel – in end April 2020, the cost of importing 92 Octane litre was Rs. 28 while the tax was Rs. 108 (https://publicfinance.lk/ta/topics/The-Retail-Price-of-Petrol-and-Diesel-in-Sri-Lanka-is-Higher-Than-Their-Total-Costs-1624449192).

Since taxflation is caused by indirect taxes and not direct taxes, the obvious solution is to rectify the massive imbalance between direct and indirect taxes by shifting more of the burden onto direct taxes. Ranil Wickremesinghe’s proposal of imposing a wealth tax is an excellent idea; the problem is postponing its implementation until 2025, while hiking up VAT in 2024. Incidentally, the problem with the JVP in this area is not that it is socialist but that it is not socialist enough; in actuality, the JVP is more retrogressive than Ranil Wickremesinghe as it wants to cap PAYE top rate at 24%! A boon for high-earners. This is socialism not of Marx and Engles but of Putin and Xi, with happy queues thrown in.

Taxflation has been necessitated primarily by the ever increasing defence costs and the costs of maintaining such white elephant SOEs like SriLankan. The loss-making airline has just wet-leased two aircrafts from Belgium. The year before an incensed President Mahinda Rajapaksa took over SriLankan, it earned a post-tax profit of $ 7.8 million. In 2007, SriLankan gave to Sri Lanka; since ‘re-nationalisation’ Sri Lanka has been giving to SriLankan. And no politician, not even the ‘neo-liberal’ Ranil Wickremesinghe, is willing to bell such cats.

In Poverty, by America, Matthew Desmond explains society’s complicity in keeping people poor. “The American government gives most help to those who need it least. This is the true nature of our welfare state, and it has far-reaching implications, not only for our bank accounts and poverty levels, but also our psychology and civic spirit.” We are doing the same with every rupee we take from a poor family via indirect taxation to maintain the military and loss-making SOEs or to fund low taxes/tax breaks to the better off.

In Poverty, by America, Matthew Desmond explains society’s complicity in keeping people poor. “The American government gives most help to those who need it least. This is the true nature of our welfare state, and it has far-reaching implications, not only for our bank accounts and poverty levels, but also our psychology and civic spirit.” We are doing the same with every rupee we take from a poor family via indirect taxation to maintain the military and loss-making SOEs or to fund low taxes/tax breaks to the better off.

Professionals (especially doctors) who threaten to migrate if they are taxed, having reaped the full benefits of our free education system, are as complicit in keeping the poor in poverty as politicians. Monks like the chief incumbent of the Mihintale temple who rides a land cruiser V8 (the price of a second-hand vehicle of this variety seems to average at Rs. 50 million) and demand that people pay their electricity bills are as complicit in making non-poor poor as officials. The only difference is one of appearance; professionals who demand tax cuts and monks who demand free everything are better at hiding their avarice.

“The poor can see the affluent easily enough – on television, for example… But the affluent rarely see the poor,” wrote James Fallows in The blindness of the affluent. Unlike in China Mievelle’s cities, the habit of unseeing is one-sided. The upper one-third may not see the lower two-thirds, but the latter see the former, all the time. If the gap between the two Sri Lankas continues to widen, 2024 may become a year of conflagration, which will make the violence of 9-11 May 2022 seem like a picnic.