A jailed Imran Khan leaves Pakistan divided ahead of election

-

Published

In the Zeshaan household there is a ground rule – conversations about politics are not allowed when the family gets together.

It was a rule laid down shortly after Imran Khan was elected Pakistan’s prime minister in July 2018.

“I remember my father didn’t vote for Imran Khan in the 2018 elections. My sister and I didn’t talk to him for three months. We couldn’t sit together at meals or anything,” said Nida Zeshaan, who calls herself a “diehard Khan supporter”.

While political differences among families and friends are nothing unusual, no other politician has caused as many rifts in relationships in Pakistan as the former cricket star who rose to be PM before being ousted.

Khan was elected after he vowed to to fight corruption and fix the ailing economy, but he has been fighting a series of cases since he fell out of power in 2022. Several criminal convictions have now barred him from standing in general elections on Thursday. The 71-year-old claims these are politically motivated to boot him off the ballot.

And yet he still dominates conversation ahead of the 8 February vote.

‘We couldn’t sit together at meals’

“I can say it out loud that I love Imran Khan but my father thinks he is not a good politician,” Ms Zeshaan says.

The 32-year-old homemaker says she was especially drawn to the ideal of an Islamic welfare state (or Riyasat-e-Madin) championed by Khan “where equality and equity can be for everyone”.

But her father disapproves of the populist politician because of his perceived close ties to the military at the start of his political career.

The military is widely regarded as Pakistan’s most powerful institution and has deep influence on its politics. It has ruled the country directly for more than three decades since its formation in 1947, and has continued to play a big role thereafter.

No prime minister in Pakistan has ever finished a five-year term, but three out of four military dictators were able to rule for more than nine years each.

“I believe my father was judging Khan for his past life. Whatever it is, political differences are hard to resolve, so we’ve agreed not to discuss politics when we are together,” said Ms Zeshaan, who lives in Pakistan’s second largest city Lahore.

It is widely believed that Khan first rose to political prominence with support from Pakistan’s military establishment, but tensions between both sides emerged once he was in office. He allegedly fell out with then-military leaders over the appointment of the head of the country’s intelligence agency.

Then, four years into his premiership, Khan was ousted in a no-confidence vote that he alleges was backed by the US in a “foreign conspiracy” that also involved Pakistan’s military. Both the US and the military have rubbished these allegations.

This galvanised his supporters, who like Ms Zeshaan, have jumped to his defence.

“Unfortunately he did not get enough time and chances to implement all of these things. Also, the circumstances and other powers of the country didn’t let him perform,” she said.

Many Pakistanis are frustrated that his economic and anti-corruption pledges have rung hollow, but his popularity has not waned even from behind bars.

A Gallup opinion poll in December showed his approval ratings stand at 57%, putting him narrowly ahead of rival Nawaz Sharif with 52% of the votes. A Bloomberg survey last month showed Khan to be the top pick among some Pakistani finance professionals to run the country’s failing economy.

Some citizens say Khan sparked a political awakening by portraying himself as a “change candidate” who promised to end dynastic politics.

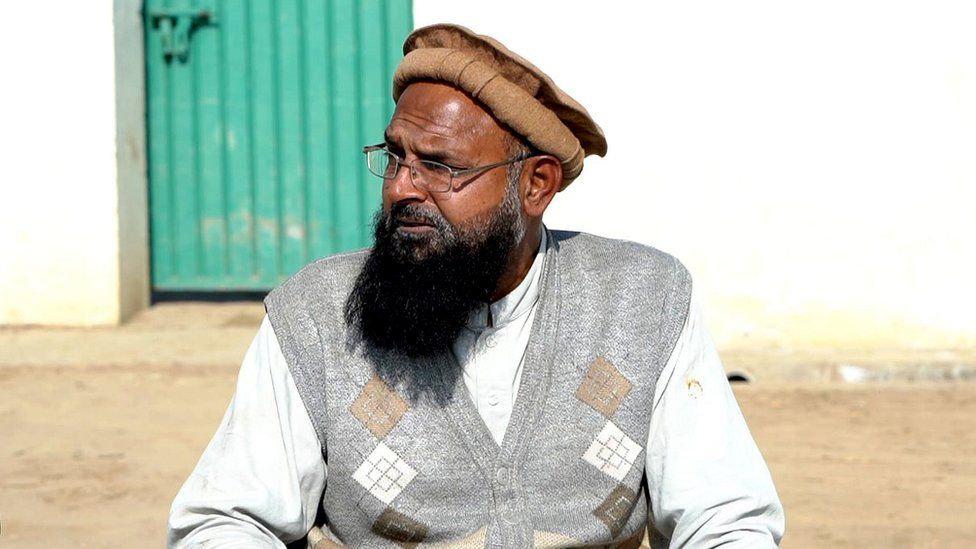

“It was Imran Khan and his party who explained to a villager like me how two parties plundered the wealth of the nation. He taught us how to vote for change,” said farmer Muhammad Hafeez, who lives in Nabipura, a village in Punjab.

Mr Hafeez was referring to the Pakistan Muslim League (PML-N) and Pakistan People’s Party (PPP) – led by two political families that have dominated Pakistani politics for decades.

Once bitter rivals, they united to topple Khan and his PTI in 2022.

The PML-N candidate, Nawaz Sharif is widely expected to win the election and become prime minister for a record fourth term.

This is being seen as a dramatic turnaround in his political fortunes. He was ousted from his second term in a 1999 military coup and sentenced to life imprisonment on charges of hijacking and terrorism, and also convicted of corruption.

He returned to Pakistan from exile in Saudi Arabia in 2007, and was elected prime minister for a third time in 2013. He was removed from power in 2017 following a corruption investigation related to the Panama Papers, and was sentenced to seven years’ jail in a separate graft case a year later. This paved the way for Khan to become prime minister.

Now it is Khan who is behind bars and the path for Sharif to become PM is clear. Many believe that he is the military’s preferred candidate this time around.

“Khan created awareness. Previously, people were not politically aware enough to speak up for their rights,” Mr Hafeez said.

But other observers allege that Khan’s politics are nothing more than rabble-rousing and populism.

“We are supposedly expected to believe this was a wronged man, almost a martyr, who ostensibly had a clean record prior to entering this murky fray,” said Burzine Waghmar from the University of London’s SOAS South Asia Institute.

“[But] Khan’s style of governance comprised avoidable squabbles with the military top brass and irresponsible demagoguery.”

‘Divided loyalties’

Some believe Khan’s biggest offence was challenging the military, which has long been the ultimate arbiter of politics in the country – and is widely referred to as the “establishment”.

Other former prime ministers have fallen out with the army in the past but few have come as close to Khan in dividing loyalties there.

Some retired military officers – typically expected to toe the line – have spoken against the army’s political interference.

They allege that this has sparked a crackdown by military leaders against them. One retired senior officer said he was instructed to “stop talking in favour of Imran Khan”.

“I said I am not speaking in favour of him, nor am I speaking against the military. I am against the policies and interventions of a few individuals who are causing harm to the country,” he claims.

Some retired military officers told the BBC they were implicated after Khan fell out of power for not supporting the no-confidence vote against him. Others claim they had their pensions and government benefits suspended, while others received threats that further action could be taken against them.

Many have since gone quiet.

The BBC reached out to the military regarding these allegations but did not receive a response. A spokesman of the military said last year that retired army officers are “assets of the army but they are not above the law”, warning also that they should not get involved in organisations that “wear the garb of politics”.

But with Khan now out of the running and the PTI too dealt a big blow after Pakistan’s election commission banned its iconic cricket bat symbol from ballot papers in January, it may look like Khan has been effectively neutralised.

But instead, political divisions across the country look set to deepen.

Back in Lahore, Imran Khan supporter Ms Zeshaan said: “Even my friends know my political lines. Whenever any of them tries to cross them I stop meeting them or we usually end up fighting with each other.”

Additional reporting by Nicholas Yong in Singapore