Devolution and Comrade Anura

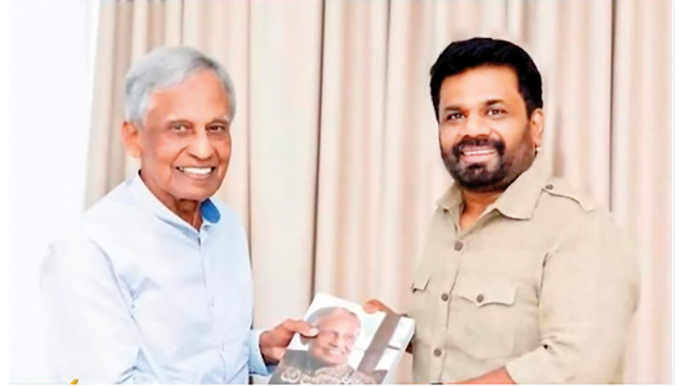

The writer (L) presenting his memoirs to Dissanayake. (A file photo)

By Austin Fernando

(Former Secretary to the President)

About ten months ago, among other things, I informally discussed the devolution of power with Anura Kumara Dissanayake, who was an MP at the time. The consequences of his low-priority approach to devolution, as predicted then, were reflected in the presidential election results in the North and the East. Perhaps, there were other reasons also for the low level of popular support for him over there. Now that he is the President of 23 million Sri Lankans, he must consider the presidential election results in the North and the East as a guide. Probably, the Indian External Affairs Minister Subrahmanyam Jaishankar has already reminded him of that.

Sri Lankan politicians’ mood changes

The policies of Sri Lankan politicians on power sharing are characterized by inconsistencies. Former Ministers Basil Rajapaksa and Prof. G.L. Peiris promised Indians the implementation of the 13th Amendment (13A). Though Namal Rajapaksa has specifically rejected the devolution of Land and Police powers, President Mahinda Rajapaksa promised “13A+,” including those. In Delhi, President Gotabaya Rajapaksa said 13A could not be implemented “against the wishes and feelings of the majority (Sinhala) community.” But he had solemnly declared that he would uphold and defend the Constitution, of which 13A is an integral part! The Indian political leaders’ policy on the devolution here has remained consistent.

We have conveniently forgotten that during the Oslo Peace Talks on 05 December 2002, the Sri Lankan delegation led by G. L. Peiris and the LTTE delegation led by Anton Balasingham agreed to “explore a solution founded on the principle of internal self-determination in areas of historical habitation of the Tamil-speaking peoples, based on a federal structure, within a united Sri Lanka.”

“Federal,” “areas of historical habitation,” and “internal self-determination” are anathema to many Southern politicians and not understood by civilians. Today, Ranil Wickremesinghe and Pieris will certainly dissociate themselves from the Oslo Declaration.

Wickremesinghe, who supported the passage of 13A and appurtenant legislations, was Prime.

Minister (PM) when the Oslo Declaration was made. But now he is unwilling to devolve police powers to Provincial Councils (PCs). Gotabhaya Rajapaksa informed Indians that he must “look at weaknesses and strengths of 13A.” Had he said so as an inexperienced President in 2019, it would have been tolerable, but he said so after 22 months in office. It reflected a lack of knowledge of governance systems on his part or something up his sleeve.

Evolution of 13A

In this background, it is appropriate, to reflect the evolution of 13A to evaluate it as against what was demanded in the name of devolution.

Sri Lanka came under pressure to devolve power following Black July (1983) and the beginning of the armed conflict. The contention that the Indians wished for Sri Lanka’s division through devolution is not true. India has always respected our sovereignty and territorial integrity owing to its experience with conflicts in Mizoram, Nagaland, etc.

On 01 March 1985, President J. R. Jayewardene personally sought Indian Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi’s intervention to prevent the movement of armed terrorists from India and Sri Lankans seeking refuge in India. On 01 December 1985, the Tamil United Liberation Front (TULF) presented its proposals for devolution to Gandhi in a bid to pressure Sri Lanka to agree to power-sharing.

The salient features of the proposal were as follows:

• Sri Lanka—”Ilankai” be a union of states,

• Amalgamated Northern and Eastern Provinces, a ‘Tamil Linguistic State’, which cannot be altered without their consent,

• Parliament reflecting ethnic proportion shall be empowered to make laws under “List 1″ for Defense, Foreign Affairs, Currency, Posts / Telecommunications, Immigration/Emigration, Foreign trade/Commerce, Railways, Airports /Aviation, Broadcasting/Television, Customs, Elections, and Census only, • List 2” had all other subjects, inclusive of Law and Order, Land, etc., with the State Assembly possessing law-making powers, • Any person resident in Sri Lanka, on 1st November 1981, who is not a foreigner shall be a Sri ankan citizen, • No Resolution or Bill affecting any “nationality” should be passed by Parliament without the agreement of that “nationality,” (The term ‘nationality’ is misleading.)

• The State Assembly to be empowered to levy taxes, cess/fees, and mobilize loans/grants,

• Special provisions for Indian Tamils,

• The elected members are to be given enhanced powers, • Upgrading the judicial system, e.g. Provincial High Court to Appeal Court, and, • Muslim rights to be cared for.

The Jayewardene Government rejected the proposal out of hand. The TULF again addressed Gandhi (17-1-1986), incorporating more sensitive issues such as ‘traditional homelands,’ demographic imbalance, etc. Jayewardene steadfastly advocated a military solution and the war was dubbed as “genocide” by former Indian Minister B.R. Bhagat and several Lok Sabha members. The latter demanded punitive interventions such as ‘crushing Sri Lanka in 24 hours” (Sri Kolandaivelu on 29-4-1985), and Sri Gopalaswamy on 13-5-1985, asking India “to undertake every possible means, including military interventions.”

Gandhi would have been satisfied with the Sri Lankan proposals of 09 July 1986, prepared after consulting Minister P. Chidambaram, which fitted the Sri Lankan constitutional basics. There were ‘Notes’ incorporated into the proposals on PCs, law and order, and land settlements inclusive of land alienation under the Mahaweli Project, with allottees identified based on ethnicity. On 30 Sept.,

1986, the TULF responded to India in detail to the government’s proposals, adding more propositions.

Gandhi was mindful of Lok Sabha’s demands. He vented frustration in Lok Sabha and abroad (e.g. Harare). Efforts to project him and India as weak exasperated him and drove him to get tough. On 02 June 1987, he threatened to send a flotilla with ‘humanitarian assistance’, and on 04 June 1987, Indian Aircraft violated Sri Lanka’s airspace and carried out aid drops in the North. No superpower stood with us on this blatant violation. No wonder Jayewardene agreed to sign an Accord and follow up by introducing 13A.

After the signing of the Accord, the Indian Peace Keeping Forces (IPKF) were deployed in Sri Lanka.

Lt. General A. S. Kalkat, in an interview with Nithin Ghokle, has admitted that the deployment of the Indian army here was a mistake. Jaishankar (one-time political adviser to the IPKF- 1988-1990), has said in his ‘The India Way,’ that it was a ‘misadventure.’ We are aware of the IPKF’s ‘mistakes’ and ‘misadventures’ like the Valvettithurai Massacre of 64 persons on 02 August 1989, and more, best known to Kalkat and Jaishankar. Importantly, the IPKF operations instilled fear, especially conditioning Tamil people’s minds to search for whatever possible solution.

Concurrently, as explained by then-Indian Foreign Secretary A. P. Venkateswaran, Jayewardene met Gandhi in mid-November 1986 in Bangalore, along with Ministers Natwar Singh, Chidambaram, and himself, and Jayewardene allegedly ‘pleaded’ with Gandhi to send the Indian Army to prevent his government from collapsing, due to the JVP attacks in the South, and LTTE in the North. It was his sheer desperation that drove Jayewardene to opt for the Accord and 13A. After this meeting, Gandhi sent Chidambaram and Natwar Singh to Colombo knowing our vulnerability.

On 19 December 1986, they submitted the “emerged” proposals. The salient points were as follows:

* The Eastern Province to be demarcated minus Sinhala majority Ampara Electorate.

* A PC was to be established for the new Eastern Province.

* Earlier discussed institutional linkages to be refined for Northern and Eastern PCs. The

intention would have been to merge later under a second-stage constitutional development.

* Sri Lanka was willing to create a Vice Presidency for a specified term.

* The five Muslim parliamentarians from the Eastern Province may be invited to India to discuss matters of mutual concern.

The foregoing demands show how India tried to match the Tamils’ interest, vis-a-vis the wishes of the majority community.

Military operations continued provoking India, which threatened to abandon its intervenor role on 09 February 1987, unless Colombo pursued a political solution. Jayewardene responded on 12 February 1987, insinuating calming down on military actions, promoting negotiation and administration, and paving the release of persons in custody. This was how India reacted when rubbed wrongly.

Under successive governments, PCs were weakened by the withdrawal of powers and lacked cooperation. This may have led Jaishankar to address President Dissanayake, whose party is considered averse to 13A. This is the perception of the Tamil MPs, who have recently sought US Ambassador Julie Chung’s intervention for correction. Such aversion to PCs is hard to overcome as evident from an NPP’s public statement that devolution will not include Land and Police powers. It said so close on the heels of Jaishankar’s request that 13A be fully implemented.

Flashback to 1986

The Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) stalwart, Jaswant Singh posed seven questions in Lok Sabha on 13 May 1986, based on the situation in Sri Lanka. They are relevant even today.

* What is the Indian stand in the debate on devolution and delegation?

* Where do India and Sri Lanka stand on the Northern and Eastern Provinces merger?

* What is the stand on land use by the Indian Government, the Government of Sri Lanka, and

the Tamil groups?

* What is the status of the language?

* What is the stand on Law and Order?

* What is the time frame for reaching a solution?

* What is the Indian Government’s stand on the foreign threats emerging in the context of the Sri Lankan issues?

If Jaswant Singh were alive today, he would either join the critical Lok Sabha Members or question PM Modi and Jaishankar why the Accord has not been implemented. Jaishankar’s reminder to President Dissanayake would have been due to his frustration stemming from:

* 13A being “paralyzed” by partial implementation, and delayed elections.

* The demerger of the North and the East legally

* The delay in devolving land and police powers

* The language issue has not been fully resolved despite constitutional guarantees

* Absence of a timeframe for a solution, even after crushing the Tigers in 2009, and,

* Increasing threat to India, especially from China.

Parallelly, the field situations have changed. Military operations have ceased. Public attention has been shifted from conflict to human rights and humanitarian concerns, returning refugees, and reconciliation. 13A has been internationalized owing to the incorporation thereof into UNHRC Resolutions by Mahinda Rajapaksa and Wickremesinghe in 2009 and 2015 respectively. Intense lobbying by Diaspora groups has also contributed to this situation. These are daunting challenges before President Dissanayake. 13A is only one of them.

What is in store?

As seen above, the 13A has trudged a rough path to be accepted domestically or in India. Parliamentarians resigned, opposition politicians and Bhikkus protested on roads against it and violence was experienced. If the rejected proposals had been accepted the consequences would have been disastrous. However, devolution has come to stay and is viewed as a ‘Made-in-India’ solution.

President Dissanayake must be prepared for negotiations with relevant parties on devolution and hence needs to study India’s experience with devolution. For instance, on the devolution of land powers, Dissanayake can refer to how the Indian government changed Jammu Kashmir rules allowing the center to release lands to Indians to attract development/investment. They permitted even non-residents to own immovable property in Jammu and Kashmir and transfer agricultural land for non-agricultural purposes. India considered changes as her “internal affairs”, which may not be acceptable to them if we say so on 13A!

PM Modi has declared that such abrogation brought about security, dignity, and opportunity for all communities that had been deprived of development, and helped eliminate corruption. If he wishes, President Dissanayake can make similar reasoning to bolster his arguments concerning devolution.

Indians also have asymmetrical administration in the Himachal and Uttarakhand States but do not apply that to Jammu-Kashmir, which we also could duplicate. However, asymmetrical devolution is extremely complex and warrants serious legal attention.

It is now up to President Dissanayake’s legal and administrative experts to propose how to

incorporate propositions concerning devolution into the proposed new Constitution. India might compromise on devolution and concentrate more on economic and humanitarian rights interventions. Such attitudinal change is the need of the hour.

Indian National Security Advisor Ajit Doval, a respected negotiator/strategist, recognised even by Chinese President Xi Jinping in Kazan, has advised Tamil politicians to negotiate with a winnable candidate and secure Tamil aspirations through negotiations. His wise counsel was not heeded by some Tamil politicians, who, while rejecting 13A, demanded a federal system with self-determination powers for Tamils, which is a non-starter. By reminding President Dissanayake of the need to implement 13A after Doval’s visit, New Delhi sent a clear message concerning Sri Lanka: that it does not consider self-determination or a federal system as a solution.

Hence, Tamil politicians also must revise their approach in light of the aforesaid message. Based on Jaswant Singh’s queries and current political trends, if Tamil groups reject 13A, a new power-sharing mechanism sans federalism must be proposed. Perhaps, the new Constitution promised by Dissanayake may offer an alternative to bring about nation-building, with equality, dignity, justice, self-respect, and inclusivity, through a political process. They are the crux of Tamil demands.

Some believe that devolution can be achieved through Local Government Authorities in contravention of international norms of devolution and the Principle of Subsidiarity. Additionally, making all political parties think out of the box is a formidable challenge. Yet, consensual decision-making is needed to ensure the sustainability of any mechanism.

Meera Srinivasan of The Hindu has said:

“Despite India’s known support to the Mahinda Rajapaksa administration in defeating the LTTE in 2009, sections among the Sri Lankan southern population remain India-sceptics, wary of the big neighbour, who ‘interfered’ in Sri Lanka’s ethnic conflict, ‘sided with Tamils’. They resist India’s commenting on power devolution or conduct of elections to PCs and oppose any Indian role in developing national assets.”

India and the Tamil political establishment may adapt to this Sinhala mindset. The upcoming parliamentary election is expected to enable the NPP to form a government. If so, it will be timely to change narratives, without risking the redirection of the government’s political allegiances elsewhere. India should be cautious. Change should be achieved through wider consultations and agreements.

From Bhandari to Vikram Mistri, and Rajeev Gandhi to Narendra Modi, Indians also have acted like their Sri Lankan counterparts in managing the national question here, as evident from Sri Lanka’s failure to implement the 13A fully for 37 years, and India’s failure to convince Sri Lanka of the need to use 13A to solve the national question.

Today India has to deal with a Sri Lankan leader, who is different from predecessors. It is hoped that Jaishankar and others will be able to persuade him to get to the genuine track to explore a solution for the national question. Good luck to Ministers Subrahmanyam Jaishankar and Vijitha Herath, Secretaries Vikram Mistri and Aruni Wijewardane, and High Commissioners Santhosh Jha and Kshenuka Senevirathe!