Features

How DS Senanayake handled a ‘leak’ relating to Tarzie Vittachi

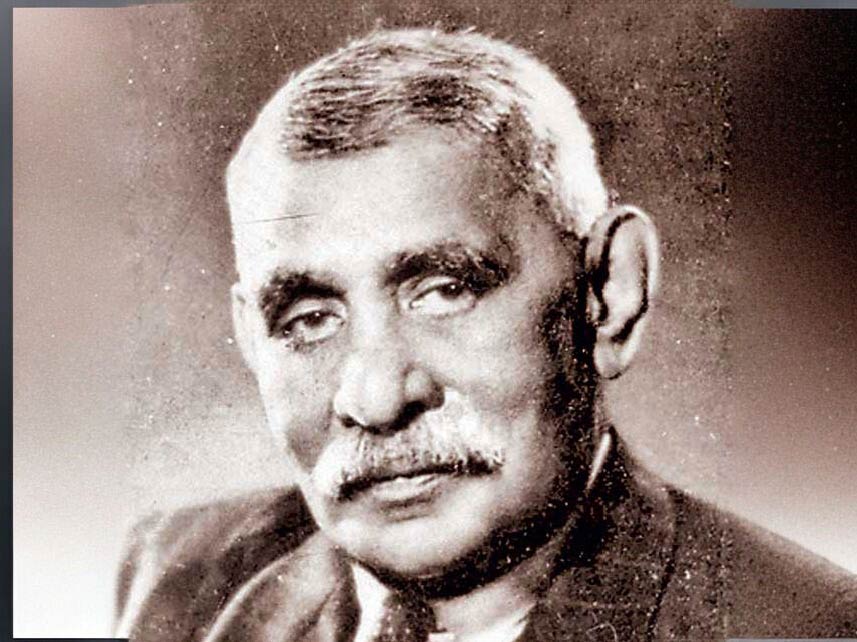

DS Senanayake

“An Instructive Example of Moderation and Transparency”

(Excerpted from Chaos and Pattern volume 11 of autobiography of Godfrey Gunatilleke)

Towards the end of 1951, there were signs that the government was preparing for the elections due to be held in 1952. I learnt of some of the preparations that were being made in a conversation with Athukorale (official Secretary to the PM). I had seen Esmond Wickremesinghe visiting the prime minister on several occasions.

Athukorale casually indicated to me that Esmond Wickremesinghe was consulting the prime minister on the approach that should be taken by the Lake House press in the forthcoming elections. It was well known that the Wijewardene brothers, D. R. and D. C., the proprietors of Lake House Press, were close friends of Senanayake and strong supporters of the UNP. Esmond Wickremesinghe was the son-in-law of D. R. Wijewardene and managing director (editorial) of Lake House.

In passing, Athukorale also mentioned that Esmond Wickremesinghe was proposing to post Tarzie Vittachi to the Lake House office in the UK during this period, as he may try to pursue his own independent line, and that his trenchant “no holds barred” criticism of all and sundry may run counter to the approach that the management of Lake House would like to take.

The Lake House, both English and Sinhala, was the dominant voice among the media and appeared to wield enormous influence over public opinion however, this view was proven to be totally mistaken by the results of the 1956 election.

A day or two after my conversation with Athukorale, Jeanne Pinto, who had been one of my fellow students in the English Department and who had joined the staff of The Observer, happened to visit me in my office. Bella (the writer’s wife) and I were close friends of Jeanne. In the course of our conversation, she complained that her relationship with Tarzie, under whom she worked, was very disagreeable, that she was unhappy in her work, and that she was in half a mind to leave Lake House.

I gathered that she found Tarzie’s remarks and his male chauvinist humour difficult to tolerate. I then mentioned that I learnt that he was going to UK to be in charge of the Lake House office there. Jeanne was overjoyed hearing this news. In her next meeting with Tarzie in his office, she asked when he would be leaving for the UK, with a taunting edge to her voice.

The news took Tarzie by surprise, and he made inquiries from Wickremesinghe, who in turn had been furious that the information had leaked. He stormed into Athukorale’s office, as only Athukorale had been privy to his discussions with the PM. Athukorale realized at once that it was only Godfrey Gunatilleke who could be responsible for the leakage. He sent for me and asked me what happened. My first reaction was one of puzzlement, as I had not thought that the information was confidential, and that Tarzie had already been informed about the transfer.

I was not aware of the need to keep it confidential and quite ignorant of any political ramifications it may have had. Athukorale accepted my explanation without any reservations. But he said that Esmond Wickremesinghe had already spoken to the PM about the leak and that he would arrange for me to meet the PM personally and give the full account of what had happened, as I had given it to him.

Early one morning thereafter, I met the prime minister at Temple Trees. He was in a relaxed, genial mood and greeted me with a smile. He asked me to sit down and looked at me inquiringly. I said I had come in connection with the leakage of information regarding Tarzie Vittachi’s transfer and proceeded to give him a full and exact account of what had happened. My narration would have taken about four to five minutes at least, but he listened to me patiently without interruption, with a look that had a shade of amusement.

He said, “Well, you see the information should have been kept confidential, as Esmond had planned to speak to Vittachi later, after he had made the necessary arrangements. Anyway, young man,” he went on to say, “you must always be careful with journalists.” There was no tone of reproof or annoyance in his voice, and he seemed to be quite satisfied that mine was a complete truthful narration of what had happened. From his manner, I saw that he had no desire to “cross-examine” me on the explanation given, and seemed to accept my plea that I had no knowledge that I was expected to keep the information confidential.

A tray with cakes and a pot of tea, along with sugar and milk in separate bowls, had been brought in and placed on a table close to where I sat, and the prime minister invited me to serve myself. He leaned back in his chair and inquired how I had come to know Jeanne Pinto. After I replied, he said, “I think I can now identify your young friend. She is the young woman who is ‘carrying on’ with Sardha Ratnaweera.”

Sardha Ratnaweera was a wealthy proprietor of a jewellery firm. I knew that Ratnaweera was married and had a family with children. I was quite taken aback at the news; it appeared to be totally uncharacteristic of the Jeanne Bella and I knew, and I thought that if Jeanne was involved with Sardha, we would have heard of it.

My first impulse therefore was to speak chivalrously “in defence” of Jeanne and state firmly that the information the PM had could not be correct. I thought I would have been unfair to Jeanne if I did not speak up for her. I was guided by values I had imbibed that required that you should not remain silent if someone speaks ill of your friend in your presence. But I held back, as it seemed inappropriate for me to do so. I merely expressed surprise and said I had no knowledge of it. His tone suggested that he was cautioning me about my friends.

Later, I found the prime minister’s information was correct. A few months later, Sardha Ratnaweera divorced his wife and married Jeanne. After a short time, however, their marriage broke up as well and ended in divorce.

When the meeting was over, I felt grateful to the prime minister for the way he dealt with the problem. He treated the whole affair as a storm in a teacup and showed a sense of proportion that came naturally to him. The transparency with which both the prime minister and his secretary handled the matter became for me an example that I should emulate.

Things might have been -different

if Athukorale had not approached the incident with an open mind and believed that my lapse was wholly unintentional. From thereon, there were no hidden doubts and misgivings and everything concerning the incident could be disclosed and discussed openly.

(The writer is the last surviving senior public servant who worked with Prime Minister DS Senanayake)