Features

IN RETROSPECT

by Dr Nihal Jayawickrama

I had always thought that autobiographies were written after retirement. I hope this request from the LAW MEDIA for the story of my life, or more particularly, my experiences before Hong Kong, is not a gentle reminder that my time is up. I prefer to think that you simply wish to get to know better the only South Asian on the Faculty or are curious to know why a lawyer wants to teach law rather than practise it.

One of the earliest decisions I made in my life was to be a lawyer. I was not yet nine. All my older relatives, including my father, were lawyers, and it did not seem as if I had any choice in the matter. Where I did have a choice was regarding what I would do after becoming a lawyer. I would never be a law teacher or a civil servant; I only wanted to be a practitioner. But “God moves in a mysterious way, his wonders to perform”, and life did not quite turn out the way that I had intended it to be.

I read law for three years at the University of Ceylon, on a picturesque, residential campus, nestling among the tea plantations, high in the mountains of central Sri Lanka. Sir Ivor Jennings, vice-chancellor, had, on 3,500 acres of lush tropical vegetation, created for the Arts and Law Faculties a veritable ivory tower, away from all the mundane activities of city life.

Through it flowed the Mahaweli, Sri Lanka’s longest river, whose secluded sandy banks offered a welcome retreat from contracts, torts and trusts. It was there that I “proposed” to my future wife, with dire consequences. Her parents, to whom she dutifully communicated this fact, promptly removed her from the campus. They were not impressed by a potentially briefless barrister. A negotiated settlement, with severe restraints upon my movements, enabled her to resume her academic career.

With Shirle Amarasinghe, Permanent Representative and Deputy Perm Rep. Yogasunderam at UN General Assembly in 1972

A further year of study at the Ceylon Law College, and six months apprenticeship, and I was a fully qualified Advocate (as barristers are referred to in Sri Lanka). I wanted to take my oaths before my uncle, a Judge of the Supreme Court, who had brought me up after my father’s death when I was quite young. He was then presiding over a controversial criminal trial which later found its way into the law reports as The Queen v. Liyanage (1965) 1 All ER 42. He took the unusual step of sitting in another court for five minutes for the purpose of admitting me to the Bar. Ten days later, the Liyanage Bench dissolved itself, holding that it had no jurisdiction to sit as the Supreme Court since it had been nominated to do so by the Minister of Justice. I often wondered what my position would have been had I been admitted by that “court”.

I spent eight very happy years at the Bar. I learnt my way around as a junior in the chambers of several successful lawyers, each specializing in different areas: original court work, criminal appeals, tax law, industrial law, and judicial review. At the end of the third year, I felt confident enough to step out on my own; to decline appointment as a Crown Counsel; and to get married.

The next five years were spent almost entirely in the appeal courts where, much to my satisfaction, I found myself appearing in court daily. A short break enabled me, on a UNESCO Fellowship, to spend a few months as a member of the legal staff of the International Commission of Jurists in Geneva. There, under a remarkable man, Sean MacBride, then Secretary-General and later a Nobel peace prize winner, I was initiated into the world of human rights law. Back in Ceylon, I found myself becoming increasingly involved in legal work on behalf of the Sri Lanka Freedom Party, which was then in Opposition (and consequently, in several political trials), and in the activities of the Bar Council to which I had been elected as representative of the junior bar and then as its secretary.

At the 1970 general election, I represented Mrs. Bandaranaike, the SLFP leader, as her counting agent. When, in the early hours of the morning, I reported back to her that she had won her seat by a comfortable majority, the other results made it clear that she would be the country’s next Prime Minister. Forty eight hours later, she invited me to accept office as Permanent Secretary to the Ministry of Justice, a position hitherto held by senior judges. It was a difficult decision to make. It meant abandoning the Bar where I was not only very happy, but also well settled. Finally, with an assurance from the Prime Minister that what she expected of me was a programme of radical law reform, and that I would have a completely free hand, I accepted the challenge.

The Secretary for Justice was the head of the Ministry of Justice, the Minister being a member of parliament and not necessarily a lawyer. The departments under the Ministry, which the Secretary was required to supervise, included those of the Attorney General, Legal Draftsman, Public Trustee, Government Analyst, Bribery Commissioner, Commissioner of Prisons, the Law Commission, the Courts and the Conciliation Boards. The heads of these departments, as well as my assistant secretaries, were all much older than I, and were all males. The latter deficiency was soon rectified by the appointment of a woman barrister as the secretary of the Law Commission. Once more, the unexpected happened. Following the sudden death of the Attorney General, I was required to leave my one-week-old job and move to another. On my 33rd birthday, I took my oath of office as Attorney General.

I spent seven eventful, exciting, tension-filled years in the Ministry of Justice. In a sense, they were years of achievement: the drafting of a new constitution that brought into being the Republic of Sri Lanka; the abolition of the right of appeal to the Privy Council and the establishment in Sri Lanka of a Court of Final Appeal; a new courts structure, including a Constitutional Court for the reviewing of bills; new criminal, civil and appellate procedure laws; the transition from English to Sinhala and Tamil also as the languages of the original courts; the fusion of the two branches of the legal profession; and the expansion of the concept of conciliation.

In another sense, they were also years of recrimination: a highly publicized encounter with the Supreme Court which culminated in my being ordered by the Chief Justice to leave the Bar Table at a ceremonial sitting of the court; a prolonged conflict with the Bar which could not understand why one of its “own” would want to change so radically the life-style of the profession, and even threaten to introduce “barefoot lawyers”, and suggest the control of fees; and an insurrection that filled the prisons (and two universities which were converted into prisons) with 18,000 idealistic young men and women who believed that they could take control of the government by the simple device of attacking all the police stations in the country in one night.

This latter enterprise resulted in my being designated under the Public Security Ordinance as “competent authority” for the release of detainees – an exercise that was extended over four years, much to the indignation of Amnesty International, the International Commission of Jurists and other human rights activist groups in many of which I was a member.

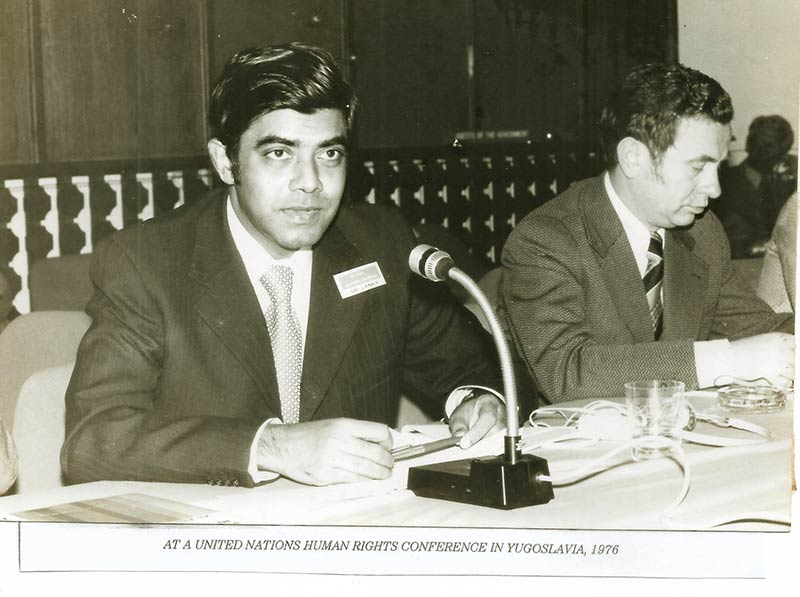

While functioning as Justice Secretary, I was also called upon to represent my country at the United Nations and in regional and international organizations, notably, the Asian-African Legal Consultative Committee, and the UN Congress on Crime. The UN was once described by U Thant as “an institution which enables a government of a member state to carry on a simultaneous conversation with the rest of the world”. Its General Assembly sessions always provided a touch of drama.

There were showers of chrysanthemums from the public balconies when Salvador Allende arrived to make a memorable speech in which he almost predicted his impending untimely death. In contrast, screaming demonstrators jammed the streets of New York to protest against the invitation extended by the UN to PLO leader Yasser Arafat. At the UN my work was principally concerned with human rights, and I recall the occasion when we began drafting a convention on torture, several years before it was to reach fruition. While on a visit to the US Supreme Court, during a break from the UN, I had the privilege of being invited to tea by that legendary libertarian activist, Mr. Justice William O. Douglas, then well into his seventies, but who had only recently married his young vivacious law clerk.

At a conference held in Colombo of Non-Aligned States, I was serving in the chairperson’s secretariat. It was an exciting week when out of the cover pages of TIME and NEWSWEEK there stepped out into real life exotic figures like Gaddafi of Libya, Sadat of Egypt, Assad of Syria, Makkarios of Cyprus, and Tito of Yugoslavia. My last assignment for the government was to have been as Ambassador to the Soviet Union; an assignment that I accepted and then declined for purely personal reasons: my daughter was barely two years old, and my wife was not willing to expose her to the sub-zero Moscow winter at that age.

Following the defeat of the Bandaranaike government at the 1977 general election, I resigned from my office in the hope of resuming my legal practice. The Bar, however, was unforgiving, and the new government was exceptionally vindictive. Therefore, in 1978, I accepted an offer from King’s College London of appointment as a Research Fellow for the purpose of researching the emerging international human rights law under Professor James Fawcett, then President of the European Commission of Human Rights. After three months in London, I returned home on a brief visit, only to find my passport being impounded on arrival. During the next one year. I was subjected to an inquiry by a special presidential commission on charges of “misuse and/or abuse of power” while serving the previous government, some of the charges being based on matters as hilarious as the Supreme Court “incident” and the proposal to introduce “barefoot lawyers”.

Others were more serious, and Queen’s Counsel who defended me described the proceedings as “a campaign of calumny”. Following the report, Parliament passed a law imposing “civic disabilities” on me for a period of seven years. A few months later, Mrs. Bandaranaike and another former minister (the brother of “Dias” on Jurisprudence) were each subjected to the same inquiry and the same penalty. It was a clever move by the new government to “eliminate” its political opponents, although why I was singled out for this dubious honour, I have yet to ascertain.

I returned to London in 1979 and resumed work on my research project at the School of Oriental and African Studies. Part of my research was incorporated in Paul Sieghart’s book on The International Law of Human Rights. The rest formed my thesis on “Human Rights: The Sri Lankan Experience, 1947-81”, for which the University of London awarded a PhD. My stay in London until the end of 1983, in the peaceful anonymity of academic life, was a most rewarding experience. It revived my interest in the study of law.

My first three months in London was spent in the home of an English judge, and there I had the pleasure of meeting two distinguished “men of the law”: Lord Denning and Sir Rupert Cross. I had several opportunities to undertake research into a variety of subjects, such as Commonwealth Constitutions and the Rights of Scientists, as well as the opportunity to work on the legal staff of the Commonwealth Secretariat, editing the Commonwealth Law Bulletin. The facilities for research in London, particularly at the Institute of Advanced Legal Studies, were extraordinarily rich; and some of the law teachers at the University of London were the finest I had ever encountered.

1984 saw me back in Colombo as Associate Director of the Marga Institute (the Sri Lanka Centre for Development Studies), a non-governmental, multi-disciplinary research institute, whose law division I headed. The atmosphere in the country, and at the Bar where I resumed practice, was now quite different from what it had been in the late 1970s, with the government rapidly losing its popularity. And then in July, while on a mission to Geneva, I received a telex from HKU offering me an appointment in the law faculty. I had entirely forgotten about my application submitted in the previous year from London, and which had until then evoked only a formal acknowledgment. We were finally settled in our home; my wife had resumed her work at the university; and our two daughters were back in their old school.

But the lure of Hong Kong was perhaps too difficult to resist. I had been there several times as a tourist in transit and found the territory an interesting blend of the east and the west. The Joint Declaration had just been signed and, from a constitutional lawyer’s perspective, the next decade would potentially be most stimulating. And, I was presented with an opportunity to do something which I had never wanted to do, and which I had never done before. It was an exciting, challenging prospect in a new field of endeavour. So here I am, having made a new beginning on April Fool’s Day 1985.