The Budget 2025: A Methodological Error Can Create Serious Problems

By Hema Senanayake –

Hema Senanayake

This year’s budget is crucial. By adjusting the budget or preparing the budget the government can manage economic stability, control inflation, reduce unemployment, ensure debt sustainability and promote sustainable growth, making it a crucial part of fiscal policy.

Therefore, after submitting the budget what is written elsewhere specially in the NPP’s election manifesto in regard to the fiscal policy, directly or indirectly has economically no relevance for argument. In analyzing the budget, however if any parliamentarian or economist need a reference document to compare with then the best document Is the IMF’s review report published in June 2024, because considering the debt sustainability and putting the economy back on growth trajectory Sri Lanka’s monetary authorities have basically agreed what should be the budget 2025 look like.

Superficially, it seems that the government has taken extra care to fulfill the expectation of IMF’s main criteria but has significantly deviated with some expectations and principles, possibly due to methodological errors of the budget preparation.

Two key parameters of the IMF report are Primary Balance and the Revenue to GDP ratio. The IMF insisted that the primary balance should be 2.3% of GDP and Revenue to GDP ratio must be 15.1% of GDP in 2025. In the budget the government has achieved these targets. Hence, the government’s concern to go with the IMF’s targets is commendable.

The problem is while achieving these targets the government has deviated in regard to absolute figures that ensure debt sustainability. These parameters are Overall Balance or budget deficit and financing of the same. The IMF’s expectation is to reduce the overall balance or budget deficit while achieving the required primary balance. This is a key principle in ensuring debt sustainability and this budget has ignored this principle. This means that the primary balance is a relative target, achieving this target has no meaning if the overall balance is increased on a continuing basis. The IMF might call, let us say, an explanation on this point.

How the government highly concerned with the IMF’s fiscal policy targets miss such an important principle. I would say it could be a methodological error.

Let me explain it briefly. Backward calculation could be the culprit.

There are a few known parameters or variables in preparing the budget. Revenue is known, Primary balance is fixed by IMF, interest payment is known, and GDP has been estimated. Total expenditure is still unknown. Then anybody can calculate the total expenditure by using the equation to calculate primary balance. Primary balance is the revenue surplus after deducting expenditure excluding interest and when the answer is divided by GDP and multiplied by hundred, we will get it as a ratio. The IMF wants this ratio to be 2.3% in 2025.

Therefore, the equation of calculating primary balance can be written as follows.

Primary Balance = [Total Revenue – (Total Expenditure – Interest)/ GDP] * 100

In the above equation the unknown parameter is the total expenditure. So, you may calculate what the total expenditure should be while achieving the primary balance of 2.3% by doing this backward calculation. The figure for total expenditure so calculated arrived at 7, 190 billion rupees. With these figures we have achieved primary balance of 2.3% and Revenue to GDP ratio of 15.1% but overall budget negative balance (deficit) increased by 419 billion rupees than the IMF target. A widening deficit means that the government is spending significantly more than it is earning. Total expenditure has increased by 292 billion rupees or 1.5% of GDP, compared with IMF’s targets. Overall impact of these figures requires the government to increase domestic borrowing by over 904 billion rupees than estimated by the IMF for the year 2025. This is a staggering amount. This will badly affect debt sustainability. Also, this means that the government is to borrow enormous amounts of money to finance its tax concessions, salary/wage increases, various subsidy increases and for increased capital expenditures. Once the total expenditure is matched to the primary balance of 2.3% of GDP, this mistake which can negatively affect debt sustainability, cannot be avoided.

However, the government intends to increase the demand ensuring growth by putting more money in people’s wallet, which can in turn tend to increase the private credit growth. If this happens it is certain that there will be a negative impact on the national current account which could contribute to destabilizing the rupee. This means the government and the central bank must contain private credit growth proactively. I hope that constructive criticisms are welcomed by the government.

Manorani Anta; It was all there in that smile!

The writer opines that the film ‘Rani’ has tried to pass off an uninspired, uncharacteristic portrait of a true icon as a work of art and a piece of cultural history. And in doing so, it does a disservice to her memory

- Let me say what mattered most to Manorani was Richard of course

- Manorani was never alone. She was always—even after Richard’s death—surrounded by people who loved her, even idolised her

- When Richard was killed, her world collapsed. We saw it. We watched it happen

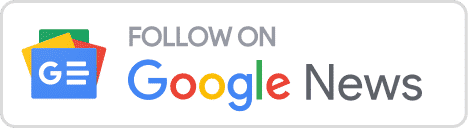

When I close my eyes I can picture Manorani. She wore jasmines in her hair, and classically Sri Lankan sarees, never Indian ones, those Nylex, floral print sarees that draped so gracefully on her tall frame. She always wore a powdered pottu. If she didn’t have time for the powder, she would smear it on with lipstick. She never carried a doctor’s bag, but she always had a stethoscope slung over her shoulder. She never kept alcohol in the house. Nor did Richard, for that matter. Their home was not that kind of place. It was the place they returned to, after work, after socializing, even after drinking! A place to read and write and rest.

When I close my eyes I can picture both Manoranis, the Manorani before Richard’s murder and the Manorani after. She never really smiled the same way again, but she retained all of her strength, all of her purpose, and all of her dignity. It is a shame that we see none of that—none of her—in this film

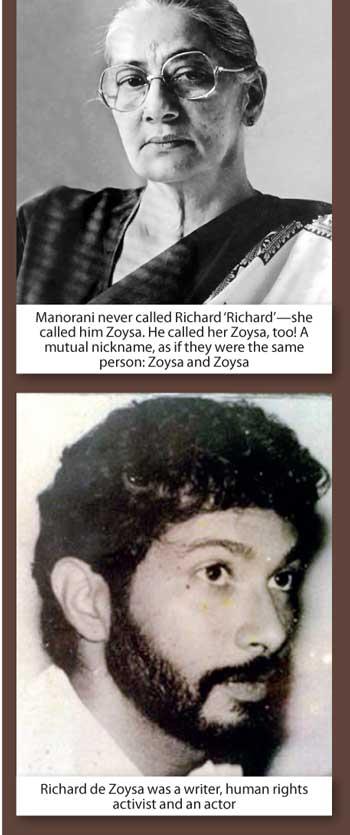

Manorani never called Richard ‘Richard’—she called him Zoysa. He called her Zoysa, too! A mutual nickname, as if they were the same person: Zoysa and Zoysa. But they never hugged. She never hugged any of us, actually. With Manorani it was always her smile. That was how she conveyed her warmth and affection for us, her love. It was all there in that smile.

Manorani never called Richard ‘Richard’—she called him Zoysa. He called her Zoysa, too! A mutual nickname, as if they were the same person: Zoysa and Zoysa. But they never hugged. She never hugged any of us, actually. With Manorani it was always her smile. That was how she conveyed her warmth and affection for us, her love. It was all there in that smile.

Manorani Anta. That’s how she was known to us. Known to me, at least, and she has been a part of my life practically since my birth. She was one of the most dignified, most courageous woman I have known. She spoke with authority but never crudely. In her medical practice she was not just our beloved family doctor, she was the classic, the quintessential no-nonsense family doctor: sensible, practical, calm. She delivered both my daughters. She delivered the babies of a generation of women. In so many ways, she was an icon for a generation of women. For those of us who knew her intimately as well as for so many others who only glimpsed her from a distance, aspiring female medical students who would see her riding her bicycle to and from campus, and then later, all the hundreds of mothers across Sri Lanka for whom she represented a light in utter darkness. But I’m jumping ahead. Before I speak about how and why Manorani mattered so much to us—and why her memory matters to so many—let me say what mattered most to Manorani.

Zoysa, of course. Her life revolved around her work, and around him. Her relationship with him reflected her best qualities. It was a deeply intellectual relationship, nurtured in the head and stored in the heart. What they shared was not overly public. It was a very private bond, but because of the kinds of people they were, they drew scores of people to them and around them. In that sense, Manorani was never alone. She was always—even after Richard’s death—surrounded by people who loved her, even idolized her.

When Richard was killed, her world collapsed. We saw it. We watched it happen. Yet, in a way, Manorani’s core remained the same. She never descended into drink, or foul language, or anger. Even when she confronted his killers, she did so with tremendous grace and dignity.

A time of unspeakable trauma

The days following Richard’s murder was a time of unspeakable trauma, with new horrors surfacing every minute. We all lived in intense fear. We feared for our lives and the lives of our children, even sending them away to live with relatives elsewhere. We feared sleeping in our own home. It was at this time that Manorani developed a defiance we might not have expected, and it started with Zoysa’s funeral. Our family had always cremated or buried our dead. Manorani ordered a public pyre to be built. It was terrifying, spectacular. Cinematic. Any filmmaker would kill to replicate such a scene.

Then came the anti-climax. After the terror and grief, after all the press and the performances and the public outcry, then came the rest of her life. She did not embark on it as a political journey but in the same spirit of her relationship with Zoysa—as a deeply personal, almost private journey. As a mother.

Every month I accompanied her to a small village off Maho, where she worked with women who had lost their husbands during the reign of terror. Every single man in that village had been taken by the police and never seen again. Though it was the men who had been disappeared, Manorani called it the village of Lost Women, because at the time they were completely unable to fend for themselves in the absence of the breadwinners in their families. So they would come to the local temple grounds, and I would play games with the little ones while Manorani convinced the women to find ways to restart their lives. It was an uphill task, but she did it and they slowly started small businesses of their own and began to stand on their own two feet. They used to say, about her, “She’s like a goddess to us.”

To this day, there is only one small newspaper article about her work in this village. That’s because it was not politically motivated, or glamorous in any way. It was less about standing behind a banner of the Mother’s Front and more about her determination to uplift women with whom she felt a true kinship—women who had suffered a tragedy just like hers under that regime.

When I close my eyes I can picture both Manoranis, the Manorani before Richard’s murder and the Manorani after. She never really smiled the same way again, but she retained all of her strength, all of her purpose, and all of her dignity. It is a shame that we see none of that—none of her—in this film. Worse than a shame; it’s a devastating and disrespectful misrepresentation of a tremendous woman. And, strangely, a woman who was always larger than life, who was almost made for the big screen.

Although it was painful for those of us who knew her to sit through that film, we can at least find some comfort in our memories of the real Manorani. Those are unshakeable for us. The real tragedy is what this film has done for an entirely new generation—it has tried to pass off an uninspired, uncharacteristic portrait of a true icon as a work of art and a piece of cultural history. And in doing so, it does a disservice to her memory. She deserved better than this.

(Marie-Helene D’Almeida is the niece of Manorani Saravanamuttu. She is a retired teacher of Art, Drama and English)