How and Why the Banda-Chelva Pact was Signed by Bandaranaike and Chelvanayagam

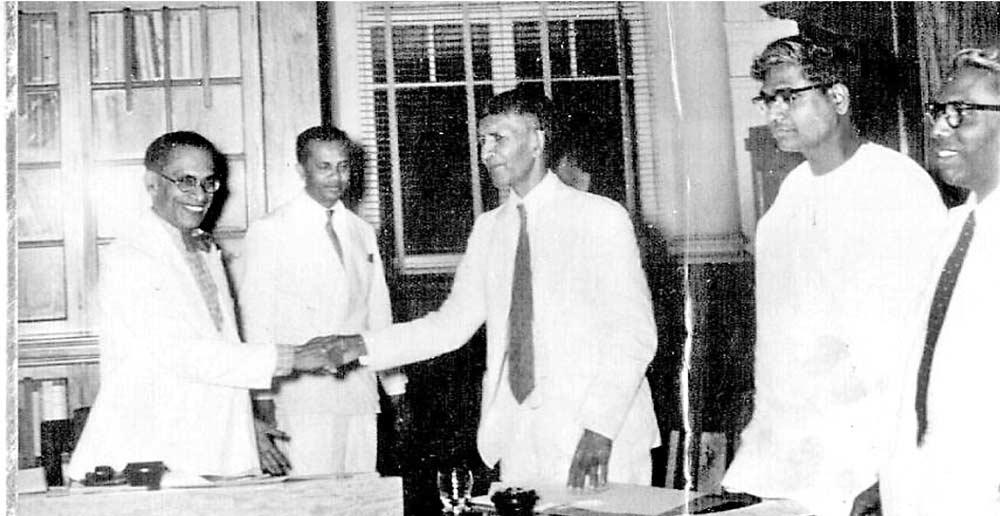

PM Bandaranaike and FP leader Chelvanayagam

Today, the 26th of April, is the 48th death anniversary of respected Tamil political leader Samuel James Veluppillai (SJV) Chelvanayagam. Chelvanayagam known as SJV and Chelva was the co-founder and long time leader of the Ilankai Thamil Arasuk Katchi (ITAK) known in English as the Federal Party (FP). The ITAK/FP launched in December 1949 is currently celebrating its diamond jubilee year. The ITAK/FP is regarded as the premier political party of the Sri Lankan Tamils in the Northern and eastern provinces of Sri Lanka.

SJV Chelvanayagam spearheaded Tamil political resistance to perceived Sinhala majoritarian hegemony for many years. He adopted an agitation cum negotiation strategy in his political approach. The ITAK/FP engaged in several non-Violent protest campaigns while opting to negotiate with the governments in power whenever the time was opportune.

SJV Chelvanayagam spearheaded Tamil political resistance to perceived Sinhala majoritarian hegemony for many years. He adopted an agitation cum negotiation strategy in his political approach. The ITAK/FP engaged in several non-Violent protest campaigns while opting to negotiate with the governments in power whenever the time was opportune.

Among the many attempts by the Chelvanayagam -led ITAK to resolve the prickly Tamil national question was the signing of an agreement known generally as the Banda-Chelva pact or B-C pact. This was an agreement based on power sharing principles between the then Prime minister Solomon West Ridgeway Dias Bandaranaike and Chelvanayagam. It was a historic pact possessing great potential. Unfortunately The B-C pact was Not allowed to work and was short-lived. It is against this backdrop that this column — with the aid of previous writings – focuses this week on how and why the Banda- Chelva pact was signed 68 years ago.

Deep Polarisation

The historic 1956 General elections brought about a deep polarisation between the Sinhala and Tamil communities. The Mahajana Eksath Peramuna joint front headed by Sri Lanka Freedom Party (SLFP) leader S.W.R.D. Bandaranaike swept the polls in the Seven Sinhala majority southern provinces. The Ilankai Thamil Arasuk Katchi(ITAK) known in English as the Federal Party(FP) led by S.J.V. Chelvanayagam won six out of nine seats in the northern Province and four out of seven in the eastern Province.

One of the first acts by the new government was the enshrining of Sinhala as the sole official language of the country. On June 5 1956, ,Tamil Satyagrahis peacefully protesting at Galle Face were beaten up by thugs as the police did nothing to stop it. Anti-Tamil violence erupted in several parts of the country. On June 15, Sinhala was made the only official language by a vote of 56 to 29.

There was much tension in the country when the ITAK/FP held its party convention in Trincomalee from August 17-19, 1956. The ITAK/FP convention passed a unanimous resolution incorporating four basic demands. They were –

- The establishment of an autonomous Tamil state or states on a linguistic basis within a Federal Union of Ceylon.

- The restoration of the Tamil language to its rightful place, enjoying absolute parity of status with Sinhala as an official language of this country.

- The restoration of the citizenship and franchise rights to the Tamil workers in the plantation districts by repeal of the present citizenship laws.

- The immediate cessation of all policies of colonising the traditionally Tamil-speaking areas with Sinhalese people.

The convention resolved that one year be given the government to respond positively to these demands. If there was no response the ITAK was to commence a ‘direct action’ campaign of non-violent protest. The deadline given was August 20, 1957.

The year 1957 dawned with much friction over the issue of the ‘Sri’ letter in vehicle number plates. The earlier system was to use English alphabet letters from the country’s name CEYLON (CE, CL, CN, EY, EN etc). Now the new government wanted to replace that with the Sinhala ‘Sri.’ The Tamil politicians resented this as a form of Sinhala imposition. They protested and demanded that the Tamil ‘Shree’ also be substituted. Ironically there was no letter ‘Shree’ in the Tamil alphabet. The ‘Shree’ used was derived from Sanskrit.

Anti-Sri Campaign

On January 19 the ITAK/ FP began an anti-Sri campaign in the northeast. Vehicles began running with Tamil letters. The ‘Sinhala’ Sri was changed into the Sanskrit derived ‘Tamil’ Shree. On February 4 the ITAK/FP observed Independence Day as a ‘black day’ of mourning. A hartal paralysed normal life in the northeast. Nadarajah, a volunteer in Trincomalee was shot dead when climbing the clock tower to tie a black flag.

A counter-campaign began in the Sinhala majority provinces. Tamil letters were tar-brushed or blacked out on street signs and name boards. There were widespread incidents of communal friction on a minor scale. The ITAK/ FP also called for a boycott of government ministers and deputy ministers visiting the northeast for ‘official’ purposes. Satyagrahis would converge at places where ministers were scheduled to go and curtail their movement.

With increasing communal tension, the country seemed to be heading for a blood bath. S.W.R.D. who was arguably the most intellectual of all Sri Lanka’s prime ministers realised that the situation had to be checked and reversed. He understood that the Tamils had genuine grievances that had to be redressed. Bandaranaike, the man who espoused federalism for Sri Lanka in 1926 knew that effective power sharing was the only solution. He now proposed extensive de-centralisation through the setting up of Regional Councils.

It is widely believed that the Regional Councils scheme was introduced by Bandaranaike as a result of the Banda-Chelva pact. Actually, a draft bill for Regional Councils was published on May 17, 1957. The B-C pact came later in July. After presenting the Regional Councils Bill, S.W.R.D. wanted to arrive at an understanding with the Tamil leaders and modify it further.

Meeting Mooted

Meanwhile ITAK was getting ready for its ‘direct action’ campaign scheduled to begin on August 20. Volunteers numbering 25, 000 were registered. Some Sinhala leaders began a move to mobilise 100, 000 volunteers to combat the Tamil campaign. A major showdown seemed inevitable. It was then that saner counsel prevailed. A meeting between S.W.R.D. and S.J.V. was mooted. It was done on the personal initiative of the Prime Minister himself.

Two Tamil lawyers, P. Navaratnarajah QC and A.C. Nadarajah arranged for the rendezvous. Navaratnarajah was a personal friend of both S.W.R.D. and S.J.V. Nadarajah was a vice-president of the SLFP. From the government side the then Finance Minister Stanley de Zoysa played a commendable role in promoting this dialogue.

One of the first acts by the new government was the enshrining of Sinhala as the sole official language of the country. On June 5 1956, ,Tamil Satyagrahis peacefully protesting at Galle Face were beaten up by thugs as the police did nothing to stop it. Anti-Tamil violence erupted in several parts of the country. On June 15, Sinhala was made the only official language by a vote of 56 to 29

One of the first acts by the new government was the enshrining of Sinhala as the sole official language of the country. On June 5 1956, ,Tamil Satyagrahis peacefully protesting at Galle Face were beaten up by thugs as the police did nothing to stop it. Anti-Tamil violence erupted in several parts of the country. On June 15, Sinhala was made the only official language by a vote of 56 to 29

First Meeting

The first meeting was held on June 22 1957 at the Premier’s residence in Horagolla. S.W.R.D. himself came up to Chelvanayagam’s car and helped him get out. Both men seemed to realise the gravity of the situation. Those present on this historic occasion were S.W.R.D. Bandaranaike and Stanley de Zoysa from the government; Navaratnarajah as an intermediary; S.J.V. Chelvanayagam, C. Vanniyasingham, N.R. Rajavarothayam, V.A. Kandiah, E.M.V. Naganathan and V. Navaratnam from the ITAK/FP.

The first meeting was held in a cordial atmosphere. S.W.R.D. tried to downplay Tamil fears by saying that it would take many years for Sinhala to become the official language in practice. The FP appreciated Bandaranaike’s position but insisted that provisionary arrangements on the status of Tamil will have to be made. S.W.R.D. concurred.

When the question of power sharing arose the ITAK presented its case for a federal state. The ITAK pointed out that S.W.R.D’s own viewpoint in 1926 that federalism was the ideal solution had been a source of inspiration for the party in demanding federalism. S.W.R.D. replied by saying that though he espoused federalism then, he had subsequently changed his mind. Besides, SWRD said he had no mandate for introducing federalism. “Could not the FP think of an alternative solution short of federalism that would redress Tamil grievances and address aspirations?” he queried. The ITAK/FP understood the Prime Minister’s situation and agreed not to press for a federal solution.

The PM then suggested that the FP should come up with alternative proposals envisaging ‘massive de-centralisation’ but not ‘federal autonomy.’ The ITAK/FP agreed and departed. The FP consulted former Law College Principal Brito Muthunayagam and Alfred Jeyaratnam Wilson, the son-in-law of Chelvanayagam. Wilson, then a university lecturer, went on to become dean of political science at the Universities of Peradeniya and New Brunswick in Canada.

Northern Ireland

Interestingly, Brito Muthunayagam felt that the status of Northern Ireland in Britain was the ideal model to follow. The Northern Ireland parliament was subordinate to the British parliament but retained a lot of powers not amounting to federalism.

The FP was given a copy of the Northern Ireland Constitutional Act by the Law College principal. Wilson provided copies of the constitution of several federal countries. Kopay MP. C. Vanniyasingham and ITAK secretary V. Navaratnam set about drafting an alternative scheme. The FP leaders accomplished the task in three days and forwarded the draft through Navaratnarajah for S.W.R.D’s perusal. The Ulster model influenced the draft greatly.

The northeast was to be a subordinate state with a unicameral legislature and cabinet. External affairs, defence, currency, stamps, customs, inter-regional transport, but would remain with the central government. Block grants would be made by Colombo while domestic taxation could also supplement revenue. Policing was a state responsibility. The subordinate state would be represented in Colombo through elected MPs. There would be a central cabinet minister for Tamil affairs.

Second Round of Talks

The second round of talks was at S.W.R.D’s Rosemead Place residence. Chelvanayagam, Vanniyasingham, Naganathan and Navaratnam represented the ITAK/FP. Bandaranaike pointed out that the proposals in essence amounted to federalism. He suggested that the scheme be whittled down in point form to emphasise administrative de-centralisation. He also objected to words like ‘parliament’ and ‘cabinet’ saying they smacked of a separate state.

ITAK then returned and revised the document by summarising proposals in point form. Since the Regional Council concept was a brainchild of Bandaranaike, ITAK replaced ‘parliament’ with ‘regional council’. ‘cabinet’ was substituted by ‘board of directors’. The substance of the original proposals was retained to a great extent. Thereafter a series of discussions took place among Stanley de Zoysa, Navaratnarajah and FP leaders. The PM did not participate but proposed many changes through his representative Stanley de Zoysa.

At 2.30 a.m the members of the fourth estate, waiting eagerly for a sensational breakthrough, were called in to the cabinet room. Amid flashing cameras Bandaranaike apologised in his courteous manner: “My friends, I am sorry to have kept all of you awake. But it is a historic night for you, for us and for the country

At 2.30 a.m the members of the fourth estate, waiting eagerly for a sensational breakthrough, were called in to the cabinet room. Amid flashing cameras Bandaranaike apologised in his courteous manner: “My friends, I am sorry to have kept all of you awake. But it is a historic night for you, for us and for the country

ITAK/FP was persuaded to accept most of them though they diluted to some extent the original proposals. But on one point the ITAK remained firm. ITAK wanted the northeast to form one single regional council. S.W.R.D. was willing to allow the north to be one unit but he wanted the east to be separate with two or more units. The man who was adamant on this issue was FP strategist V. Navaratnam dubbed as the ‘golden brain’ of ITAK. Finally A.C. Nadarajah persuaded Navaratnam to accept a compromise. The north and east were to be separate councils with the provision to amalmagate if they so desired.

Conclusive Meeting on July 25 -26

The conclusive final meeting took place on July 25, 1957 at the Prime Minister’s office in the old Senate building. Several cabinet ministers were in attendance. Many ITAK/FP leaders also participated. Navaratnarajah the ‘facilitator’ was also there. The talks began at 7 p.m.The cabinet ministers were firm that the status of Sinhala as official language should not be eroded. After protracted discussion a compromise was suggested by William Silva that Tamil be recognised as the language of the national minorities. Tamil was to be the language of administration in the N-E. On the unit issue the FP consented to the premier’s stance that the north be one council and the east be divided into two or more councils. The councils could merge if desired even cutting across provincial boundaries. Existing boundaries could be re-demarcated if necessary.

When it came to powers of the council several ministers led by Philip Gunewardena refused to delegate their powers. The Tamil party members retired to another room while cabinet ministers sorted out the issue. Subsequently ‘line’ ministers agreed to devolve their powers.

The PM was willing to stop colonisation and also agreed to land settlement procedures satisfactory to the ITAK/FP. On the question of citizenship Bandaranaike stated that he would resolve the issue through discussions with plantation Tamil representatives. He suggested the FP should “leave it at that.” The party complied. It was well past midnight now and July 26 1957 had dawned. At 2 a.m on July 26, V. Navaratnam read out in point form the agreement reached. Both sides formally agreed. At 2.30 a.m the members of the fourth estate, waiting eagerly for a sensational breakthrough, were called in to the cabinet room. Amid flashing cameras Bandaranaike apologised in his courteous manner: “My friends, I am sorry to have kept all of you awake. But it is a historic night for you, for us and for the country.”

“We have reached an agreement.”

Ranji Handy was then a Lake House journalist. The irrepressible Ranji who became Mrs. Maithripala Senanayake in later life blurted out: “Tell us the result please.”Then Stanley de Zoysa announced “We have reached an agreement.”

S.W.R.D. then turned to S.J.V. and said “Chelva, they want to hear from you.” Chelvanayagam said an agreement had been worked out and that the details will be given by the Prime Minister. Bandaranaike then asked the press whether there was time to catch the printing deadline. Joe Segera of Lake House shouted spiritedly that special arrangements had been made to print late and wanted the full details. S.W.R.D. then read out from V. Navaratnam’s notes.

The press persons asked FP leaders whether they were satisfied. Naganathan, Vanniyasingham, Rajavarothayam and Amirthalingam replied in the affirmative. Chelvanayakam then stated that the ITAK would postpone its ‘direct action’ campaign scheduled for August 20. The press rushed out and the morning papers came out later than usual with the full text of the agreement. The evening papers came out earlier than usual with more details.

No Pact was Signed

It may be hard to believe, but the funny thing was that no pact had been signed by Bandaranaike or Chelvanayagam at that point. There was no B-C pact. It was like a gentleman’s agreement.

Chelvanayagam and Navaratnam returned to the party leader’s residence at Alfred House Gardens. It was there that Navaratnam pointed out that there was nothing concrete in writing that an agreement had been entered into. There would only be media reports.

S.J.V. then suggested that Navaratnam take some rest and handle the matter in the morning. Getting up early morning, Navaratnam drafted in triplicate, the terms and clauses of what came to be known as the Banda-Chelva pact .It was in two parts. Part A – was a summary of discussions and agreements reached. Part B – was about the structure, powers and composition of the proposed Regional Councils.

Meanwhile ITAK was getting ready for its ‘direct action’ campaign scheduled to begin on August 20. Volunteers numbering 25, 000 were registered. Some Sinhala leaders began a move to mobilise 100, 000 volunteers to combat the Tamil campaign. A major showdown seemed inevitable. It was then that saner counsel prevailed. A meeting between S.W.R.D. and S.J.V. was mooted. It was done on the personal initiative of the Prime Minister himself

Meanwhile ITAK was getting ready for its ‘direct action’ campaign scheduled to begin on August 20. Volunteers numbering 25, 000 were registered. Some Sinhala leaders began a move to mobilise 100, 000 volunteers to combat the Tamil campaign. A major showdown seemed inevitable. It was then that saner counsel prevailed. A meeting between S.W.R.D. and S.J.V. was mooted. It was done on the personal initiative of the Prime Minister himself

Solomon and Samuel

Chelvanayagam then took the copies and went at noon on July 26 to the Prime Minister’s office. It was there that the old Thomians – Solomon and Samuel – endorsed the historic agreement known as the Bandaranaike-Chelvanayagam pact. It was done quietly away from media glare. Bandaranaike had one copy and Chelvanayagam the other. Navaratnam the ‘draftsman’ kept the third copy.

Years later Navaratnam told this writer in a conversation at his son Mohan’s house in Toronto, the sad tale of how that copy of the “historic document” was destroyed by EPRLF militants during the Indian Army period. It was at his residence in Jaffna which the EPRLF had taken over then.

Navaratnam, the driving force behind the B-C pact, also told me that the ITAK/FP was not happy with all aspects of the agreement but compromised in a spirit of pragmatism. The veteran Tamil leader who split from the FP in 1968 and founded the Tamil Self-Rule party passed away at the age of 97 in Montreal, Canada in 2006.

B-C Pact in Retrospect

In retrospect the B-C pact seems to have been one signed by leaders who realised that the ethnic problem had to be resolved if the nation was to realise its full potential. There was also a sense of urgency then to arrive at an understanding in order to contain the rising mood of ethnic confrontation in the country. Sadly, the pact was never implemented. There was much opposition to it.

The agreement signed by SWRD Bandaranaike and SJV Chelvanayagam in 1957 was a significant event in the political history of post-independence Sri Lanka. The Prime minister of the day and the leader of the largest Tamil political party had come to an understanding which if implemented may have helped contain the ethnic conflict at its nascent stages.

The agreement known generally as the “Banda-Chelva pact” was never allowed to work because of political opposition in the South. The opposition came from hardliners among the Sinhala Buddhist clergy and laity as well as hawkish elements among both the government and opposition.

Golden Opportunity Missed

The B-C pact was a golden opportunity to resolve the Tamil national question at its early stages through a political settlement based on power sharing principles. Yet it never worked or was allowed to work. In fact it never ever got off the ground. Tragically, the ethnic crisis deteriorated gradually into open war and the country kept bleeding for many years.

D.B.S.Jeyaraj can be reached at dbsjeyaraj@yahoo.com