FEATURES

Cathedral of Christ the King (Photo by Uthpala Wijesuriya)

By Uditha Devapriya (with Uthpala Wijesuriya)

Something always seems to compel me to return to Kurunegala. It’s a land of contrasts, contradictions, and convulsions. The heat, to be sure, can be unbearable, and in April it’s particularly so. Despite such niceties, though, I have visited it much more than any other place or region outside Colombo and the Western Province, barring Galle. Of course, there was always some rational, justifiable reason that pushed me to return to Galle and the wider South: my maternal family. Kurunegala had once been home to my paternal family, yet they had left it early on. No common ties, no familial links, bonded me there.

What, then, makes me want to return here? It’s arguably one of the most important urban centres in the country, after Colombo, Kandy, and Galle. It’s a transit point between the Western Province and the Central Province, indelibly associated with, if not linked to, Kandy. It’s also of much importance for the historian: what other region in the country can claim to have hosted four kingdoms, from four different periods?

Like most other regions, Kurunegala exists beyond the city, but is part of it too. The city has developed almost as much as Colombo has, and much more than Galle and Kandy. From one corner to another, you come across restaurants, complexes, itinerant hawkers and peddlers, and ubiquitous trishaws. The bus station, perhaps one of the biggest in the country, covers a plethora of shops and complexes selling everything, from mobile phone accessories to fruits to subwoofers and milkshakes. The main shopping complex does not quite compare with its counterparts in Colombo, Kandy, and Galle, but for what it’s worth, it’s big.

Historically, Kurunegala served as a fortress, a bulwark against invading forces. Rocky boulders adorn the region, creeping up in every corner, absorbing the intense heat. In April the heat can be particularly unbearable. The driver of the trishaw I found myself in told me pointedly that trishaw drivers never go up Ethagala, the most popular of the outcrops over here, between March and May. The heat may have helped in warding off invading forces and the rulers probably used it to their advantage. In any case, boulders and outcrops served as military strongholds here, and they succeeded in warding off outsiders.

The kingdom associated most strongly with Kurunegala, however, is neither Yapahuwa nor Dambadeniya, nor for that matter Kurunegala. The latter did not last for very long: nothing much remains from that era. When the Sinhalese kingdom shifted from the south-west to Kandy, the latter slowly absorbed Kurunegala and Sabaragamuwa, along with the Southern interior. This fuelled a revival of the arts in Kurunegala, a revival visible almost everywhere. The Ridi Viharaya, as I pointed out in my earlier article on Kurunegala, stands as the epitome of this revival. But the Ridi Viharaya is one among many, often smaller temples which trace their origins to the Yapahuwa Kingdom, if not earlier, and which underwent a revival in the Kandyan Kingdom. Naturally, among the many influences these temples have imbibed, it is the cultural and artistic motifs of Kandy that have prevailed.

It is that Kandyan influence, in fact, which seems to have motivated the Church of Ceylon to set up a separate Diocese there. In terms of the following the Church of Ceylon enjoys in these parts, it did not make sense to establish a separate Chapter here. But from a historical or geographical perspective, it made perfect sense. Kurunegala serves as a nexus between the Western Province and the Kandyan regions, and it seemed logical to absorb some if not many of the churches, cathedrals, and mission societies that had been established in the latter areas, including parts of Sabaragamuwa. The result is that while some parts of these districts today belong to Kurunegala, others belong to Colombo.

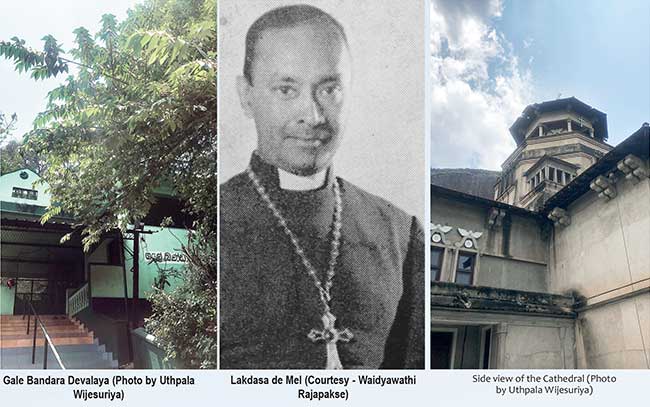

The setting up of the Kurunegala Diocese coincided with a drive towards indigenisation within the Anglican Church. This development is associated with two figures in particular: A. G. Fraser of Trinity College, and Lakdasa de Mel. De Mel’s name is inextricably linked to the Kurunegala Diocese: he was, after all, its de facto founder. Having served as Assistant Bishop of Colombo for five years, de Mel took the lead in establishing a new, separate Chapter in Kurunegala, essentially financing it with his wealth and inheritance. That coincided with his efforts at reaching out to other communities, particularly the Buddhist clergy: he made it a point, in fact, to invite the Chief Prelates of the Asgiriya and Malwatte Chapters to religious functions, including at such sites as the Trinity College Chapel.

It is easy to miss the Cathedral of Christ the King now. It juts out and is visible even from a distance, yet unless one specifically locates it, one can easily pass by it. But this is only to be expected when its very entrance evokes the motifs of the entrance to a typical Buddhist viharaya. The Cathedral, in that sense, is a fitting tribute to the Anglican Church’s efforts at indigenisation. Like the Trinity Chapel, it incorporates elements of Kandyan art, including the pattirippuwa, along with Anuradhapura and Polonnaruwa sculpture. One comes across such elements inside as well. A photo of the induction of Lakdasa de Mel’s successor, Lakshman Wickremesinghe, for instance, features that most Buddhist of desiderata, the sesath. To give another example, the fresco, which Wikipedia once attributed to George Keyt – who painted very few Christian themes – was done by a complete outsider, Stanley Kirinde.

Lakdasa De Mel came from one of the wealthiest families in Ceylon. They owned land throughout Kurunegala, and he gave it liberally to various causes. His name is not carved in stone everywhere, but a school in the city – Lakdasa de Mel College – and a whole village – Melsiripura – are named after him. De Mel also gave some land in Ibbagamuwa to Yohan Devananda. That is now Devasaranaramaya, which, in keeping with the Church of Ceylon’s philosophy at the time, assimilated Buddhist and Hindu elements.

Just a few hundred metres from the Cathedral, one comes across a different religious site: the Gale Bandara Devalaya. Officiated by a Muslim, the Devalaya seems to the layman an anachronism. But the notion that Muslims do not worship saints is wrong. it is only certain creeds that forbid such worship. Sufis permit these practices, and in Sri Lanka, despite a backlash from certain fundamentalist sects, the Sufi creed is still strong. In that sense the Devalaya is a tribute to the confluence of cultures that has defined Sri Lanka so well over the decades and centuries. Regardless of their faith, people visit it and pay their respects here, making vows and returning to fulfil them when they come true.

However, there is a somewhat dark history underlying the Shrine: the person after whom the Devalaya was originally established, Waththimi, was slain by Sinhalese nobles for the sin of being an outsider. His father, Bhuvanekabahu I, married a Muslim lady, reputedly from Aswedduma. Legend has it that he was originally named Ismail, but that on a request by his father it was changed to Waththimi Bandara.

While historical sources do not tell us what happened next, after being crowned king following his father’s death Waththimi had taken certain actions which had not been to the liking of the nobility. That may well have been on grounds of his race. The nobility hence connived to invite him to a Pirith Mandapaya on top of Ethagala, and then threw him to his death. The popular story is that those who connived in his death met a particularly bloody end, compelling locals to venerate the slain king and call him Gale Bandara. Today, visitors to the Shrine do not seem to be too aware of this background, nor of the ethnicity of the man they venerate. To them, as to most others, he remains one of us.

What can we conclude from that? Places and sites like the Gale Bandara Devalaya may be anachronistic at one level. But at another, they are in line with an identity that Sri Lanka has pursued. Kurunegala remains distinctly Buddhist. Yet as I mentioned earlier, it exists well beyond the city. By anchoring itself here, the Church of Ceylon reinforced these qualities, and in doing so it contributed much to that identity Sri Lanka may yet realise: one based not on an exclusivist framing of culture and community, but instead on an all-encompassing, tolerant, and benign reading of race and religion.

The writer is an international relations analyst, researcher, and columnist who can be reached at udakdev1@gmail.com.