-

Published

MV Shankaran, who died this week at the age of 98, was a legendary figure in the Indian circus industry.

The trapeze-artist-turned-circus-owner was popularly known as Gemini Shankaran, after the famous Gemini Circus that he established with a partner in 1951.

For decades, it was among India’s most popular circuses – thousands of people thronged to watch its acrobats, clowns and menagerie of animals across the country.

Its big and bright logo – often hand-painted and sometimes in neon – would bring smiles to people’s faces in India’s smaller towns and villages for decades. A ticket for a Gemini show was highly sought after in most corners of the country.

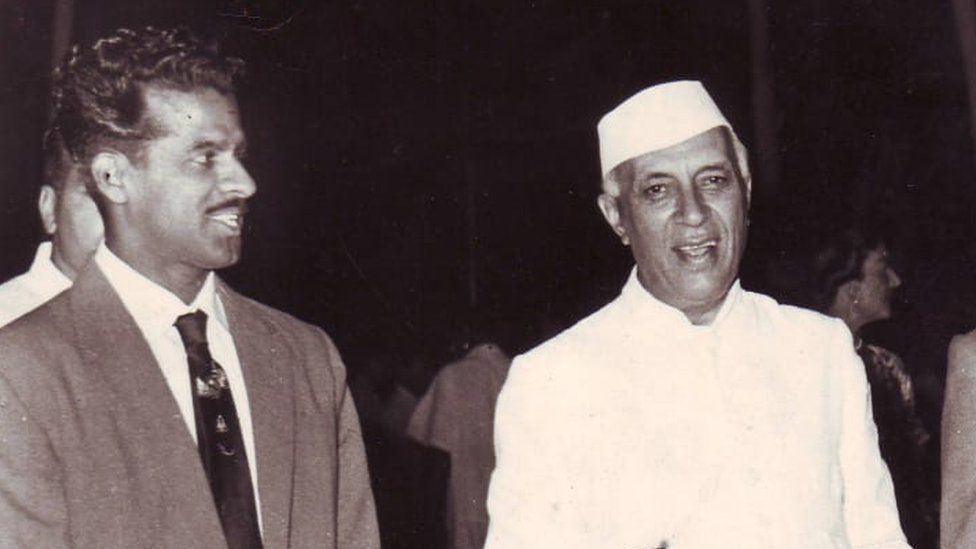

They were also in demand abroad. In the 1960s, India’s prime minister Jawaharlal Nehru sent Shankaran and a team of his performers to represent India at an international festival in the USSR. The team was given an official reception at Nehru’s residence before they left India. When they reached Moscow, Valentina Tereshkova, the first woman in space, came to greet them.

Years later, Shankaran recalled in interviews the thunderous applause their shows got in countries such as the Soviet Union and Zambia. Fans of the circus ranged from Nehru to Zambia’s first president Kenneth Kaunda. Shankaran also had albums with photographs of himself with US civil rights icon Martin Luther King Jr and several other leaders.

Over Shankaran’s lifetime, he saw both the glory days and difficult times of the circus industry.

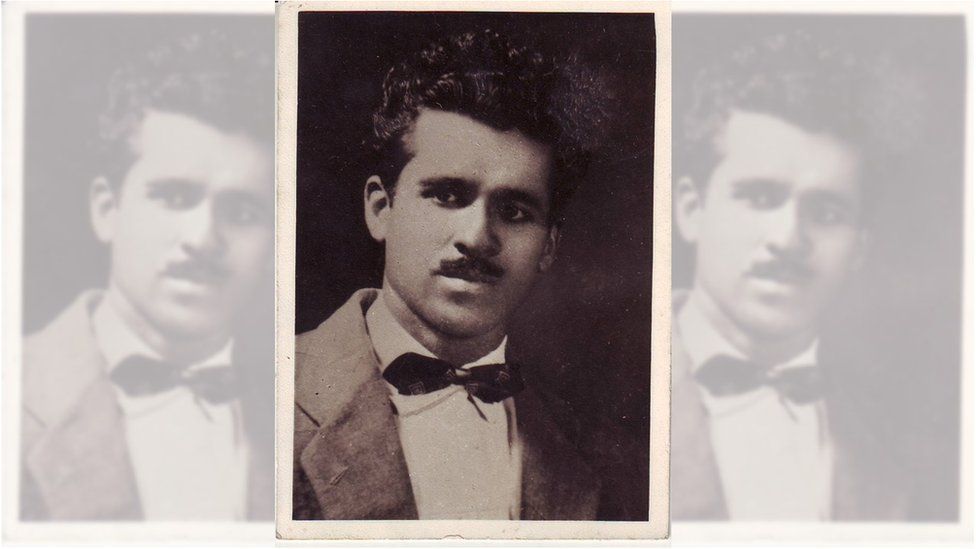

Shankaran was born in 1924 in Thalassery town in Kannur district in the southern state of Kerala. When he was around nine or 10 years old, he was fascinated by a circus performance given by a man called Kittunni (he didn’t use a surname).

Kittunni did everything himself, from announcing his own feats and selling tickets to performing stunts.

When Kittunni finished his performance and walked away, Shankaran was among a group of children who trailed behind him, says journalist Thaha Madayi, who co-wrote the circus owner’s Malayalam-language memoir Malakkam Mariyunna Jeevitham (When life does a somersault).

Thalassery was the hometown of Keeleri Kunhikannan, a gymnastics teacher who trained “countless” circus performers. Young Shankaran got permission from his school-teacher father to begin training with Kunhikannan.

But he didn’t join a circus immediately. He first opened a grocery shop, which later shut down, and then joined the army. He was posted in Calcutta (now Kolkata) as a wireless operator during World War Two.

After the war, he returned to Kerala and restarted his training under another teacher (Kunhikannan had died by then). In 1948, Shankaran joined a circus in Calcutta as a trapeze artist.

Three years later, he and a partner bought a small circus called Vijaya, which only had one elephant and two lions at the time. They renamed it Gemini, and its first performance was on 15 August 1951 in the western state of Gujarat.

Gemini soon became a phenomenon. Shankaran said in interviews that the troupe – which had hundreds of people and several animals including lions and elephants – travelled for performances in special trains.

Mr Madayi says that Shankaran was inspired by the iconic Ringling Brothers circus in the US.

“He dreamt of reaching the high standards set by international circuses. While there were many limitations, he did manage to bring in many innovations and modernised his circuses,” he says.

Several prominent Indian politicians – including former prime ministers – and celebrities came to watch the performances by Gemini and Jumbo (another big circus set up by him in 1977) artists. Many scenes from the 1970 Hindi classic film Mera Naam Joker and the 1989 Tamil hit Apoorva Sagodharargal were shot at the Gemini Circus.

Though Shankaran had a remarkably action-packed life, Mr Madayi says he was struck by his humility when they first met.

“We met at a book release function, where he came and introduced himself to me. Though he had lived such an exciting life, he spoke less about himself and more about others in the circus industry,” he recalls.

It’s an impression shared by academic Nisha PR, who has worked extensively on the social history of the Indian circus. When she interviewed Shankaran for her research, he was “full of stories, gentle and approachable”, she told the BBC in an email.

Shankaran’s reluctance to speak about himself, however, made Mr Madayi’s job of documenting his memories difficult, the journalist recalls.

“His answers were sparse and brief. I had to ask him many questions over several sessions to elicit details from him,” he laughs.

Shankaran was insistent that the book should be as interesting as a circus performance.

“He would say that the chapters should be brief, that one should move on to the next ‘item’ without giving the reader a chance to yawn,” Mr Madayi says.

In his final years, Shankaran – whose sons manage Gemini and Jumbo now – was both hopeful and concerned about the future of Indian circus.

“Circus was like oxygen for him,” Mr Madayi says. “He did not look at it as a means to earn a living, but as a reason to live.”

With his death, a great chapter in India’s glorious circus history has ended.

Circuses have struggled to thrive in recent years.

“With the advent of TV and cinema, people have many more things to watch, so they’ve stopped going to the circus. Also, India has banned some wild animals from being trained as performing animals. The younger generation doesn’t want to work in the circus. How long can the old generation perform?” says Mahendra Dhotre, whose grandfather Damoo was one of the greatest circus performers in the world.

But those who knew Shankaran say that his legacy has enough lessons for circuses and performers to stay relevant and reinvent themselves.

And that’s something he always hoped that the new generation would do.

Additional reporting by Cherylann Mollan in Mumbai

BBC News India is now on YouTube. Click here to subscribe and watch our documentaries, explainers and features.

Read more India stories from the BBC: